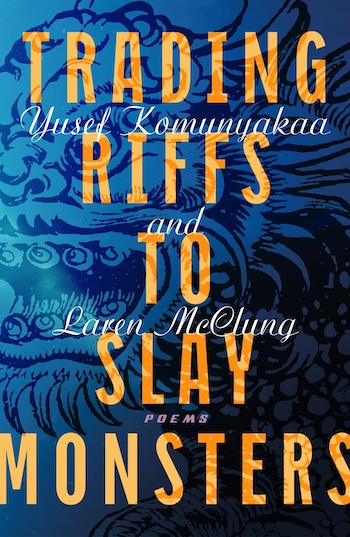

Poetry Review: “Trading Riffs to Slay Monsters” — Song of Pain and Praise

By Michael Londra

Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung’s goal — achieved through tag-team lyric utterance — is a noble spirituality.

Trading Riffs to Slay Monsters by Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 240 pp, $22

In February 2020, a month before coronavirus officially shook the world, I was visiting San Francisco. My wife and I had flown in for a writers’ conference. She was going to be busy with panel discussions while I took in the sights. A rabid bibliophile, I worshipped at the City Lights bookstore and the Beat Museum, then saluted the Robert Frost Memorial Plaque. Meanwhile, bulletins about a cruise ship off Japan’s coastline with infected passengers pinged my iPhone. I am not a glass-half-empty type of person; I am a there’s-no-glass-to-begin-with-and-the-water-is-all-over-the-floor-rising-up-to-our-knees-soon-to-reach-our-mouths-and-drown-us paranoiac. Instinctively, I started to withdraw in public — exercising what would later be called “social distancing.” On our return flight to New York, people coughed loudly. Soon after, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 60 Covid cases across 12 states. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic had arrived.

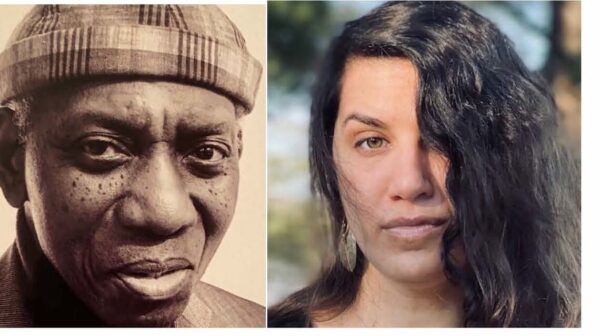

Today, I consider my dread back then as quaint, almost prelapsarian. We had no inkling of the pervasive evil that was coming. Pulitzer Prize–winner Yusef Komunyakaa and New York University writing professor Laren McClung’s collaboratively-composed epic poem, Trading Riffs to Slay Monsters, emerges out of the depths of that global health emergency. The poem interweaves elegy and lament in a duet that’s composed of alternately written three-line stanzas called tercets—reminiscent of Dante’s Commedia. The project was begun by Komunyakaa in an email exchange with McClung. The result is a book-length meditation on history, memory, music, and the city of New York — while a ravenous plague is on the loose.

At first blush, such a conceit might seem antithetical to “authentic” poetic expression. Isn’t a poem supposed to be the sole product of a single mind? Truth is, verse-making has a long and distinguished team sport pedigree. Homer’s name, for instance, is just a catch-all for the Greek oral tradition. Additional examples: André Breton and Paul Éluard’s The Immaculate Conception (1930); Charles Henri Ford’s “International Chainpoem” (1940) with 11 other contributors; John Ashbery and Kenneth Koch’s “New Year’s Eve” (1961); Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Neal Cassady’s “Pull My Daisy” (1949); and Oyl (2000), Denise Duhamel and Maureen Seaton’s tribute to Popeye’s beloved Olive.

Trading Riffs to Slay Monsters eliminates any anxiety as to who wrote what. The book’s formatting places Komunyakaa’s tercets first, justified left. McClung’s sit underneath them, indented. The effect is like driving at night — a steady meditative rhythm rolling forward with relentless momentum. At a certain point, the reader doesn’t care who’s talking. This successful blending of tone and cadence transcends conventional claims about the mystique of individuality. But it has its limitations.

