Theater Commentary: Isn’t It a Question of Relevance?

More than any other art, theater asks for relevance. A play that convinces us that “this is the way it is now” can be excused many shortcomings. At any one moment there is a particular quality of feeling which dominates in human intercourse, a tonality which marks the present from the past, and when this tone is struck on the stage, the theater seems necessary again, like self-knowledge. – Arthur Miller, “What Makes Plays Endure?”

All My Sons may no longer fit Arthur Miller’s demand for relevance in the theater

By Bill Marx

Arthur Miller’s notion of relevance in the theater, in light of the recent New York Times (NYT) article on the reluctance of our non-profit theaters to stage new plays by non-brand name playwrights, has been on my mind lately. I have also fielded, offline, a couple of comments from people puzzled by the characterization of Miller’s All My Sons as an “arthritic war horse” in my February theater recommendations.

The questioners want to know what I am talking about. The reviews of the Huntington Theatre Company (HTC) production were generally ecstatic. And what could be timelier than an oft-produced American drama that focuses on the tragic costs of war profiteering?

For Miller, relevance in the theater means that companies have to do the hard work of staging plays by playwrights that convince us that “this is the way it is now.” (An aim that is not limited to realism.) To my mind, Miller’s 1947 play no longer lives up to his own high but fair standard. In an age of Halliburton and Blackwater, it is part of the past, a reassuring morality tale as well as an easy exercise in nostalgia.

The American Repertory Theater’s next production raises issues about theatrical relevance as well: Clifford Odets’s Depression-era epic Paradise Lost is rarely produced and I am very curious to see it, but why must companies go back decades, via Miller and Odets, to deal with present-day American realities? Are there no playwrights writing scripts of merit about life today? I find it hard to accept, given that hundreds of playwrights graduate from American colleges and universities every year, some from the very institutions that are pumping out “bold” productions of Odets and Miller.

New plays don’t have to be perfect. As Miller says, audiences will overlook problems in dramas that earn our attention by making the theater seem necessary again. But fresh scripts are difficult to market, even in an age of Facebook and tweeting. The issue raised by the NYT article is that non-profit theater’s dependence on brand name playwrights and state-of-the-art publicity sidesteps the essential challenge of making the stage seem necessary in a culture where it is increasingly marginalized.

Along with All My Sons I will talk about a few other Boston-area productions over the past few months that courted relevance: Ian Bruce’s South African drama Groundswell at the Lyric Stage, Bread & Puppet Theater’s Tear Open the Door of Heaven, and David Rabe’s exploration of euthanasia in A Question of Mercy, staged by the Boston Center for American Performance at Boston University. All of the shows are closed.

Will Lyman (Joe) and Karen MacDonald (Kate) in the HTC production of All My Sons

In 1947 All My Sons jolted audiences, much to Miller’s surprise because he wrote the play during World War II and felt the script’s message of American moral myopia had already become dated. Manufacturer Joe Keller is exonerated after being charged with shipping damaged airplane cylinder heads out of his factory, inadvertently causing the deaths of 21 pilots. For three and a half years, he has placed the blame on his partner and former neighbor. The truth, which his neighbors and wife Kate know full well, is that Joe is guilty, that he lied his way out of jail.

The far-too-neatly wound Ibsenesque plot (Miller copies the master’s compactness, but shares none of Ibsen’s impatience with the rules) focuses on the issue of the Kellers (Kate, Joe, and son Chris) facing responsibility for their complicity in the murders. The issues are tailored for maximum didactic impact.

This heavy-handed fable of crime and punishment was fine over 50 years ago, but a revamped version of All My Sons should be considerably more complex and troubling, thus more relevant and necessary. Halliburton’s documented cases of war profiteering during the Iraq War were sanctioned (indirectly) by the government as well as protected by the company’s ties with the powerful. Joe Keller is fairly successful, but he’s far from a contemporary mega-millionaire defense contractor who can buy lobbyists and media image-makers by the handful. Today, Joe’s partner would be fully protected—it would be the whistle blower who would be destroyed or pushed aside.

Now Joe’s neighbors would most likely be shareholders in Keller’s company—thus directly implicated in his “blood” money. They would have a financial interest in seeing that Keller was not caught, that the facts about the company’s malfeasance not come out, so that the profits would keep growing. Miller says the play is about how “the chickens come home to roost.” But a present-day All My Sons would have to tackle our increasingly sophisticated, technologically-enhanced allegiance to obfuscating the truth—it is in the interests of the many for the sake of the “brand” that the birds stay far from the coop.

