Jazz Commentary: The Enduring Enigma of Chet Baker

By Steve Provizer

I take a look back at the compelling documentary Let’s Get Lost because of the recently released Chet Baker Performs and Sings: Swimming by Moonlight, 15 unreleased studio recordings made by the trumpeter.

I admit to a small obsession with trumpeter Chet Baker. I’ve written a lot about him, exploring the fact that he changed the permissible boundary of vulnerability in male singing and created a congruent, convincing voice on trumpet. All the while, trying to understand how such compelling music could emerge from a drug-besotted, narcissistic, and incontestably charismatic personality.

I admit to a small obsession with trumpeter Chet Baker. I’ve written a lot about him, exploring the fact that he changed the permissible boundary of vulnerability in male singing and created a congruent, convincing voice on trumpet. All the while, trying to understand how such compelling music could emerge from a drug-besotted, narcissistic, and incontestably charismatic personality.

The 1988 film Let’s Get Lost essentially explores the same territory. The level of obsession that compelled Bruce Weber to bring this documentary into the world dwarfs my own, but his approach to Baker suggests that we both believe that drawing conclusions or “lessons” from his life is reductive. Let’s Get Lost maintains a remarkably neutral focus, portraying Baker as simultaneously magnetic, repulsive, needy, aloof, and musically sui generis. Weber’s choice to shoot in high contrast 16mm black-and-white film, a palette both gritty and dreamlike, provides a perfect visual analogue to his vision of Baker.

I revisit this film now because of the recently released Chet Baker Performs and Sings: Swimming by Moonlight, 15 unreleased studio recordings made by Baker. Weber and his co-producer, wife Nan Bush, conceived the idea of filming a recording session for the documentary. This is the source of almost all the tracks.

Baker’s capable collaborators on these recordings are Frank Strazzeri on piano, John Leftwich on bass (he also produced this release), Ralph Penland on drums, and Nicola Stilo on guitar and flute. Hubert Laws overdubs flute on “Quiet Nights.” Most of the repertoire is made up of songs listeners associate with Baker, including, “Remember,” “Relaxin’,” “I’ll Be Around,” and “Just Friends.” He recites the lyrics of “Deep in a Dream” with no music. Other tracks are less familiar, including ”Make Me Rainbows,” “Arbor Way,” and “Milestones.” The final track, which plays an important part in the film is “Almost Blue,” an Elvis Costello tune. Some of the tracks have been, to my ear, over-processed with reverb, and the electric DX-7 can sound a little archaic. Overall, though, it’s very satisfying music.

The recordings are “late period” Chet Baker, recorded in 1987, only a year before he died. As such, they represent a continuation or accentuation of certain musical elements and a slight diminution of others. His sweetly astringent tone remains immediately recognizable. That includes both his trumpet and flugelhorn tone and his voice. His scatting remains strong and his vocal range is intact. His improvisations on horn are somewhat more stripped down, with increased space and fewer extended, articulated lines — though on tracks like “Milestones” he occasionally still delivers. He remains a peerless player of melody.

A number of other recordings made in this session were deftly used in the soundtrack of the film, to comment on and/or underscore the action. We are also presented with a lot of film footage of the recording session. Under the opening credits, we hear a conversation in which Baker is clearly frustrated at getting the recording started. The tune “Almost Blue” begins, and we see Baker’s hyper intimate relationship with the microphone — if it were any closer, as Groucho Marx might say, it would be behind him. In the background, we see the people who have been collected to serve as Baker’s “posse” for much of the filming: Flea, bass player for the Hot Chili Peppers, pop musician Chris Isaak, model-actress Lisa Marie (featured in Weber’s Calvin Klein Obsession campaign), and Diane Vavra, Baker’s then-girlfriend.

Apart from what Weber shot for the film, there’s extensive archival photography, including film and television footage, much of it from Baker’s time in Italy. These elements are deftly woven together: one never feels that too much time has been spent with one element at the expense of another. The best way I can illustrate this balance is by noting each segment, even if very briefly.

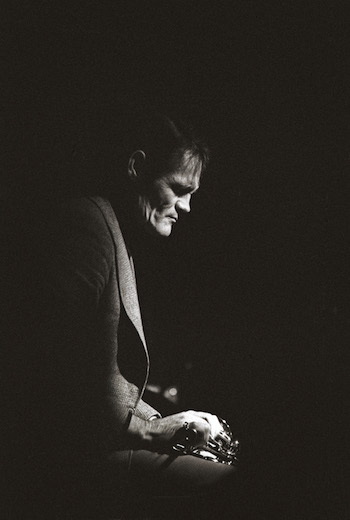

Trumpeter and vocalist Chet Baker. Photo: Michael Ullman

Much of the beginning of the film has Baker on the beach, in cars and restaurants, cavorting and canoodling with his group, which clearly idolizes him. We see beauty shots of L.A. palm trees while Weber in voice-over talks about the obsession he had with Baker and how he discovered the same obsession was held by the woman who would become his wife, Nan Bush. These visuals of Baker’s youth and beauty are not crudely juxtaposed with the trumpeter’s lined, aging face, but the contrast lingers in the mind.

