Poetry Review: Translucent Translations — “Wheel with a Single Spoke”

Nichita Stănescu is one of the poets who broke through the socialist-realism sound barrier and propelled Romanian poetry into new spheres.

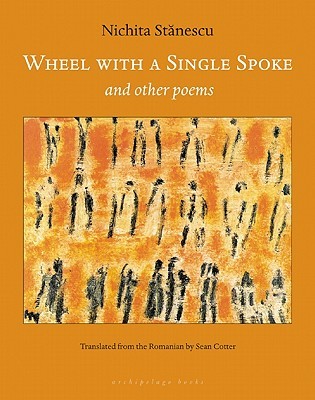

Wheel with a Single Spoke and Other Poems by Nichita Stănescu. Translated from the Romanian by Sean Cotter. Archipelago Books, 200 pages, $18.

By Ellen Elias-Bursac

Wheel with a Single Spoke offers a wide-ranging array of poems by Nichita Stănescu (1933–1983) in insightful translations by Sean Cotter. The poems cover over 20 years of publishing poetry, from the 1960s when Stănescu published his first verse up to his early death at the age of 50. For a poet who is thought of as one of the defining Romanian voices of the mid-twentieth century, Stănescu is poorly represented in English, with three slender collections published in the 1970s and 1980s. Archipelago’s fuller treatment is long overdue.

Like Cotter, I am a translator, but unlike Cotter I know no Romanian and until I picked up this book I knew nothing about Stănescu, so this review is like a tourist excursion into a hitherto unknown land. It was the drama of an early poem that first caught my eye:

…

And Autumn drove its prow

like an icebreaker

into the white quick of winter

and parted and crushed,

and shattered and broke it.

The woman shot a glistening

arrow into the air

a cry of joy

for her son.

…

(“The Right to Time,” 33)

Apples figure large in Stănescu’s figuration of reality:

I was never angry with apples

for being apples, with leaves for being leaves,

with shadow for being shadow, with birds for being birds.

But apples, leaves, shadows, birds

all of a sudden, were angry with me.

…

(“The Fifth Elegy,” 63)

As does the pull of gravity:

Because I walk on you,

you are covered in footprints.

My soles are worn through.

We only lose touch when I jump

or you cave in.

Where I end, you begin.

Glassy white, phantoms

reveal themselves: angels descend,

crystals rise.

Day descends upon night,

a continuous sunrise

over various planets.

…

(“Surface,” 73)

I was particularly drawn to the many poems about writing poetry, particularly this one, in which the poet portrays himself, arching in a translator-like span:

…

Then

I came to me,

I braced myself between two banks

of a river,

to present a bridge,

a bridge between a bull’s horn and grass,

between black stars of light and earth,

between the side of a woman’s head and a man’s,

letting words travel over me

like racing cars, electric trains,

only so they could cross faster,

only so they would learn to transport the world,

from itself,

to itself.

(“Ars Poetica,” 41)

And another:

A poet, like a soldier

has no life of his own.

His own life is wrecks

and ruins.

With the forceps of his cerebrum he lifts

the emotions of ants

brings them closer and closer to his eye

until they and his eye become one.

He puts his ear to the belly of a starving dog

His nose smells the half-open muzzle

until his nose and the dog’s muzzle

are the same.

During waves of heat

he fans himself with flocks of birds

he startles into flight.

None of you should believe a poet when he cries.

His tear is never his own.

He has wiped tears from things

and cries things’ tears.

…

(“A Poet, Like a Soldier,” 204)

Any reading of translated verse raises tantalizing questions about whether the words we are reading are the poet’s or come to us from the translator. In his Afterword to the volume, Cotter informs us that “Stănescu’s most paradoxical or surprising images are often delivered in regular or irregular rhymes. His rhymes are dazzling . . . so much so that they may detract from the sense of the line. Rather than adding meaning to the poem, the rhymes move us toward the aural edge of meaning, working like unwords . . .”

Of his task as a translator, Cotter argues that “the translated text seems transparent, in that it promises us another poetry, and yet it is merely translucent, in that we see that poetry’s light while noting our distance from the experience of its words. The task I set myself in translation is to maintain, as much as possible, that sense of the halo around the poems.”

Here are just a few examples of the ways in which Cotter maintains this sense of the halo, the many lines that resonate with assonance, rhyme, and music. We who speak no Romanian have to assume that these are somehow both Stănescu’s and Cotter’s.

In the lines below, Cotter builds the sound and rhyme structure with “kiss”, “yes” “bistro” and “as if”:

They kiss, yes, they kiss, they kiss,

the young, on a street, in a bistro, against a railing,

they kiss each other constantly as if they

were nothing but the endpoints

of a kiss

…

(“The Young,” 96)

In the poem “Fate” the consonance comes through the positioning of “you see” “leaf” “green” “screams,” “feel,” and “tree”:

When I opened my eyes, I was

set inside this body you see,

found guilty for the way I was,

guilty as a leaf for being green.

And suddenly I began to sense

the pace of screams and light

and feel the dolorous curve of dawn

and every tree, alive.

. . .

(“Fate,” 82)

The last poem of the collection is a brilliant example of this approach. Cotter tells us that it is also the last poem to be published during Stănescu’s lifetime. It is quoted here in full:

I thought of a way so sweet

for words to meet

that below, blooms bloomed

and above grass greened.

I thought of a way so sweet

for words to smash

that perhaps grass would bloom

and blooms would grass.

(“Knot” 33 “In the Quiet of Evening,” 264)

Stănescu is one of the poets who broke through the socialist-realism sound barrier and propelled Romanian poetry into new spheres. He has been revered for decades in Romania as a great voice and it is our considerable good fortune that Cotter has helped us to see why. For further reading see Andrew Seguin’s excellent review in Words Without Borders.

At Poets House, 10 River Terrace New York, NY, October 3, 7 p.m.

Join Archipelago Books, Poets House, and the Romanian Cultural Institute for a night of poetry in honor of Nichita Stănescu—”the greatest contemporary Romanian poet” (Tomaž Šalamun)—and Sean Cotter’s translation of Wheel with a Single Spoke and Other Poems. With readings by actor Vasile Flutur and Cotter, in conversation with Saviana Stănescu.

Tagged: Archipelago-Books, fiction-in-translation, Nichita Stănescu, poetry in translation, Romanian, Sean Cotter