Other once critical aspects of the play are fangless today. Miller’s critical images of Americans hammered by business, of men yearning for freedom from their henpecking wives, carries an antique punch. Aside from the abstract backdrop of the set, the HTC production missed opportunities to freshen up the play, especially concerning the character of Joe. Will Lyman’s Joe was amiable and befuddled—he believed that he covered up his crime for the sake of his family. The actor’s wan characterization emphasized the pathetic, playing up a vulnerability that Miller acknowledged in his plays—his inability to dramatize evil.

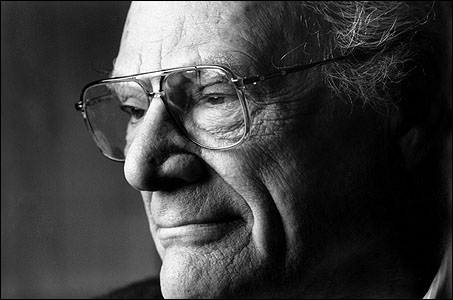

James Whitmore: His Joe Keller was a dangerous man

The late James Whitmore came up with the best version of Joe I have seen; the actor combined a steely egotism with a likable folksy quality. Taking his cue from suggestions in the script, Whitmore put up an expert front, which is what it takes to get ahead in America. The actor showed that, beneath the heartland friendliness, Joe seethed with selfish anger, a byproduct of the ruthless drive and corner cutting it took for an immigrant to build a company and become a pillar of the community.

Whitmore’s Joe was a dangerous man. Aristotle says that man’s only way to achieve immortality is through our children. Whitmore’s Joe did what he did not so much out of love or family values, but because this was how he would control his power and name into the future. With a weak Joe and a shouty Chris, the HTC production of All My Sons ambled along on the sturdy back of Karen MacDonald, who gave a rich and nimble performance as Kate, interjecting humor and pathos into the script’s maternal whip hand of denial.

Another attempt to “mark the present from the past,” Groundswell at the Lyric Stage, dealt with standard issues of white guilt in the post-apartheid era. Slackly directed by Daniel Gidron, the predictable, message-heavy drama-thriller by Ian Bruce revolves around two friends, one white and one black, at a beachfront guesthouse in an out-of-the-way South African city. The desperate pair needs money to invest in a diamond-mining venture (a possible scam?) and they see an opportunity for backing from an elderly, white visitor they believe to be wealthy.

Events quickly escalate into threats of violence (this is a play that depends on cut phone lines) that lead to revelations of racial crimes, with the white characters nearly confessing their sins of omission and commission to the audience. Mention of a dark secret and a glimpse of a knife early on suggest just where the play is going to go.

As explorations of white guilt go, this one generates some power by the end, but since the mid-90s a black government has controlled South Africa. It would be fascinating to see a play that focuses on the pressures, political and personal, that leadership and responsibility imposes on blacks during a period of rampant crime and controversies over AIDs, white flight, etc.

Lyric Stage performers Richard McElvain (Smith) and Timothy John Smith (Johan) face off in Groundswell

The Lyric Stage production floundered on Richard McElvain’s mannered performance as the wealthy geezer, Smith. I give a performer two or three physical tics in a role, but McElvain sported half a dozen, kicking the whiny figure into clown territory. As Johan, an alcoholic, former policeman, Timothy John Smith supplied neither the wily charm nor the hostile gusto that the role demands. Jason Bowen provided a skillfully restrained performance as a black man who tells the truth, even with a knife held in front of his face.

Bread and Puppet Theater (BPT) goes after the “brand new papermache religion” in its latest extravaganza, Tear Open the Door to Heaven. The anti-human creed under fire appears to be Judeo-Christian and its delusive and hypocritical promises of deliverance for the weak and downtrodden. At least that’s what I think the group’s lampoon is aimed at—the show mixes playfully surreal antics leveled at capitalist greed with interludes of downright inscrutable rhetoric. Compounding the difficulty: BPT’s artistic maestro Peter Schumann speaks with such a thick German accent that was impossible to make out what he was saying.

The Moslem religion didn’t appear to be one of the targets, even though some of its adherents commit repression and murder in the name of righteousness, suggesting the convenient, knee-jerk partiality of Bread and Puppet’s attack. The West and its allies are the all-purpose boogeymen—apparently not all the doors of heaven need to be kicked in.

Bread and Puppet Theater: Some of those volunteering to tear down the doors of heaven

Still, it was one of the group’s livelier shows of late, offering up vaudeville salutes to socialism and antic raspberries to the free market that would dunk the heart of a tea-bagger in acid. The puppets and drawings were as eye-catching as ever, the Second Line Social Aid and Pleasure Society Brass Band was killer, and there were amusing satiric jabs at high culture (corporate shilling sung to opera), NPR (a ditsy reporter is pushed out of a “cheap art” studio), and some funny dance numbers from the Lubberland National Dance Co., a ragtag group of performers in suits who jitter and slide across the stage. My favorite hoofing was the “Deforestation Dance to Create Parking for the Deforesters.”