Jeff Preiss was the director of photography. He worked with Weber on his other documentaries. I was not surprised to hear that Preiss’s outfit Epoch produced Low Down, a biopic based on the life of jazz pianist Joe Albany, which draws on a very similar black-and-white palette. The free-floating nostalgia evoked by Let’s Get Lost‘s cinematography comes to ground when photographer William Claxton talks about shooting Baker at a 1954 recording session. A montage dramatizes a hand choosing photos from contact sheets of that session. Claxton tells us how photogenic and charismatic Chet was — he always had great ladies and great cars.

Then the doc returns to a slightly starker present. We see Baker walking slowly on the balcony of his hotel room, warming up on his trumpet, then packing it up and checking out how he looks before he goes to the gig. We cut to old TV footage of young Baker in San Remo in 1956 and then back to him, now in close-up. The sense of how lonely life can be on the road is palpable.

We continue following the arc of Baker’s early days from Dick Bock, founder of Pacific Records, who talks about Chet’s triumph in Gerry Mulligan’s group. The producer tells a nifty story of how Red Norvo was responsible for making Mulligan’s a pianoless quartet. Bock says Baker smoked pot at the time, but was not yet a heroin user.

After this comes the first segment of an interview Baker had with Weber, who remains off camera. The conversation will be cut into the film at several points. The talk gives us Baker at his lowest — he looks bad. He talks about drugs, but the question of whether or not he is high during the interview is dealt with ambiguously. We hear that “he hasn’t got what he needed,” but don’t learn whether that’s heroin or methadone and whether or not he scored. He seems pretty stoned to me.

We see Baker appearing in 1968 on The Steve Allen Show. The very funny trumpeter Jack Sheldon then talks about the pair’s shared history. The stories are amusing, but mark the first signs of the narcissistic, self-serving side of Baker’s personality. This is followed up with an interview featuring an old girlfriend, Joyce Night Tucker, who reinforces this more critical perspective on Baker’s personality.

Baker’s first exposure to jazz was swing; hearing Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie for the first time left him stunned. I have the sense that if Baker ever really felt he needed to practice, it was when he knew he had to catch up with the beboppers. Bass player John Leftwich points out that some NYC jazz musicians unfairly put down West Coast practitioners.

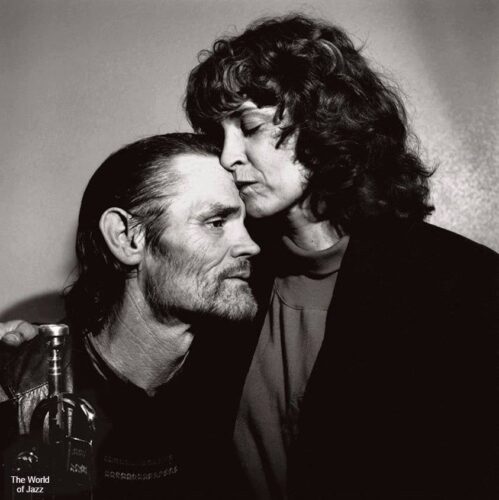

Then Diane Vavra offers further insight into Baker’s “Jekyll and Hyde” personality. She says she fell in love with him immediately but, because of events she doesn’t describe on camera, she ended up in a women’s shelter. Chet elicits sympathy, she says, but it’s a big act. I was amazed at how she was so willing to bad-mouth Baker on camera, especially after we’ve just been given footage of the two of them making out in a car. Weber then wryly includes shots of them close dancing to “Every Time We Say Goodbye.”

The doc goes back to Sheldon, who tells us what a natural musician “Chettie” was: “It was real easy for him, and I hated that I had to practice, he never had to.” These two musicians circled each other, like planets in an eccentric orbit, their entire lives.

Baker tells the interesting story of how he got out of the army. It entailed manipulating what were then seen as links between mental illness and homosexuality. The tricky part, Baker says, was evading both the draft and involuntary shock treatment.

