Visual Arts: Bureaucratic Vandalism and the Survival of Sheer Excellence

In order to pay tribute to the supreme Frits Lugt and his Fondation Custodia—and to protest the announced closing of the Institut Néerlandais with which it is joined—the column describes an example of Lugt’s collecting genius.

By Gary Schwartz

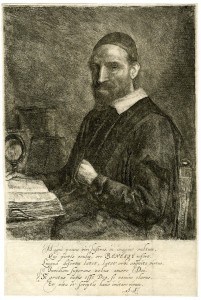

Only one artist born in my town of Maarssen, near Utrecht, has ever made it into the literature on seventeenth-century Dutch art, and even then only into fairly specialized books and catalogues. His name is Constantijn à Renesse or Constantijn van Renesse (1626–80) and he is a bit of an art-historical outsider. His father Lodewijk (1599–1671) was a prominent theologian who from 1620 to 1634 was the preacher of the Reformed Church of Maarssen. Lodewijk’s father Gerard, an officer in the States Army, had been killed at the siege of Ostende in 1603, and in 1631 Lodewijk himself entered military service as a part-time chaplain. In 1637 he participated in the recapture of Breda from the Spanish. At that juncture, he was asked by the commander-in-chief, Stadholder Frederik Hendrik, to take on the formidable (in fact impossible) task of protestantizing Brabant. Judging from his portrait by his son, he looked like the man for the job.

Constantijn van Renesse (1626-80), Portrait of the artist’s father, Lodewijk van Renesse (1599-1671), signed CARenesse and C.R. fe., with Latin verse by Arnoldus Senguerdus (1610-67), ca. 1660s. Etching, 24.9 x 20.4 cm. Hollstein 13ii. London, British Museum

Constantijn van Renesse, Portrait of the artist’s son, Lodewijk van Renesse (1655-1739), Signed and dated CARenesse f/1669. Black chalk and red chalk drawing on vellum, 9.6 x 13.7 cm. Last reported at the C.R. Rudolf sale, Amsterdam (Mak van Waay), 18 April 1977, lot 122. Geneva, collection of Jean Bonna

Touchingly, Constantijn also left us a portrait drawing, dated 1669, of his sweet-looking, oldest son (1655–1739), named Lodewijk after his grandfather. To judge by his epaulettes and the bands hanging from his collar, items worn by attorneys, preachers, and academics, the drawing must have been made around the time when the 14-year-old boy matriculated at university. If so, he could have belonged to the last class to enter the ill-fated institution of higher learning founded by his grandfather in 1646. The “illustrious school” of Breda, which always had a marginal and controversial existence, was disbanded in the very year of 1669.

The unsung hero of Rembrandt school studies, Werner Sumowski, attaches some 85 drawings to the name of Constantijn van Renesse, in various shades of attributional certainty and physical survival. They show the artist to have been a thinking man, with broader interests and greater self-reflection than most of his colleagues. As dedicated as he was to drawing, painting, and printmaking, he was too well-born to be a professional artist and to submit to the authority of a craftsman’s guild. In 1653 he became town secretary of Eindhoven, a post he held for the rest of his life.

In any case, I was delighted when Peter Schatborn, in his catalogue of drawings by Rembrandt and his school in the Frits Lugt Collection (2010), attributed to van Renesse a tender portrait drawing of a young man. Standing in roughly the same pose as Lodewijk, though in reverse, is a somewhat older boy, dressed not in the fancy garb of his son but in the working-class clothes of an assistant or apprentice to a craftsman.

Constantijn van Renesse, Standing boy with a cap, drawing in pen and brown ink, 16.6 x 10.9 cm. Paris, Fondation Custodia, Frits Lugt Collection, inv. nr. 5992

The drawing was acquired in 1948 by Frits Lugt (1884–1970) as “attributed to Rembrandt,” but Lugt was convinced that it was by the master himself. In his new catalogue of drawings by Rembrandt and his school in the Frits Lugt Collection (2010), Peter Schatborn attributes the drawing for the first time to van Renesse. The resemblance to the drawing of Lodewijk, which Schatborn does not mention, convinced me immediately that he was right.

