Book Review: Yves Bonnefoy’s Meditation on Poetry — Heady But Essential

Yves Bonnefoy’s book is, fundamentally, a spiritual autobiography; yet it draws extensively on the outside world and ponders how it can be described in writing or depicted in painting.

The Arrière-pays by Yves Bonnefoy. Translated by Stephen Romer. Seagull Books, 234 pp., $25.

By John Taylor

Two books stand out as essential sources of the deepest and most distinctive poetics that have emerged in post-war French poetry. The first is Philippe Jaccottet’s La Promenade sous les arbres, the first edition of which goes back to 1957; the second is Yves Bonnefoy’s L’Arrière-pays (1972), just released by Seagull Books in a superbly clear and fluid English translation by the poet Stephen Romer. Romer actually produced this translation several years ago, but legal obstacles involving international copyright that were quite stingily maintained by the publishers (Albert Skira) of the original edition had kept this English and other foreign versions from appearing. In his preface, written especially for this translation, Bonnefoy tells this strange story of translation rights. For lovers of French literature, this book, which reproduces the fascinating, original illustrations as well, has been long and eagerly awaited.

Does much writing stem from, or try to resolve, an impossibility? While studying these two books, one ponders this question. The poetic and philosophical goal formulated in both books involves a seeming contradiction in terms or at least an unattainable goal. And yet it is from this contradiction or unattainable goal that emerges the poetry and poetic prose—there is no firm border between the two genres for Bonnefoy and Jaccottet—produced by these two major poets, respectively born in 1923 and 1925.

To simplify matters, Bonnefoy and Jaccottet emphasize groping for a kind of “presence”—to use the former poet’s term—that is elusive and remains out of reach by its very nature; or, to speak more like Jaccottet, the poets seek to spot “glimmers” of something perhaps transcending the here and now, the strictly material world of things. Although there are differences in style and sensibility between Bonnefoy and Jaccottet (with the latter perhaps more intently focused on death, although the former likewise bases his life-philosophy on the certitude of man’s “finitude”), it can already be observed that these “glimmers,” which for Jaccottet ultimately turn out to be merely “alluring” and remain “beyond the threshold,” are somewhat analogous to the image of the inaccessible “hinterland,” “back country,” or “arrière-pays” evoked in the title of Bonnefoy’s book.

In other words, the quest of both poets is endless; even, strictly speaking, hopeless. Yet in contrast to several other contemporaries, neither of them ends up abandoning all hopes or adopting a viewpoint whereby meaning itself is relative or even an arbitrary construct. (Some of Bonnefoy’s criticism has been aimed at this issue of post-structuralist philosophy.) In The Arrière-Pays, the poet states bluntly: “The earth is, and the word presence has a meaning.” The book approaches this hypothesis from a variety of angles.

In a sense, the experience of “presence” results from the very groping for the being of the earth and the meaning of presence, and thus sometimes from writing as a form of groping; this is especially perceptible in the at once meandering and in-spiraling style of The Arrière-pays and in the poetic prose texts, with their ever finer analyses of illusion and self-delusion, that Jaccottet has produced since the 1990s. But this groping must not be too consciously, logically, systematically, and “literarily” applied. The poet must also remain circumspect about the deceiving lures of aesthetic or stylistic “beauty”; otherwise, the possibility of sensing “presence” or glimpsing a transcendent gleam or two will vanish. “Presence,” which seems to be a concept, must therefore not be apperceived, contemplated, or analyzed as one, for something quite different from rational thinking must also be brought to bear on this search.

Not surprisingly, the poetics formulated by Jaccottet and especially by Bonnefoy are aimed at dismantling a conceptual view of Nature and its natural elements, as well as a conceptual understanding of “presence”; both men are as suspicious of rationality for rationality’s sake as of Romantic yearning. And yet, one sees how this kind of poetic thinking and practice has evolved directly from—even when it turns against—European Romanticism. Similarly, one sees how much both men have been informed by modern European philosophy, albeit as mediated by poets who particularly embody its essential issues; for Bonnefoy, this usually means Rimbaud, Baudelaire, and Mallarmé; for Jaccottet, Rilke and Hölderlin. Both Bonnefoy and Jaccottet are definitely thinking poets, though with great love and respect for the empirical facts of existence.