The relevance of the show? Foggy, perhaps counterculture retro. But BPT remains, after decades, a radical war horse that hasn’t developed a full-blown case of arthritis yet.

The production that came closest to meeting Miller’s demand for relevance was A Question of Mercy, which tackles the thorny issue of euthanasia. Based on the real life experiences of surgeon and writer Richard Selzer, David Rabe’s 1998 play isn’t perfect by a long shot. The central character, based on Selzer, is left irritatingly underdeveloped (Paula Langton’s shaky performance as Dr. Chapman didn’t help), and the physician’s decision to help a man grievously ill with AIDs commit suicide is left unchallenged. Worse, Rabe unsuccessfully attempts to tap into the figure’s inner life and crippling doubts via a set of uninspired dreams.

But the tale of Anthony and his quest to end his unbearable suffering and die with dignity resonates, setting the power of the state and religion against the free will of the individual, who not only has to deal with his own fears and physical decay, but with the understandable reluctance of his lover and friends to help him. What’s more, the process of dying is not what it used to be. In his program notes, Boston Center for American Performance (BCAP)director Jim Petosa writes that as “the science of technology makes strides . . . our culture has moved little in terms of dealing with so-called ‘end of life issues.’”

This is just the ambiguous territory, the “bloody crossroads” of technology, politics, and freedom where the theater should be if it is to be relevant rather than au courant. When I saw the BCAP production on a weekday in mid-December there were only six people in the audience. One of them was Boston University’s George Annas, an expert in health law, bioethics and human rights, who was there to take part in a post-show talkback. Miller believed that the theater is asked to deal with “the way it is now.” He doesn’t say that audiences will want to face it, but that doesn’t lessen theater’s obligation, though many would like it to. Maybe it was a matter of Rabe’s dramatic approach—perhaps, a la Gatz, a performer should have read Seltzer’s essay, with the performers ingeniously worked into the presentation.

This is just the ambiguous territory, the “bloody crossroads” of technology, politics, and freedom where the theater should be if it is to be relevant rather than au courant. When I saw the BCAP production on a weekday in mid-December there were only six people in the audience. One of them was Boston University’s George Annas, an expert in health law, bioethics and human rights, who was there to take part in a post-show talkback. Miller believed that the theater is asked to deal with “the way it is now.” He doesn’t say that audiences will want to face it, but that doesn’t lessen theater’s obligation, though many would like it to. Maybe it was a matter of Rabe’s dramatic approach—perhaps, a la Gatz, a performer should have read Seltzer’s essay, with the performers ingeniously worked into the presentation.

Of course, that would have meant forgoing the production’s most haunting scene. Tim Spears, as Anthony, is on stage alone, trying to commit suicide by taking pills in a strictly prescribed fashion. He thinks that if he fails the doctor will come along and make sure he is dead. He does not know he has been betrayed; the doctor will not live up to her agreement. We see him struggle impatiently with the pills, collapse in agonized frustration, his head striking the coffee table. He falls to the floor, his face smeared in blood and tears. Has he failed on purpose, thinking that death will come nonetheless? Or is it simply that he is no longer able to do what he needs to do? Spears’s Anthony writhed in pain and shame, abandoned, unable to live or die. All my sons, indeed.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: A Question of Mercy, All My Sons, American-Repertory-Theatre, Arthur Miller, BCAP, Boston, Bread and Puppet Theater, Clifford Odets, David-Rabe, Groundswell, Huntington-Theatre-Company, Jim Petosa, Lyric stage company of boston, Paradise Lost, Persona Non Grata, Relevance, Tear Open the Door of Heaven

The Moslem religion didn’t appear to be one of the targets, even though some of its adherents commit repression and murder in the name of righteousness, suggesting the convenient, knee-jerk partiality of the attack. The West and its allies are the all-purpose boogeymen — apparently not all the doors of heaven need to be kicked in.

It’s pretty standard for Schumann that anything that can be termed “the West” must be evil and anything that is opposed to “the West” must be good. In 2004 I was a fly on the wall in a conversation where he kept maintaining that Osama bin Laden was just a misunderstood anti-Imperialist and expressed his annoyance that his company unanimously refused to perform one of bin Laden’s texts.

But, what really amazes me is that after all these years, I still seem to be the only writer who has noted that the happy childhood of imaginative play and fresh-baked bread about which Schumann waxes nostalgically was under the Third Reich, or just how often he attempts to portray the Germans as the victims of WWII when he gives interviews.