A third artist to whom the drawing has been attributed is Rembrandt’s friend and associate Jan Lievens (1607–74). A talented engraver made a copy of the drawing, printed in reverse direction, to which he added the letters I. L., Lievens’s monograph. There might be impressions of the print elsewhere, but the only one I have been able to find is in the Frits Lugt Collection, keeping company with the drawing.

Attributed by Peter Schatborn to Jan Pieter de Frey (1770–1834), engraving after drawing of apprentice, with monogram IL. Paris, Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, inv. nr. 6024

The reproduction is assumed by Peter Schatborn, reasonably, to have been made by Jan Pieter de Frey (1770–1834), a Dutch printmaker who specialized in work of this kind. A comparison of the reproduction print to van Renesse’s drawing of his son Lodewijk, with their shared hanging-arm pose and interest in the niceties of professional costume, delivers the kind of evidence for an attribution that to my mind is as firm as it comes.

Schatborn recognizes in the boy’s features the same youngster who figures in a famous drawing from the Rembrandt school showing a life class given by a master, a drawing that is currently also ascribed to van Renesse. If so, then we are looking twice at a young Rembrandt pupil of about 1650. The dating is based on what we know about van Renesse’s doings. He would not have been around after his appointment in Eindhoven in 1653.

Possibly Constantijn van Renesse, A master giving drawing instruction to an older pupil. Black chalk, brush and brown wash, heightened with white, 18 x 26.6 cm. Early 1650s. Darmstadt, Hessisches Landesmuseum, inv. nr AE665

The identity and behavior of the various male figures—the role of the female is clear—are fascinating to contemplate. The bearded man with glasses looks like one of the amateurs who were said to take lessons from Rembrandt. The bareheaded youngster peeping over their shoulders would seem to be a senior apprentice. The two somewhat older men on the left both have books, one open and the other tucked into his sleeve. Let us call them kibitzer connoisseurs. The sitting boy looks like a junior apprentice, enjoying tuition while performing chores in the studio. Whether he is really the same model as in the portrait drawing I would not say as confidently as Schatborn, but he is surely of the same type. Nor is it certain that the master artist is intended to represent Rembrandt. Lugt thought he wasn’t. Whether Rembrandt or not, the cast of characters in the drawing corresponds to reports of the denizens of the Rembrandt studio.

Frits Lugt could not get his hands on the drawing in Darmstadt, but in 1919 he was able to acquire the next best thing, an old copy after it.

Copy after Rembrandt school drawing in Darmstadt. “Point of the brush in brown and grey ink, brown and grey wash, traces of a sketch in pencil” (from Peter Schatborn’s catalogue), 19 x 27.2 cm. Paris, Frits Lugt Collection, Fondation Custodia, inv. nr. 337

This column began as a tribute to Frits Lugt and Fondation Custodia, for which the drawing of a boy by Constantijn van Renesse was only supposed to be an illustration. But I was unable to show and explain the material more briefly than in 1,000 words. Therefore, rather than expatiating on the sheer excellence of Lugt, his successors and the staff of Fondation Custodia, let this constellation of two drawings and a print, with attendant materials, stand as a demonstration of Custodia’s almost painfully exquisite supremacy. Those three items did not come in, as the holdings of most collections of that size, in inherited chunks. They were culled for their art-historical interest and understated quality by highly sophisticated collectors. That Lugt’s efforts, though those of a private individual, were cumulative and have built up into a depository and research center of unique value, is a surpassing treasure. Adding to the significance of the holdings and their maintenance by top specialists is that Custodia is located in Paris, where it has far greater impact than it would in the Netherlands.

