Book Review: “Jane Eyre” Rewired — “The Flight of Gemma Hardy”

Author Margo Livesey has pulled off a considerable literary trick: a page-turner that is also a moving, realistic, subtle, and eminently wise coming-of-age novel.

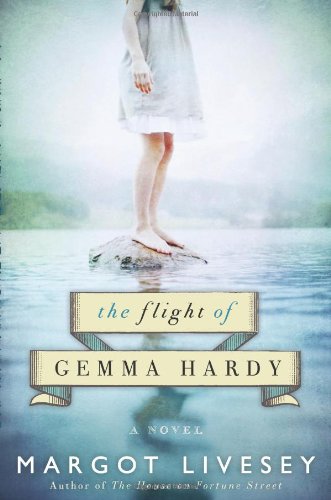

The Flight of Gemma Hardy by Margot Livesey. Harper, 464 pages, $26.99.

By Eric Grunwald.

A modern retelling of Jane Eyre might not seem the thing the world is crying out for, nor the most compelling reading. Both assumptions would be wrong. Margot Livesey’s new novel, The Flight of Gemma Hardy, a retelling and recasting of that Victorian “classic,” is a mysteriously marvelous tale that always feels both real and, like John Gardner’s “vivid dream,” seems at once both of the nineteenth century and of today. Livesey has pulled off a considerable literary trick: a page-turner that is also a moving, realistic, subtle, and eminently wise coming-of-age novel.

Most of the plot mirrors that of its literary predecessor. Gemma is an orphan who has lived for several years in uneasy comfort with her uncle and his family. When the novel opens in 1958, however, her uncle, a pastor whose kindness toward Gemma was both her salvation and her protection, has died, and Gemma’s aunt and cousins quickly reveal their true colors. “None of them seemed to notice that my uncle was missing,” Gemma tells us; she herself becoming persona non grata, “no good for even praise” let alone for accompanying “the Hardy family” anymore to the local Christmas party.

Relegated to virtual scullery maid, Gemma’s only solace is her uncle’s study, where she sits at the window with his Birds of the World and, belying early the symbolic pun in the book’s title, “flew away into the pictures.” On one such occasion, she startles her cousin Will, who beats and kicks her. Gemma’s aunt, listening to her son’s lies, coos, “You poor boy. I don’t know what your father was thinking when he brought such a minx into our home,” then tells the maid, “Lock [Gemma] in the sewing room.” There in the close, dark space, Gemma sees what seems to be a ghost—though not, as in Jane Eyre, specifically of her uncle—and falls into a fit.

The kindly doctor who attends her discovers how unhappy she is and arranges for her to go away to a boarding school. It is here we begin to see the biggest difference between Livesey’s novel and Bronte’s. Upon her analogous departure, Jane gives her aunt a speech, telling her, “I am glad you are no relation of mine. I will never call you aunt again as long as I live. . . . I will say the very thought of you makes me sick, and that you treated me with miserable cruelty. . . . You think I have no feelings, and that I can do without one bit of love or kindness; but I cannot live so.”

The speech is the beginning of Jane’s liberation: “Ere I had finished this reply, my soul began to expand, to exult, with the strangest sense of freedom, of triumph, I ever felt.” As with the ghost, though, Livesey’s approach is blessedly subtler, and Gemma’s departure happens abruptly with barely a word. Not only is this more realistic—as even Dickens, who is frequently invoked here, well knew (Oliver Twist was hardly capable of such speeches)—it also allows Gemma’s feelings to reveal themselves gradually as Livesey sprinkles clues and understated revelations throughout the book. Much later the aunt, for example, facing Gemma once again, tells her, “But you can’t possibly think worse of me than you already do.” Gemma tells us simply, “It did not occur to me to contradict her.”

Livesey’s restraint derives not only from intelligence nor just from the customs of contemporary fiction. She also has other, deeper fish to fry. Probably the word most often used by other characters to describe Gemma is “determined.” However, just as Jane could not thrive without love or kindness, Gemma’s subsequent wanderings are also largely a search for these. As the Donne-based sermon her uncle was working on the morning he died reads, “We each begin as an island, but we soon build bridges . . . connecting him or her to others, allowing for the possibility of communication and affection.”

