Theater Review: Gloucester Stage Company Tries The Impossible

Now why, you might ask. Why is there no reaction? Why does everyone involved choose to ignore the scandal? Because, playwright Alan Ayckbourn would say, that is how most of us are. To paraphrase Hamlet, we rather bear the troubles we know, than—by opposing them—create even bigger ones.

Living Together by Alan Ayckbourn. Directed by Eric Engel. At the Gloucester Stage, Gloucester, MA, through June 26.

By Peter-Adrian Cohen

You have to hand it to director Eric Engel and his ensemble; they have not only tackled a challenging comedy but a British one at that, and not just any comedy—the extra difficult kind that does not come with a particularly inventive plot (as some other Ayckbourn plays do) or an abundance of wit (of the sort that keeps us chuckling through an Oscar Wilde play). Instead, what the dramatist gives the actors and director is two acts that seem to merely record an awkward kind of dance involving three dysfunctional couples.

You might almost think of a soap opera. But there is a difference. And that difference is that what you hear is of an absolutely irritating passivity. Ayckbourn’s characters not only see the world this way, even more irritatingly, they talk about it like that. Normal people do their best to disguise their real motives, especially when they are scandalous, but unconscious behavior and emotional revelations give their game away. In this play it’s the opposite: The character of Norman, for example, seduces sequentially his wife’s sister, her other sister, and finally even the wife herself—without any lasting reaction to speak of.

Now why, you might ask. Why is there no reaction? Why does everyone involved, choose to ignore the scandal? Because, Ayckbourn would say, that is how most of us are. To paraphrase Hamlet, we rather bear the troubles we know, than—by opposing them—create even bigger ones.

So what comes across as apparently simple-minded dialogue is, in fact, utterly unbearable, so unbearable that even the characters themselves cannot simply laugh it off. In Ayckbourn’s play we see ourselves as we try, at all cost, not to. And that clearly goes beyond soap opera and beyond what is usually served to us a comedy. In fact, Ayckbourn’s comedies—and Living Together in particular—have little do with comedy; they are tragedies in disguise.

And therein lies the difficulty of presenting Living Together. We’re dealing with a kind of comedy that is more strange than funny, with nothing really to laugh about. Now don’t get me wrong—the audience does get to laugh. And there are witty lines—but more in the manner of comic relief, such as would befit a tragedy.

Faced with this difficulty, what does a director do? What does an ensemble do?

For one thing, they focus not on the lines—there is little to focus on there. They focus on the way the lines are delivered. On timing. And on the one thing that makes these characters funny: that they don’t know they are. On the earnestness with which they insist on their mistakes.

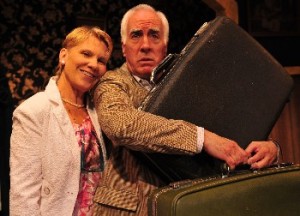

LIVING TOGETHER — Fun and games: Sarah Newhouse as Annie; Lindsay Crouse as Sarah, Barlow Adamson as Tom and Richard Snee as Reg. Photo: Gary Ng

Now the problem with the above approach is that working this way requires extra and still extra amounts of rehearsing. If a tragedy can be done with three weeks of rehearsal, a comedy will require six. This is time that smaller theaters like Gloucester Stage don’t have (or if they have the time, they don’t have the money).

And it isn’t just honing the delivery that requires extra time; it’s that in a comedy like Ayckbourn’s, the author supplies not fleshed-out characters but stick figures. They come from nowhere, have no history, and vanish into thin air at the end of the performance. But precisely because of that, each actor has to invent and build a stock persona, a stock set of gestures that flesh out his delivery and make his character three-dimensional. And that, again, requires extra time.

I trust you now understand what I meant above when I said that Engel and his ensemble have done what is hardest: They have dared to stage a comedy—and a highly sophisticated one at that.

If you go and see it, which I recommend, you will delight in the accomplished cast (Barlow Adamson, Steven Barkhimer, Lindsay Crouse, Jennie Israel, Sarah Newhouse, and Richard Snee). But Jennie Israel (as Ruth) comes closest to having built a truly comic character and delivers some especially hilarious moments.

So when I finally say that this production—in spite of its obvious strengths—does not fully succeed, it is not because anyone has failed to do their job. It’s simply that actors and director have tried the impossible. And for that alone, they deserve our applause.