Chet Baker with Diane Vavra. Photo: Richard Dumas

Baker was in several films, and we now see a clip from Hell’s Horizon. He plays a trumpeter, of course. At one point, the trumpet has to really blare. I bet the director dubbed that in. It’s not a sound Baker ever made on a trumpet.

At this point, we go to Oklahoma and are introduced to Baker’s family, a group one can imagine having been photographed by Dorothea Lange in the ’30s. Unlike previous high-contrast visuals, these scenes are rendered as a soft wash of light, with little contrast. The camera lingers on the trumpeter’s “baby book” as his mother Vera recalls Chet’s closeness to her, and recounts the story of his father buying him a trumpet. A contradictory version of this same story is later told by the musician himself. Baker was, as is to be expected, a prodigy. We pan around some of Baker’s musical awards and see how proud Vera is of him. Then, Weber asks if Chet disappointed her as a son. Her response: “Yes, but let’s not go into that.”

Later in the film, we see two of Baker’s three sons and daughter with their mother, Baker’s second ex-wife, Carol. There is no sense that he spent much time with his family, and what we get from them onscreen is a combination of frustration, resentment, and yet, a shred of pride. Carol tells us she was working in a follies and met Baker in Milan. We see period photos. Later on, we hear about Baker having his teeth knocked out; Carol tells us that she stuck with him through very rough times. Eventually, Baker started to gig again and, in 1975, he went to work in Europe. While he was there, his son Dean was hit by a car. Carol insists that Baker never responded to her phone calls. She blames the demise of their marriage on a woman who is introduced later in the movie, Ruth Young. To put it mildly, Baker’s exes are not very positively disposed toward each other.

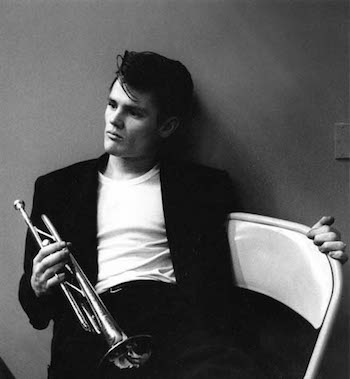

Young Chet Baker. Photo: JazzLabels

Lawrence Trimble, screenwriter and actor, sets Baker in a broader cultural perspective. He ruminates on the cultural influence of antiheroes in the ’50s. We see clips from the film All the Fine Young Cannibals with Robert Wagner ostensibly representing Baker. The trumpet playing in the movie (ghosted by Uan Rasey) bears about as much resemblance to Baker’s as Kirk Douglas’s does to Bix Beiderbecke’s in Young Man With a Horn (ghosted by Harry James). Trimble talks about seeing Baker in Paris, particularly the wide romantic swath he cut. There’s nice footage of Bud Powell and of Andy Bey and the Bey Sisters.

At this point in the film, Baker is asked what the best day of his life was: ”Maybe the day I got my Alfa Romeo SS.”

Now, the topic of his teeth. It’s well known that in 1966, Baker’s teeth were knocked out, requiring dentures and a painstaking rebuilding of his embouchure. The trumpeter supplies a detailed version of how it happened; it involved a drug deal, “5 black cats,” and a white car driver who wouldn’t let him in the car so Baker could get away from his assailants.

Next, we’re introduced to an ex-girlfriend, Ruth Young, who talks about falling for Baker. When she met him for the first time at a gig, he looked gaunt and horrible, she says, but “he was still my hero. He was trying so hard but played like shit.” She says he drained her of most of her money and that his version of how he lost his tooth is baloney.

Let’s Get Lost, at this point, moves between Italy, Oklahoma, and Cannes.

In an Italian movie, Urlatura al Sbarri, we see Chet in a bathtub with his horn. Then there’s a look at Chet singing on Italian TV. We learn of his arrest in Lucca, Italy, where he was living in “a clinic.” He told one version of what happened; the Italian newspapers told another. Baker ended up serving 15 months in prison.

We return to Oklahoma and, with “Blame It on My Youth” on the soundtrack, and a very slow pan we see his kids and Carol and his mom simply looking at the camera. Again, nothing happens in the shot, but the moment stays with you.

The only child Baker discusses extensively is his son, Chesney, from his first marriage to Halema Ali. Baker sings a song he wrote about Chesney — then we hear the instrumental version. Chesney is the only child thanked in the closing credits, apparently because he gave the filmmakers access to some photos. Baker says, “I tried to instill in them a good way to go in this life is to find something that you really enjoy doing and then learn to do it better than anybody.” We go back to Oklahoma, and hear the kids say goodbye and only half-jokingly say, “we need some financial help, dad.”