In 1957 Frits Lugt succeeded in linking Fondation Custodia to a Dutch government institute for Netherlandish culture on the Rue de Lille, the Institut Néerlandais, headed by the cultural attaché of the Netherlands embassy. The Institut Néerlandais and the Fondation Custodia form a mutually dependent beachhead for the Netherlands in a city that is still one of the great world centers for art and history. Compared with the dozens of other national foundations of this kind in Paris, the Dutch entry is one of the most prominent; in terms of the value of its artistic holdings, it stands in lone isolation at the top. The presence of Custodia in the Institut Néerlandais is an inimitable compliment both to the Netherlands and France and a model for international cooperation at the highest level.

My reason for putting this down in words at this time is not pretty. In July the Dutch government announced that it is discontinuing its €1.8 million budget for the Institut Néerlandais, that it is taking the cultural attaché back to the embassy and will thenceforth run Dutch cultural activities in Paris from behind barricaded doors there, with no further staff support.

The careless ignorance underlying this act of bureaucratic vandalism is exemplified by the stupid errors in the press release by which the government announced the move: “The Ministry wishes to thank Fondation Custodia—its partner and co-founder of the Institut Néerlandais—for their many years of productive collaboration, and for Custodia’s role in promoting Dutch art in France. The fine reputation enjoyed by Dutch heritage there is largely due to the active management of the art collection from the legacy of the late nineteenth-century collector Fritz Lugt.” The Netherlands Ministry of Education, Culture and Science does not know that Lugt was a giant of the twentieth century, down to the threshold of our time, or the spelling of his first name. The unwillingness of the government to uphold its share in that “productive collaboration” is robbing Custodia of a well-established showcase for its exhibitions and dislocating it in other ways as well. Perhaps worst of all is that the Dutch government, after having benefited for half a century from the prestige emanating from Lugt’s priceless initiative, is dragging the country down in shame out of the pettiest of narrow-minded considerations.

I can only hope that the outrage engendered by this incomprehensible misstep will shake some sense into the heads of the responsible politicians and bureaucrats before it’s too late.

Peter Schatborn, Rembrandt and his circle: drawings in the Frits Lugt Collection, 2 vols., Bussum (Thoth) and Paris (Fondation Custodia) 2010. Set in the Custodia, a magnificent, idiosyncratic typeface designed for the Fondation by Fred Smeijers

In 2010 a biography of Lugt written for Custodia by Freek Heijbroek was published in Dutch. An English translation appeared in 2012, under the title Frits Lugt 1884-1970: living for art, Bussum (Thoth) and Paris (Fondation Custodia) 2012

Werner Sumowski, Drawings of the Rembrandt school, edited and translated by Walter L. Strauss, vol. 9, New York (Abaris Books) 1985, pp. 4813-4955

For a portrait by Constantijn van Renesse that has been identified tentatively as a painted portrait of his father, see David de Witt, The Bader Collection: Dutch and Flemish paintings, Kingston, Canada (Agnes Etherington Art Centre) 2008, pp. 274-75, cat. nr. 166

© Gary Schwartz 2012.

Gary Schwartz was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1940. In 1965 he came to the Netherlands with a graduate fellowship in art history and stayed. He has been active as a translator, editor, and publisher; teacher, lecturer, and writer; and as the founder of CODART, an international network organization for curators of Dutch and Flemish art. As an art historian, he is best known for his books on Rembrandt: Rembrandt: all the etchings in true size (1977), Rembrandt, his life, his paintings: a new biography (1984) and The Rembrandt Book (2006).

His Internet column, now called the Schwartzlist, appeared every other week from September 1996 to April 2007 and has been appearing since then irregularly.

In November 2009, Schwartz was awarded the coveted tri-annual Prize for the Humanities by the Prince Bernhard Cultural Foundation of Amsterdam.

Responses always welcome at Gary.Schwartz@xs4all.nl.

Tagged: Constantijn à Renesse, Fondation Custodia, Frits Lugt, Maarssen, Peter Schatborn, Rembrandt