But there is no question that determination is crucial to Gemma’s surviving the miserable boarding school (Claypoole, invoking one of Oliver’s tormentors) and managing to get educated amidst more cruelty; to her thriving as a private nanny and tutor; and to her resisting the dashing Mr. Sinclair and his dark secrets and the bookish, young man who rescues her later from her homelessness and sickness.

It is here, though, that Flight sheers away from the mother plot. Gemma, poised to enter the university and finding she still has feelings for one of these men, realizes that “I don’t think I can go forward until I know what lies behind me” and seeks to return to Iceland, the country of her birth, to find her true name and any remnants of her family.

Born and raised herself in Scotland, Livesey has lived and written in the U.S. for years (she currently teaches creative writing at Emerson College), and one thus might reasonably ask whether The Flight of Gemma Hardy, despite its European setting, is an American coming-of-age novel or a British one. In terms of the independence and self-determination Gemma ultimately demands, one cannot help but think Livesey has been influenced by her stateside sojourn. In terms of structure, however, the question is largely moot.

In his influential critical study The American Adam, published in 1955 five years after The Catcher in the Rye, R. W. B. Lewis maintained that the protagonists of American novels of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries had been Adam-like, partaking of “the American myth [that] saw life and history as just beginning.” This myth, as Kenneth Millard notes, saw the United States “originat[ing] as a nation by means of a decisive break with an Old World that had grown corrupt and moribund.” The American literary hero was thus “the authentic American as a figure of heroic innocence and vast potentialities, poised at the start of a new history.” Hence Holden Caulfield’s initial dismissal of “all that David Copperfield crap.”

It’s Holden’s but not Salinger’s, for as Pamela Steinle points out in her fascinating In Cold Fear, exploring the censorship battles around Catcher, Holden’s opening may have been his own defense of “his position as solitary individual in the Adamic tradition,” but it was also an “implicit jab” by Salinger at modern readers moving away from English literary tradition. Indeed, Holden’s own flight—from school, family, and past—don’t save him, and in the shell-shocked wake of World War II and the bomb, Lewis spoke for many when he wrote, “We can hardly expect to be persuaded any longer by the historic dream of the new Adam.”

The trend of American coming-of-age novels, says Millard, has thus been toward “walking the line between presenting its protagonist as a newborn who is innocent of history and of depicting a protagonist whose coming of age consists principally of acquiring historical knowledge.” Thus Russell Banks’s wonderful Rule of the Bone (1994), in which 14-year-old Chappie/Bone can only mature by not only finding his real father, who left when Chappie was five but also accepting uncomfortable truths about the U.S.’s slave-built past. Moreover, by accepting the inadequacy of his real and surrogate fathers, Chappie is able to expunge the sense of “sinfulness,” as Millard puts it, that he’d acquired not only from his culture but his “initial predicament as [a] fatherless child.”

All of which Gemma also goes through in The Flight of Gemma Hardy. She comes to know her own true name and family and, even as she realizes her own ability to lie and steal, sheds the sense of guilty inferiority inherited from her early situation. And there is a subtle but implicit critique of Scottish culture here.

So is it an American novel, then? The original Jane Eyre, after all, has no such homecoming or discovery of truer roots. Perhaps, but Dickens’ characters did, particularly Oliver Twist, and the many references in Flight, including one description of Gemma’s dress as “positively Dickensian,” confirm Livesey’s debt to that author who had known such a troubled early history himself. While Livesey may be part of a trend of American writers whose protagonists move forward only by looking back, the entire movement looks back with nary a grain of nostalgia: the goal is to grapple with a supposedly “corrupt and moribund” earlier history. And in a post-9/11 world where our president is a living reminder of a past many would rather forget—or perhaps repeat—such a trend is a welcome thing.

Sounds like a great read – can’t wait to check it out!