Book Commentary: Machado De Assis — Genius at 100

by Bill Marx

“If Borges is the writer who made Garcia Marquez possible,” observed Salman Rushdie, “then it is no exaggeration to say that Machado de Assis is the writer who made Borges possible.” Rushdie’s piggybacked history of the hemisphere’s premier intellectual ironists is correct but, at least until the last decade or so, Machado was a neglected progenitor, his finest novels hailed by a relatively small circle of discerning readers who wondered why the gargantuan achievement of the Brazilian writer wasn’t recognized.

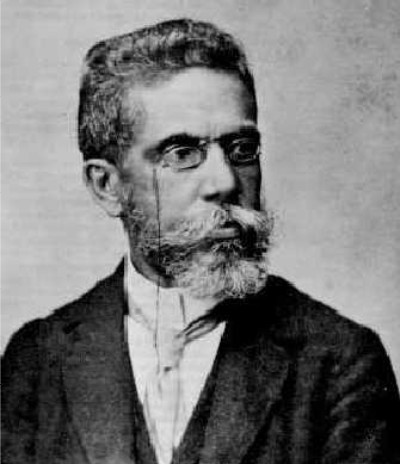

Brazilian Machado de Assis, more modern than most modern writers

The celebrations and symposium around the world dedicated to Machado on the 100th anniversary of his death (September 29) suggest that he is finally getting his due – he is a writer who remains more contemporary than many of our so-called moderns.

Not only is Machado the first great Latin American novelist – his fiction plays a crucial role in the development of modern literature. Though written in the late 19th century, the novels of Machado venture into postmodernism before it became fashionable. And he is much more wickedly entertaining than the innovators who followed him, partly because he loves to toy with — rather than radically break down – staid realist conventions. Machado’s brilliance lies in his deft combination of distanced irony with intimations of encroaching darkness, self-reflexive antics that kick around bits of the soul.

His 1880 masterpiece The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas is made up of the writings of the title character after he is dead and buried. The novel is a fierce satire of egotism masquerading as a breezy meditation on life and afterlife by a member of Brazil’s pampered upper crust. Cubas reverses traditional narrative expectations (he starts his reminiscences with his death before proceeding to his birth) and addresses the reader at the drop of a whim. The book’s chapters range from three to four pages to a sentence. The chapter, “How I Didn’t Get to Be Minister of States,” is left blank. My favorite section is entitled, “To a Critic,” where Cubas, feeling he isn’t being understood, launches into the plea of all authors: “Good Lord! Do I have to explain everything?”

Eventually, for all his wit and dazzle, Cubas becomes trapped in his obsessions: his dream of creating a poultice for melancholia kills him; his romantic escapades, rich in revelations of the character’s neediness, are also exercises in solipsistic farce. Cubas is a ghost crawling around the edges of his skull, thinking his chuckles and charm will distract us from the emptiness.

Published in 1900, Dom Casmurro boasts one of the most delightfully puzzling female characters in 19th century fiction, Capitu, a woman who takes the narrator, Bento, to the heights of love and the depths of doubt. The crux of the book is a powerful depiction of jealousy crossing into near-dementia. Bento becomes convinced his son was the offspring of a supposed love affair between Capitu and his diseased best friend, Escobar.

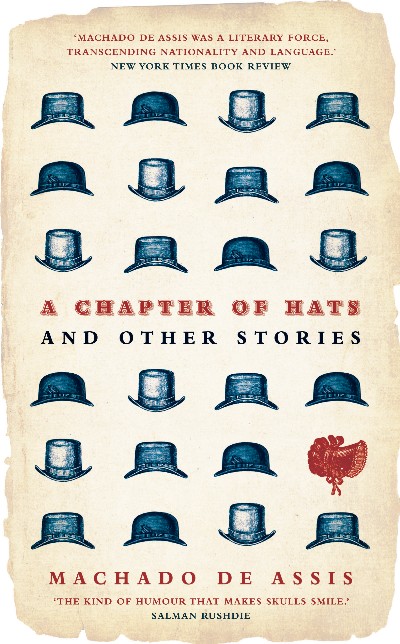

Other Machado marvels include Quincas Borba, a sparklingly sadistic satire of a dog who may be channeling the soul of a mad dead philosopher. De Assis also wrote a number of short stories, many marked by the Swiftian whimsy found in his acclaimed novels. John Gledson, a respected British authority on Machado, has just published a collection of newly translated tales, A Chapter of Hats: Selected Stories, which will provide a splendid introduction to the writer.

Why has it taken so long for Machado to become as well known here as Borges or Marquez? In the 1950s and 60s Helen Caldwell and William Grossman translated the best of his fiction into English; these efforts were enthusiastically received by reviewers, including V.S. Pritchett and Elizabeth Hardwick. Among contemporary critics, John Barth and the late Susan Sontag are fans of Machado. But when the Latin American literary boom boomed across American campuses in the 1970s, lazy readers, gorging on diets of Marquez and Llosa, never adventured back in time further than three or four decades.

Perhaps the problem is that the remarkable playfulness of Machado’s fiction works against him. He is difficult to classify: romantic and realist, idealistic and cynical, rational and cranky. His life includes extremes as well: a mulatto who received little formal education, Machado was a shy epileptic who became president of Brazil’s Academy of letters and received a state funeral when he died in 1908.

Some critics complain about the quality of the early translations from the Portuguese, but over the past decade or so most of Machado’s major novels have received new translations, many are from Oxford University Press, which called on the impressive talents of Gregory Rabassa and John Gledson. There are no longer any excuses to ignore the Brazilian master of seriocomic wonder.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

this is a very good introduction to our most important writer, Machado de Assis. Thank you.

Roselis Batista R.

Université de Reims champagne Ardenne

France