Before the movie closes, there are some upbeat scenes. We go back to the convertible with Baker and Diane, then the whole gang frolicking on the beach. On the soundtrack, Baker talks about getting a piano and writing some tunes. Then he laments how so many of his friends have died in the last 10 years — Haig, Desmond, Farrell, Stitt, Pepper, and Zoot.

The doc cuts back to the interview with Weber, who asks Baker what his favorite high is. He says it’s “the kind of high that scares other people to death. I guess they call it a Speedball. It’s a mixture of cocaine and heroin. Get the right mixture — not too much coke…”

We go to Cannes, 1987. We don’t know this from the film, but research informs me that they were at the festival to present Weber’s debut film Broken Noses. Baker and Vavras are surrounded by photographers and reporters — the pair are having a ball. Baker starts to sing “Just Friends” with a guitarist who wanders onto the scene. Then comes vintage footage from earlier Cannes festivals; we see the likes of Yves Montand, Alfred Hitchcock, and Orson Welles. I’m not sure why.

Trumpeter and vocalist Chet Baker in his later years. Photo: Bandcamp

The final scene shot for the film is at the Casino in Cannes. I assume Weber had asked Baker to perform. The room is loud, and Baker remarks that the audience couldn’t care less about the music. He says he needs some cigarettes, and asks the audience to be quiet. It does quiet down, increasingly so, as he sings “Almost Blue.” The camera remains fixed on Baker throughout, motionless, in a single, close-up take.

A graphic comes up in black about Baker’s fatal fall from a hotel window in Amsterdam at the age of 59. It says the police found the body of a 30 year-old man. That’s odd. Given the wear and tear on Baker’s body, it should have been seen as the body of a much older man, not a much younger one. The graphic omits that traces of heroin and cocaine were later found in Baker’s body and room.

The closing credits roll over another of the trumpeter’s Italian movies. He sings the song “Arrivederci” and makes out with a girl in a park. The film ends with a kiss and the sound of a dog barking in the background.

Let’s Get Lost reminds us of the power of music. It confronts us directly with a man who is self-serving and self-destructive. And yet, when we hear Baker play and sing, the sound draws us into the moment. Our judgments of him and his behavior reappear only after the music fades.

I met Baker in about 1980 in a club in Washington, DC, called the One Step Down. He seemed frail but, when I approached him, he became animated and affable, ushering me over to his table, eager that I become a part of that night’s ad hoc posse.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: "Chet Baker Performs and Sings: Swimming by Moonlight", "Let's Get Lost", Bruce Weber, Chet Baker

I think any Chet Baker fan needs to watch “Let’s Get Lost” if only to highlight the contrast between the sweetness of Chet’s music and the sour quality of his personality. The eternal question: can you overlook the bad things about an artist and still enjoy their art?

Yes, always a question. I discuss it here, if you’re interested–https://artsfuse.org/246781/arts-commentary-separating-the-maker-from-the-made-the-doer-from-the-doing/

Of course you can–or you’re not going to enjoy much art. Most artists were objectionable in one way or another. As WH Gass wrote: “We read the classics because their authors are such fine upstanding people. [Irony, of course] Their authors are murderers, thieves, traitors, misogynists, sadists, liars, lowlifes resentful of any success, vicious gossips, gamblers, addicts, ass-lickers, sots, womanizers.” Etc. Be that as it may, Let’s Get Lost is a very fine documentary and my introduction to Baker.

Great piece, and I also love that documentary. One part which sticks out for me is when someone (I think it was an ex?) said that Baker could have been singing about paper towels or whatever, he wasn’t nearly as romantic as his music. Definitely the kind of person you wouldn’t want to lend money to.

Maybe the question isn’t so much about the great artists being morally great people (Gass is certainly right to point this out) but about their work being morally compelling in some way.

A morally bad person can know or at least imagine what the good is and nevertheless do bad things for any number of reasons. And vice versa. I don’t think they’re mutually exclusive.

So even if ultimately Chet Baker’s greatest love of his life was shooting smack that lovely, ethereal, seductive music suggests that he must have at the very least imagined what it would be like to have genuine human feelings.

There seems to be some confusion re: morals & feelings. Because one has feelings, and everyone does, doesn’t mean one has admirable morals.

Thanks, Matt. What you suggest is exactly the way actors proceed. No matter how foul a character’s behavior may be, there’s always something else at play. You have to find it (even if you have no chance to express it in dialogue).

Why do many, possibly most people want to project certain moral values onto the artists whose work moves them? Complex. Something about what art is supposed to “mean.” Something about not wanting to be judged oneself. For many people, separating the artist from the art is tantamount to separating themselves from the art.