Critical Commentary: John Updike and the Pleasures of the Imported Gadget

One of the late John Updike’s most impressive critical strengths is that he was one of the few high profile reviewers who regularly commented, with perception and equanimity, on fiction in translation.

by Bill Marx

John Updike — for him, the communion between reviewer and his public is based upon the presumption of certain possible joys of reading, and all of our discriminations should curve toward that end.

Along with compliments to the late John Updike’s fiction, poetry, and writings on golf, a few hosannas to his literary criticism popped up, though the admiration lacked the merit of specificity. While Updike’s fiction attracted well-worn praises like flies, particularly talk about silken sentences lovingly dedicated to the surfaces of everyday life, remarks about his nearly five decades of reviews boiled down to astonishment at how many good ones he cranked out over the years. No one put his or her finger on what made Updike an interesting book critic, aside from cliches about his dedication to the task and mastery of the craft.

One of his most impressive critical strengths is that he was one of the few high profile reviewers who regularly commented, with perception and equanimity, on fiction in translation. Over five decades of writing on books he critiqued dozens of authors from the four corners of the globe, from Umberto Eco, Bruno Schulz and Italo Calvino to Czeslaw Milosz, Michael Tournier and Harry Mulisch. Unlike Edmund Wilson, another American critic who covered the international literature beat; Updike didn’t cultivate a mandarin image or work at picking up foreign languages.

Neither was his cosmopolitan literary interest of the Susan Sontag variety. He didn’t see himself as a cerebral cheerleader, a hunter/critic spotting grand ideas and essential visions in neglected books from across the seas. There’s a need for critics who, though prey to hyperventilation, see that contemporary international literature has something essential to offer American readers, whipping readers of their reviews into passionate intellectual frenzies about the necessity of exploring new voices outside of our own borders.

Eventually, Updike tried to keep up with the professional enthusiasts and supplied portentous blurbs for the literati. He didn’t care all that much for Polish writer Witold Gombrowicz’s novel “Ferdydurke” when he reviewed it in the 1970s: “Myself, I must register my sensation that Ferdydurke, a book about the imposition of form, has itself more the form – the assurance, the daring – of greatness than the substance. Beneath the energetic surface there is a static difficulty of event.” A couple of decades later he hailed Gombrowicz as “one of the profoundest late moderns.” The earlier piece is much more compelling, even if you don’t agree with it, because Updike reacts as a craftsman to something he doesn’t think works: he wasn’t in the professorial business then of giving late moderns grades for profundity.

At his best, Updike didn’t make foreign language literature sound cool or indispensable. He was the skeptical technician patiently taking another writer’s measure. The tools he used to create finest fiction – dedication to the prosaic and domestic, skepticism about the fantastic and the supernatural, commitment to dulcet phrasing, preternatural powers of observation — limits the scope of his insights, but not their earnest penetration, subtle discriminations or his refreshingly buoyant curiosity.

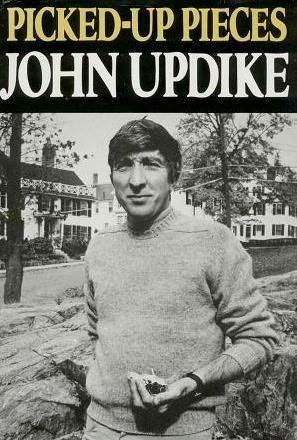

Updike talks about the reasons behind his dedication to literature in translation in his second collection of non-fiction, 1975’s Picked-up Pieces. His choice turns out to be rooted in a lit-crit political/ethical quandary rather than an instinctual preference. He didn’t feel comfortable reviewing his contemporaries (who could always return a pan), and understandably fearful that he will be charged with conflict of interest. So Updike decided it was safer to check out what was happening elsewhere:

“As an aspiring American writer myself, I clearly could not be trusted to clip the tender new shoots of my competitors. The esoteric fiction of Europe, however, was an ocean removed from envy’s blight, and my practitioner’s technical side was glad to investigate imported gadgetry. Borges, Queneau, Pinget, van Ostaijen, Cortázar – I am happy thus to have made their acquaintance, and made note of their lessons. Sure enough, when an American (Kosinski, Piercy) or an Englishman (Aryton, Collier) got mixed into my periodic dose of the avant garde, a brusquer assurance and a chummy impatience did creep into my tone, which when dealing with translated works assumed the even omnivorous rumble of the grist mill.”

His use of the word “esoteric” and “imported gadgetry” suggest Updike’s approach in this collection of international fiction-as-gadgets-for-the-grist-mill. But he is a fine appreciator of the fine art of mechanics, as he shows in his appreciation of Raymond Queneau’s The Flight of Icarus in Picked-up Pieces:

The same spirit, perhaps traceable to a particular delight in Reason and its works, permits the French, uniquely, to produce works of art as intellectual, spare, and impudent as this, as spindly and nakedly theoretical as a primitive machine yet undeniably serious, even majestic.

When he reviews fiction in translation Updike comes off as a sophisticated American mechanic inspecting a fancy foreign automobile: poking with under the hood, admiring the pizazz of the chassis and the intricacy of the engine, but puzzled by the square dashboard and the wobbly spin of the wheels. And the car better have zip, the smooth speed of a realistic American sedan –- one of his favorite words to denote dismay is “static.” An Updike review of foreign literature feels a bit distanced, wary of whether he can, or even wants to, understand a hunk of exotic machinery, the extra-suburban. He calibrates his judgments accordingly, and that leads him into some misjudgments.

But we read critics to explore how to think about art, not what to think about it. Let’s hope someday Knopf will pull Updike’s book reviews out of his intimidating line-up massive non-fiction gatherings. It would be nice to have a quick way to refer to Updike’s distinctive American pragmatism in the face of a foreign enticements.