Concert Review: “Inspiración” – The BSO Celebrates Puerto Rico with the Orquesta Sinfónico de Puerto Rico, and Re-celebrates James Carter with Dima Slobodeniouk

By Steve Elman

Concerts in the past week by the Boston Symphony Orchestra with guest artist James Carter and the Orquesta Sinfónico de Puerto Rico with guest artist Luis Sanz were a cultural festival and a musical feast.

Composer Tania León introduces Time to Time onstage at Symphony Hall on Thursday November 13. Photo: Michael J. Lutch, courtesy of the Boston Symphony Orchestra

The Boston Symphony is celebrating American diversity this season, although promotion for it has been rather low-key. The whole city should be aware of what the orchestra is calling “E Pluribus Unum: From Many, One” – a survey of the many voices that comprise American Music.

Puerto Rico is part of that landscape; it’s as American as salsa – the music, not the condiment. Just as Cuba and Mexico have contributed vitally to American culture (and as Ireland, Italy, Germany, and other major sources of immigration have done in the past), Puerto Rico has given Americans artistic joy for decades. It didn’t just start with Bad Bunny, thank you very much.

And, whether or not some people like the fact, unlike the foreign countries that have contributed so much to the American mainstream, Puerto Rico is a part of America.

So the first-ever concert in Boston by the Orquesta Sinfónico de Puerto Rico, on Friday November 14, was a cultural event that brought out a Symphony-Hall-ful of people of Puerto Rican ancestry and people who love its culture, along with a smattering of BSO regulars intrigued by the prospect.

On stage was Dr. Vanessa Calderón-Rosado, Chief Executive Officer of Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción (IBA), the Boston community development corporation that was instrumental in bringing the Orquesta here, who provided a heartfelt introduction to the program.

There, of course, was my old friend and WBUR stablemate José Massó, dap as ever and greeting fans and friends throughout the hall, riding fifty-plus years of hosting “Con Salsa,” his Afro-Latino music / spoken-word show on WBUR, and looking great, despite his three bouts with cancer.

And all around the hall were little Puerto Rican flags in the hands of many audience members, waved whenever the music took a familiar turn.

Also there, impressively, was Chad Smith, President and Chief Executive Officer of the BSO, who gave an impromptu introduction on stage to the concert and to Dr. Calderón-Rosado, showing great enthusiasm for the event and great respect to his guests. This did not represent a backhanded compliment to a provincial orchestra from out of town; his presence and sincerity were recognitions for a musical organization on a level worthy of comparison with his own orchestra.

And this band can play. The program, selected and conducted by the Orquesta’s music director Maximiliano Valdés, carefully combined elements of Puerto Rican vintage and contemporary classical music in the first half and a sort of Puerto Rican Pops program in the second. That Pops program was enhanced by the brilliant addition of cuatro virtuoso Luis Sanz and the Orquesta’s Associate Conductor, Rafael Enrique Irizarry, who led three works with familiar melodies. In effect, it was an OSPR season in miniature. It was akin to the idea of the BSO traveling to a city it had never before visited, bringing along single movements of some of its greatest hits for the first half of a concert and a selection of its most enjoyable Pops pieces for the second – with Andris Nelsons and Keith Lockhart conducting.

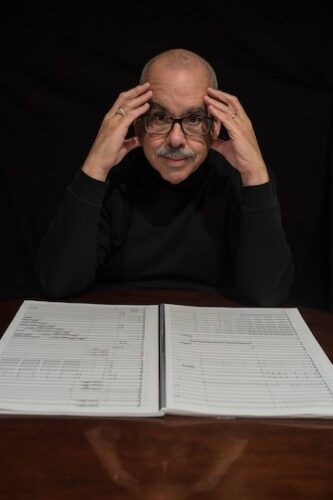

Composer Roberto Sierra, whose Concerto for Saxophones received its second performances at Symphony Hall November 13 – 15. Photo: Facebook

There were plenty of opportunities for individual players to shine. A ballet suite by Ukrainian-Puerto Rican composer Jack Délano supplied spotlight moments for wind and brass soloists. The strings had the stage to themselves and performed beautifully in the Rapsodía urbana by Alfonso Fuentes and the remarkably atmospheric On the Ethereal Nature of Luminescence by Luis Quintana. There were surprisingly realistic bird-call and tree-frog (coquí) effects at the beginning of Ernesto Cordero’s Mariandá. The percussionists showed fire and precision throughout, especially in movements from Roberto Sierra’s sixth and seventh sinfonías. And (I confess I don’t remember where) there was an especially gorgeous moment for an oboist, probably the Orquesta’s principal, Ivonne Maria Pérez Gorritz.