As an artist, I still value everything I learned from working with him, but I’ve long ago concluded that his political content is best described as schizophrenic.

I admire your tenacity in your critique of Schumann, Ian, I know you’ve taken a lot of sh*t for it. I do think the group itself somewhat controls what I believe you accurately describe as an eccentric crypto-fascism lurking within all that crunchy anti-fascism.

As for the rest of Mr. Marx’s article, there are so many buried contradictions and unexamined assumptions in it that I don’t really know where to begin. (I may begin soon on my own blog, anyway.) But it does seem clear that what seems unthinkable to him is actually quite obvious to anyone who goes to the theatre regularly—today’s playwrights are not, actually, delivering a better picture of “the way we live now” than Arthur Miller does. The question is why. As Marx points out, the academy is churning out dozens, if not hundreds, of new playwrights every year. Yet almost every great playwright you can think of did not, in fact, go to a university program (the only one I can recall offhand who did is Sarah Kane). Yet Marx is so psychologically wedded to the academic-theatrical complex in its nostalgic, post-60’s mode that he can’t even begin to address that issue.

When Marx was being published in print or was being heard on the radio, he often bemoaned the fact that the column inches and air time devoted to criticism was shrinking. Now that he was all the bandwidth in the world, however, we rarely hear from him. Which may not be a bad thing, given how inaccurate his review of “Groundswell” is. And one does wonder what the point is of a review of “A Question of Mercy”—particularly when it’s a rave—when the show has been closed for several weeks. I’ve tangled with Marx before on just this question, of course—he has criticized me for writing enthusiastically (in “blurbs,” as I think he put it) about shows I thought the public should see, and yet at the same time (as here) he expresses sadness over slim houses for the new plays he thinks are important.

How is this double, contradictory consciousness possible, I wonder? How on the one hand can he bemoan small audiences for new work while at the same time making no effort to inform the public about that work? It’s truly bizarre. I myself didn’t catch “A Question of Mercy”—I gambled against it and saw something else, as I heard about it late (publicity was terrible). Yet it was widely discussed during the recent IRNE award conversations, and the IRNE critics who saw it—and wrote about it at the time—were insistent that it receive some nomination attention. Perhaps he could begin to take his cues from them.

Amid Garvey’s usual self-congratulatory snark an interesting point or two. I didn’t say playwrights couldn’t come from outside of the “academic-theatrical complex,” whatever that is. Garvey concludes (via his all-knowing intuition?) that no playwrights are delivering a better picture of “the way we live now” than Miller. Apparently, he has read all the scripts that theaters around the country have decided not to produce. (Yet his vaunted omniscience missed “A Question of Mercy.”) That kind of shrill absurdity, worthy of the demented monsters that live in his fantasy “academic-theatrical complex,” is worth pointing out.

(I do need to remind myself that my punctuation gets wonky when I post comments after midnight)

I admire your tenacity in your critique of Schumann, Ian, I know you’ve taken a lot of sh*t for it.

Thanks, it’s precisely because of Schumann’s stature on puppet theatre, and “radical” theatre (where some of my roots are) that a critique has to be made. He’s one of the vectors by which crypto-fascist, or, at least, fascist-sympathetic discourse has infected “the left.” I think that the handful of interviews where he himself links his anti-Israeli, anti-American, and anti-Western sentiments to his childhood rage at Germany losing WWII, pretty much solidifies it (that is, if trivialization of the Holocaust isn’t enough for you.) Let us not forget that the societies he does valorize are authoritarian, as well as violently anti-Semitic, misogynist, and homophobic (as we all seem to have realized.)

As far as the rage directed at me, the most articulate example was being yelled for five or six minutes while riding the CT2 between Sullivan Square and Union; it rarely rises above that level. Most writers on the topic of Bread and Puppet are either hagiographers, and are either in denial about Schumann’s real politics, or at least don’t want to spend enough time addressing my concerns for fear it may cost them access to their primary subject.

But hey, I’m not afraid to call a black-shirt a black-shirt, even when he wears white.

My one personal experience with Arthur Miller was directing the Washington DC area premiere of his under valued Broken Glass. Reading Bill’s take on Miller’s own articulation of the theatre’s relevance reminded me of his tenacity as a writer. How he kept at it and stayed available to collaborations! (He allowed our dramaturg to maintain a standing 5 p.m. telephone time to talk with us about any questions or thoughts that came out of the day’s rehearsal.) He was an unpretentious steward of his own work, and he relished the new opportunities that came with collaboration. I believe he attempted to live what he preached . . . to maintain his relevance by continuing to write, a task he did daily until his death.