Komunyakaa credits John Coltrane as the volume’s reigning tutelary deity. In his preface, he writes that one morning “with the fear of Covid on me, I had awakened with these words on my tongue ‘Trading Riffs to Slay Monsters’… listening hours to John Coltrane’s My Favorite Things.… Coltrane was a monster — a genius in search of soulful perfection.” The poetry here was meant to be like improvisational jazz: “a method of … surviving through grace.” True to this mission, McClung does her part to set the stage with a montage of life under lockdown: “New Yorkers ride a storm in the heart / from Jackson Heights to Coney Island, // Harlem to the Rockaways … rhythm of trains a steady heartbeat / against immense silence where grief resides.” But Coltrane parsed his long-form suites into labeled harmonic segments. A Love Supreme was broken into four parts: “Acknowledgement,” “Resolution,” “Pursuance,” and “Psalm.” The riffs in this volume are unnumbered and not divided into manageable sections. The immersive Coltrane-inspired “sheets of sound” (as critic Ira Gitler once described Trane’s late-’50s improvisational technique) is compelling, but some notational system would have been useful to assist the reader’s comprehension of the poem’s development — even Dante had cantos.

Poets Yusef Komunyakaa and Laren McClung. Photo: PoetryFoundation.org

History is the muse for these poets: “Time can be a monster.” The Black Death in Europe in 1347 and 1918’s influenza outbreak are essential reference points. Important figures and artists are also evoked: Houdini; John and Yoko; Baudelaire; Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat; Al Capone; Mary Todd Lincoln; Marcus Aurelius, among others. Toni Morrison is also charmingly summoned: “I see Toni, a Saturday evening in D.C. … she told us Brando once called / to read her passages from Song of Solomon.” And victims of domestic terror are memorialized: “George Floyd’s death … a personal vendetta … caught by a brave girl’s cellphone;” and “how far is it / from where they shot Ahmaud Arbery / in early light.” An ode to Ruth Bader Ginsburg is especially euphonious: “Notorious RBG knew how to … choose each word surgically, slowly, & precise as some lover’s aria.”

Key words link the tercets. A chain of associations accumulates into a surfeit of reflections on our shared human condition — from antiquity to premonitions of the future. A few offbeat asides pop up among the major points: “Edmonia shaped marble // into silk so fine Cleopatra’s nipple reveals / through her gown.” Fascinating etymological glosses are also aired: “get a handle on the Greek / word, pathos, path, & we navigate // pathologies from Latin passus, passion.” Instances of eye-catching enjambments abound: “Picture Orson Welles at the Federal … directing a rendition of the Bard’s play, Voodoo / Macbeth.” The poets’ age difference is occasionally referenced, but overall the verse strives for an eternal present that sloughs off such petty vanities. Sonorous language is the only relevant lingua franca: “We lament destinies / scribed on sand / by the sea’s unforgiving agitation / forged in a wind’s lonely probe.”

Trading Riffs to Slay Monsters is a long song of pain and praise. Death in its myriad incarnations is acknowledged, but there is a stubborn refusal to bow to mortality’s bullying. Komunyakaa and McClung’s goal — achieved through tag team lyric utterance — is a noble spirituality. Its optimistic temper is best exemplified in these lines, a tercet suggesting that poetry’s redemptive choral uplift can slay any foe. All we need do, it turns out, is to stay in tempo: “Life, damn you, straight out of bittersweet Big Apple, / we’re all tangled up inside our singing or blind calling / to a blood moon, but I’m patting my feet, still in tune.”

Michael Londra — poet, fiction writer, critic — talks New York writers in the YouTube indie doc Only the Dead Know Brooklyn (dir. Barbara Glasser, 2022). His poetry has been translated into Chinese by poet-scholar Yongbo Ma. Two of his Asian Review of Books contributions have been named to the publication’s list of Highlights of the Year for 2024 and 2025. His Arts Fuse review “Life in a State of Sparkle—The Writings of David Shapiro” was selected for the Best American Poetry blog. “Time Is the Fire,” the prologue to his soon-completed Delmore&Lou: A Novel of Delmore Schwartz and Lou Reed, appears in DarkWinter Literary Magazine. He can also be found in Restless Messengers, The Fortnightly Review, spoKe, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, and The Blue Mountain Review, among others. Born in New York City, he lives in Manhattan.