In the first half, composer Angelica Negrón, who is growing in her stateside reputation, was on hand to hear her Morivivi, and she was invited to come to the stage by Valdés to receive appreciative applause.

In the second, cuatro star Luis Sanz was a show unto himself, not only playing the descarga movement from Ernesto Cordero’s Concierto Criollo para cuatro y orquesta sinfonia beautifully, but providing a solo encore, a medley of familiar themes that had many members of the audience humming along. He also displayed some spectacular showmanship as he performed on his instrument, a small guitar with 10 steel strings, over his head à la Jimi Hendrix.

Conductor Valdés, who has been leading the OSPR since 2008 (longer than Nelsons has been leading the BSO, by the way), knows his Orquesta well, shows them off to great effect, and provided helpful introductions to each work. His colleague Irizarry was carismático y elegante when he took the podium, perfectly in keeping with the role Pops conductors are expected to play, but going well beyond that role, warmly encouraging the audience to sing and clap along with the music.

The camaradería onstage demonstrated how much these players and their leaders seem to like each other, and how moved they all were to be playing in Symphony Hall. There were huge smiles on stage and in the audience as someone from the right balcony unfurled a large Puerto Rican flag, and the Orquesta responded in kind by unfurling their own at the conclusion of the second half, followed by an encore, a beautiful medley of boleros.

But this concert was just one of four multicultural programs offered from Thursday November 13 to Saturday November 15. The BSO itself honored two Latin composers – Havana-born Tania León and Vega Baja (Puerto Rico)-born Roberto Sierra – with generous performances of their works in three subscription concerts led by Finnish conductor Dima Slobodeniouk, who was so memorable directing Mozart’s Requiem last May. After seeing both Friday night’s and Saturday night’s shows, it seemed to me that, for once, Johannes Brahms, whose second symphony closed each of the BSO programs, seemed somewhat of an outsider.

Tania León’s Time to Time, co-commissioned by the BSO and the Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, had its world premiere in these concerts, and León was on hand for pre-concert introductions to her work at each performance. I have read takes on the Thursday performance of Time to Time from A. Z. Madonna in The Boston Globe and Julie Ingelfinger from The Boston Musical Intelligencer; after hearing the work myself on Saturday night, I’m struck by the variety of ways in which León’s tone-poem can be perceived. She spoke about her inspirations – Japanese Noh drama and a famous haiku by Matsuo Bashō that contemplates the passage of time through a landscape metaphor:

From time to time

The clouds give rest

To the moon’s beholders

The piece is a striking collage of sounds in which the full orchestra, with a huge percussion array, still spoke like a chamber ensemble, with bursts of solo and ensemble music framing a tonal center that came and went like moonlight occasionally obscured by the shifting of clouds. Nothing about it said “Havana”; if any geographical place could be said to be evoked by the music, it may have been a garden near a Noh performance hall in Kyoto. This very demanding score, which León charmingly referred to as “my baby” in her remarks, was handled with tender loving care from Slobodeniouk.

I previewed the BSO’s first performance of Roberto Sierra’s Concerto for Saxophones in a 2019 profile of James Carter for the Fuse. At that point, I knew the work only from its recording (Caribbean Rhapsody, EmArcy, 2011, with the Sinfonia Varsovia conducted by Giancarlo Guerrero), but now I’ve had the pleasure of hearing it live twice. In some ways, the performances in the past few days were a personal triumph for Carter, and he relished the opportunity to return to Symphony Hall.