If all this sounds heady, it is. Although the simplest elements of Nature are evoked time and again concretely, even sensually, they are presented in such a way that this philosophical questioning is also always implicit (and often explicit). To grasp these poetics more clearly, let us return to this fundamental notion of hope. The writing of both men can be defined as an attempt, via poetry or poetic prose, to question rigorously yet perhaps nonetheless found the possibility—however slight—of hope. At stake is “how to live.” In the process, both poets constantly turn their skepticism not only against false appearances and false hopes but also and especially against themselves, notably their own aspirations for transcendence, conceptual clarity, and spiritual faith in its most general sense. If they are attentive to “epiphanies”—to cite a term perhaps more familiar than “presence” to Anglo-American poetry readers—both Bonnefoy and Jaccottet are wary of allurements that might turn out to be misleading epiphanies. This is the high price to pay for arriving at a genuine possibility for hope and at an authentic experience of presence.

In The Arrière-Pays, as Bonnefoy revolves around “presence” and other aspects of his poetics, he tells the story of key experiences, thoughts, feelings, and intuitions, as well as trips made to Italy, books read, and paintings studied; which is to say that he recounts how he tries to make sense out of them and of himself. The book is, fundamentally, a spiritual autobiography; yet it draws extensively on the outside world and ponders how it can be described in writing or depicted in painting. Beginning with the mesmerizing sentence “I have often experienced a feeling of anxiety, at crossroads,” Bonnefoy (who, by the way, studied mathematics and art history) goes on to consider the blue in Nicolas Poussin’s Bacchanalia with Guitar Player, the island of Capraia, the hills in Piero della Francesca’s Triumph of Battista, travel writings by Ferdinand Ossendowski and Alexandra David-Neél, and much more.

The book, which also relates the tale of an unfinished novel (and why it remained unfinished), is as much a récit, a narrative, as a prolonged personal essay. As Romer puts it in his excellent introduction, there are “metaphysical false starts, red herrings, riddling enigmas and visionary moments” in The Arrière-pays, which “even has elements of the supernatural thriller.” This edition is graced with three recent texts, “September 2004,” “The Places of Grasses,” and “My Memories of Armenia,” which return to the themes of the original essay.

As has already been suggested, the title designates what is central here. In his preface, Bonnefoy writes of the decision to retain the French term in the English title:

The title of the book also proved to be a problem, since it takes on many nuances throughout the text. “Hinterland” has harsh, even military, associations to the French ear, and is quite unable to render what is a straightforward phrase, although it naturally sets the mind dreaming. In the same way, “back country” is too heavily charged with ideas of poverty or even backwardness, when my own arrière-pays is a dream of civilizations superior to our own. I found in the adjective landlocked” a good deal of what my phrase contains but then some examples of my arrière-pays are islands. . .

This image of “arrière-pays” derives from a conceit typically used in Italian renaissance painting, of which Bonnefoy is a scholar: beyond the portrait or the scene depicted in the foreground, a sort of dreamy, oft-mountainous, landscape can be seen in the distance. This remote landscape is like an “elsewhere,” an “over there”; in it we crystallize our hopes for “something more” than what we find in the here and now. As Bonnefoy notes in regard to the kind of “nostalgia” that is “a refusal of the world”:

Nothing . . . touches me more than the words and accents of the earth. I am at peace with my language, my distant god has only slightly withdrawn, his epiphany resides in the simple: and yet, supposing that the true life is over there, in that elsewhere I cannot situate, then what is here starts to look like a desert.

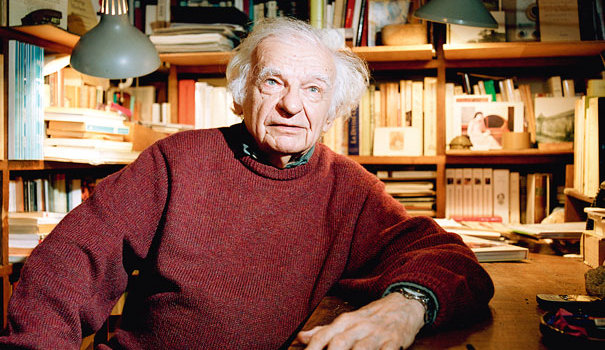

Poet/Essayist Yves Bonnefoy — he looks for “glimmers” of something perhaps transcending the here and now, the strictly material world of things.

