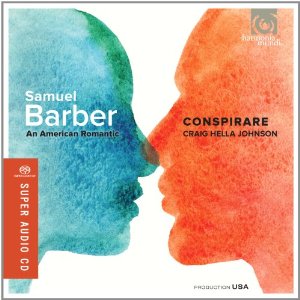

Classical CD Reviews: “Barber: An American Romantic” (Conspirare) and “Imogen Holst: Choral Works” (Choir of Clare College, Cambridge)

This recording makes as strong a case for Samuel Barber’s unjustly neglected choral music as any: it’s a disc not to miss.

Barber: An American Romantic by Conspirar. Imogen Holst: Choral Works. Choir of Clare College, Cambridge. Harmonia Mundi.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Despite its justly earned reputation as a period of often-unpredictable musical development, the twentieth century yielded a bountiful crop of magnificent choral music. From Britten and Stravinsky to Messiaen and Copland, massed human voices remained a significant means of musical expression, despite (or, perhaps, because of) the inhumanity occurring around many composers throughout the century. Owing to the amount that was written, much of the century’s choral music necessarily remains unfamiliar, though two albums recently released on the Harmonia Mundi label endeavor to rectify that situation, at least in part.

Samuel Barber is the focus of the Portland, OR-based ensemble Conspirare’s new disc, Barber: An American Romantic. Aside from his Agnus Dei (which profitably recycles the Adagio for Strings—which, in turn, had been arranged from the slow movement of his String Quartet), Barber’s choral writing gets relatively little airtime. And that’s a pity, as this sumptuously sung and recorded album demonstrates. Covering most of his compositional career, the selections feature texts by poets who were mostly Barber’s contemporaries, and showcase a greater stylistic breadth that Barber is often given credit for possessing. Yes, everything ends on a triad (or at least the suggestion of one), but in between is some of the most richly expressive music any recent composer has penned.

Of the 10 works included, the most substantial is The Lovers, Barber’s 1971 setting of selections from Pablo Neruda’s Twenty Poems of Love and a Song of Despair. Written during a period of great personal and professional conflict, this is music of anguished, yet direct, expression. Conspirare’s performance (which features the premiere recording of a new arrangement of the full orchestral score for chamber orchestra, expertly reduced by Robert Kyr) captures all its haunting sadness, bitterness, and beauty. Estell Gomez, Derek Chester, and David Farwig ably cover the solos.

Other highlights (and, in truth, it’s difficult not to just list all of the other nine works) include sensitive performances of Twelfth Night and To Be Sung on the Water (both written in 1968), a gripping account of A Stopwatch and an Ordinance Map (for male voices and timpani), and a moving reading of Sure on This Shining Night. Through the whole disc, Conspirare sings with excellent diction, tonal precision, and expressive refinement that is rare to come by. This recording makes as strong a case for Barber’s unjustly neglected choral music as any: it’s a disc not to miss.

A similarly unjustified bias has dogged the music (if not the musical reputation) of Imogen Holst, daughter of the famous Gustav and intimate of Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears, among others. She counted Herbert Howells and Ralph Vaughn Williams—two titans of the English choral tradition—among her teachers, though her own choral music, the subject of the Choir of Clare College, Cambridge’s new recording, possesses a distinctive voice of its own.

The selections on Imogen Holst: Choral Works span most of her career, from the early Mass in A minor (1927) to a 1972 setting of William Cleland’s “Hallo my fancy, wither wilt thou go?” To these ears, the most engaging work is a collection of three Psalm settings Holst composed in 1943. Written for chorus and strings, Three Psalms presents harmonic austerity and sensual beauty in striking combination. The strings of the Dmitri Ensemble accompany the Choir with understated eloquence.

Also notable are performances of “Welcome Joy and Welcome Sorrow” (which, with its harp and treble voice combination recalls Britten’s Ceremony of Carols on more than one occasion) and Holst’s orchestration of Britten’s 1943 festival cantata, Rejoice in the Lamb.

Throughout the Choir of Clare College, Cambridge sings with crisp diction, clear expression, and striking harmonic ease (which is especially impressive in Holst’s more deliciously chromatic moments). The Dmitri Ensemble provides sensitive accompaniment, and Graham Ross’s direction ensures readings that don’t dawdle but take time to enjoy the vistas here and there. It all adds up to a uniquely colorful, often serenely beautiful documentation of mid-twentieth century, English choral music by a significant composer who happened to be a woman, and one whose output ought to be better known than it is.

Tagged: Barber: An American Romantic, Choral Music, Harmonia Mundi