Classical Music Review: ‘Turn of the Screw’

Reviewed By Caldwell Titcomb

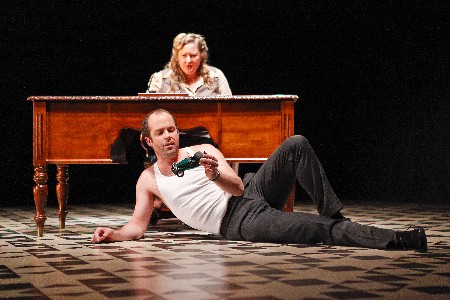

Quint (tenor Vale Rideout) and Miss Jessel (soprano Rebecca Nash) discuss their influence over the innocent children Flora and Miles (Photo Credit: Jeffrey Dunn)

The Boston Lyric Opera (BLO) initiated this week what it calls Opera Annex by moving out of its usual venue for its production of Benjamin Britten’s opera The Turn of the Screw. The site chosen was the Park Plaza Castle, built in 1891 as a Boston armory.

The BLO transformed the cavernous drill hall, setting up bleachers for an audience of 500. At stage left was a sizable, raised platform with a desk and a chair or two. At stage right was the specified orchestra of 13 players, with a narrow walkway in front of it. Above the orchestra was a large screen to accommodate a series of projections, flanked by a pair of monitors to carry the words of Myfanwy Piper’s libretto. All this, with one exception, worked surprisingly well. The space, which one thought might have too much reverberation, proved to be excellent acoustically.

The opera is based on Henry James’ tense and ghostly 1898 novella, in which a pair of young orphans (Miles and Flora) are tended to by a new governess who copes with the malevolent spirits of her predecessor (Miss Jessel) and a servant (Peter Quint), both dead. In the James tale the two ghosts do not speak; but, this being an opera, they sing—albeit ambiguously. James refused to clarify his story, and the work thus contains a number of questions that have no definite answers.

Britten composed the opera at great speed, starting in March of 1954 with the premiere set for September. Yet he came up with one of his strongest scores. An essential, he said, was “a firm and secure musical structure which can safely hold together and make sense of one’s wildest fantasies.”

To this end he chose a brief prologue and 15 scenes, each preceded by an orchestral interlude. These interludes were based on a row of all 12 pitches, but not in the way that Schoenberg and the serialists adopted. Britten’s row was a set of six pairs of perfect-fifth intervals. This means that, for all the music’s dissonance, Britten was operating within the system of tonalities.

The director, Sam Helfrich, decided to adopt modern dress for this show. I would have preferred to see the production set in the mid-19th century where James put it, but this is a minor quibble. My chief reservation concerns the video projections by Leah Gelpe, some full-screen and some split-screen. So we saw Miles tossing basketballs and we watched Quint and Miss Jessel making love on a bed—these were just distracting when the work itself needs no such embellishments.

The Governess (soprano Emily Pulley) enjoys a tranquil evening on the grounds of Bly, her new home (Photo Credit: Jeffery Dunn)

The BLO came up with a strong cast of six singers. Soprano Emily Pulley as The Governess was a powerhouse with varying emotions as she sought unsuccesfully to protect her two charges from corruption. Mezzo-soprano Joyce Castle, reprising a role she has done elsewhere, provided a solid portrayal of the elderly housekeeper, Mrs. Grose. Tenor Vale Rideout was an admirable, unshaven Quint, proclaiming, “I’m all things strange and bold.” As Miss Jessel, soprano Rebecca Nash was a bit wobbly in pitch at first, but fine once she warmed up. Soprano Kathryn Skemp did well as the orphaned daughter, Flora.

Miles calls for a boy soprano—the demanding role was originated by 12-year-old David Hemmings, who would go on to a notable career in the movies. Here the part was adroitly taken by 13-year-old Aidan Gent (alternating at other performances with 12-year-old Ryan Williams).

Conductor Andrew Bisantz elicited precise playing from his chamber orchestra, so superbly scored by Britten—especially in his menacing use of the timpani. One hopes that the BLO’s Opera Annex project will continue in future seasons.

Tagged: Andrew Bisantz, Benjamin Britten, Boston-Lyric-Opera, Caldwell-Titcomb, Henry James, Opera, Opera Annex