In contrast to longing for what seems to have been lost or, especially, for what might be true or authentic yet remote, Bonnefoy thus underscores the importance of the here and now, of simple things; and his poetry, essentially all of which is available in English translation, makes ample use of stones, water, snow, trees, and other rudimentary elements of nature. (A perfect recent way to become acquainted with Bonnefoy’s work is Second Simplicity: New Poetry and Prose 1991–2011, translated by Hoyt Rogers, Yale University Press, 2011. See Arts Fuse review.)

Yet this purposeful dwelling on the here and now does not induce Bonnefoy to focus exclusively on things-in-themselves, on their strict material configuration, as if the object of poetry were a horizonless realism. The examination of simple things is always accompanied by a search for meaning, even if the “presence” intimated in their midst is perhaps ultimately one of emptiness rather than plenitude. A paradox is involved. Reading Bonnefoy can induce a feeling of plenitude, as it were; but this sentiment is probably more akin, ultimately, to a deep awareness of emptiness—as in oriental spirituality—than to the in-dwelling presences and fulfillments that we associate with Christian mysticism. In any event, the dialectics of fullness and emptiness crop up often in The Arrière-Pays. Bonnefoy makes these distinctions, for instance, while pondering his decision to abandon his novel:

The dream exists, too, but not to destroy or devastate [the being of the earth and the meaning of presence], as I had thought in my hours of doubt or pride: as long as I could dissipate the dream itself, without having written it, but lived it: for once it recognizes itself to be a dream, it is simplified, and the earth gradually returns. It is in my own becoming, that I can keep open—and not in a closed text—this vision, this intimate knowledge; it is there, it can take root and flourish and bear fruit if, as I think, it has meaning for me. That would be the crucible in which the arrière-pays, having dissolved, would re-form, and where the empty here and now would crystallize. And where a few words would shine, possibly, and while being simple and transparent—like that emptiness, language—would yet be everything, and real.

Other fine distinctions are made in The Arrière-Pays. After formulating his skepticism about “elsewheres,” for example, he makes the tour de force of arguing that it is not entirely satisfactory to reject all “elsewheres” out of hand. “I should make clear that if the arrière-pays has remained inaccessible to me—and even if it does not exist, as I know, as I’ve always known—,” he writes, “it is not, for all that, entirely unlocated, so long as I dispense with the laws of ordinary geographical consistency and the principle of the excluded middle.” (In Aristotelian logic, as Romer reminds us in a note, the principle of the excluded middle implies that “in propositional terms a is either b or not-b.” There is no third possibility.) Bonnefoy adds this telltale image: “In other words, the summit has a shadow, which hides it, but this shadow does not extend over the whole earth.” In his introduction, Romer makes several penetrating remarks about these paradoxes, all related to Bonnefoy’s notion of “presence” and, it seems to me, informed not only by his mathematical background but also by his early, if brief, association with French surrealism.

Moreover, The Arrière-Pays stimulates the reader into reconsidering his own quest. As Romer finely phrases it,

the other country, that remote region which can never be fully explicated, nor even definitively located, also allows for the supernatural descent, or for the approach of the absolute, as an integral part of our human experience. When Bonnefoy declares [. . .] “I love the earth, and what I see delights me,” he means just that. The moments of transcendence, of Presence, cause a joy that is essentially inward, but it is a joy, emphatically, mediated by the exterior. His vision is thus an open one that allows, and even encourages, each one of us to draw up a list of our own personalized “devotions.”

Put like that, the context of Bonnefoy’s poetico-philosophical pursuit no longer seems so complicated and intimidating. And it isn’t, after all. This is a book to be studied and savored. Moreover, among its invigorating qualities, it certainly acts as a corrective, or at least a challenge, to the sometimes naïve factual immediacy of so much contemporary Anglo-American poetry.

John Taylor has translated many French poets, most recently Jacques Dupin (Of Flies and Monkeys), Philippe Jaccottet (And, Nonetheless), and Pierre-Albert Jourdan (The Straw Sandals). He is the author of the three-volume essay collection Paths to Contemporary French Literature, as well as Into the Heart of European Poetry. He has written eight books of poetry and short prose, including The Apocalypse Tapestries, Now the Summer Came to Pass, and If Night is Falling.