The 2019 Boston premiere was a one-off, conducted with great passion by Thomas Wilkins, who clearly believed in the work. The response to that performance led BSO management to program it again for Tanglewood in the following summer. But the pandemic shut down the BSO’s summer season, and it has been nearly six long years of waiting for Carter to have that richly-deserved second Beantown outing. This time, the BSO did it right, programming the work in three subscription concerts, allowing the artist full opportunity to have his spectacular gifts on display repeatedly in Symphony Hall.

Maximiliano Valdés conducting the Orquesta Sinfónico de Puerto Rico at Symphony Hall on Friday November 14. Photo: Hilary Scott, courtesy of the Boston Symphony Orchestra

I also know a bit more about the inception of the concerto than I did in 2019. I was fortunate to have a conversation on Thursday afternoon with Carter’s indefatigable manager, Cynthia Herbst of American International Artists. She told me with justifiable pride that she had brought the composer and the saxophone virtuoso together and had shepherded the Detroit Symphony’s commission of the work. She saw this as both a simpatico opportunity for Sierra to create for saxophone and a chance for Carter to reach deeply into the classical realm. Her vision was more than realized in the resulting piece, which has been hailed by reviewers everywhere it has been performed, praised as a brilliant showcase for Carter’s virtuosity and an enthralling musical experience. It never fails to bring audiences to their feet – although I have to note that a proportion of the Saturday night crowd stayed in their seats in silent unappreciation.

James Carter showed off every aspect of his prodigious technique in that performance – fluidity on tenor and soprano, percussive and slap-tongue effects, circular breathing, stratospheric high notes and growling low ones, and even sighs through his tenor at one point, evoking chuckles from the crowd. His execution of the written material was impeccable and his improvs ebullient. He capped it all with a solo encore of his own “JC on the Set,” the title tune from his first recording as a leader (JC on the Set, DIW, 1993).

What can I add to what has already been said about the Sierra concerto itself? Now that I have a better sense of where Sierra’s writing leaves off and where Carter’s improvisations begin, I am even more impressed with the symbiosis of this partnership. When they began as a form in classical music, concertos were often vehicles for their composers to show off their own instrumental virtuosity, so any improvisations they may have added to the written scores were organic. As time passed and concertos became vehicles for composers and star performers to collaborate, improvisation has been eschewed, or in some more modern cases, it has been approached gingerly by the composer, for fear that too much ad-libbing would blunt his or her intentions.

But Sierra’s concerto was written specifically for Carter, and he owns it now. It has become a unified artistic conception that could not achieve its purposes without both musicians giving their complete intelligence to it. What Sierra has written opens doors for Carter, and he strides through them with swagger. What he then plays is canny and cognizant of the written music before and after; his improvised thoughts are probably by now well-planned, but he still executes them with dazzling spontaneous additions from his enormous tool kit of effects, and he leads the music back into the written score with the same kind of grace he shows when he cues his small groups to return to the head of a jazz composition. I think there are very few concertos in the history of the form where the composer and interpreter are so deeply interlocked, and so magnificently successful.

James Carter at Symphony Hall, playing Roberto Sierra’s Concerto for Saxophones on Thursday November 13, with Dima Slobodeniouk conducting. Photo: Michael J. Lutch, courtesy of the Boston Symphony Orchestra

With all that said, the work is almost all flash and fire, and Slobodeniouk gave it plenty of both; however, its slow movement gives Carter only the briefest opportunity to show his soulful side. In its wake, I feel keenly that Carter would wow audiences again with a very different kind of classical piece, a pastorale or nocturne, something that would let him be as richly melodic as he is, say, in his recording of Billy Strayhorn’s “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing.” Sierra has done his part; I imagine that Thomas Oboe Lee might be just the person to give Carter the yin to this concerto’s yang.

All three BSO performances ended with Brahms’s second symphony. Readers may cluck, but I was so transported by the Sierra-Carter collaboration that I did not relish a return to business as usual, and I left at intermission.

Upon reflection, I wondered why there were so many empty seats on Saturday (as A. Z. Madonna wondered similarly in the Globe about the Thursday house). Did the programmers’ plan to balance the unfamiliar with the familiar backfire? Did BSO regulars stay away because of León and Sierra, and those interested in more adventurous music stay away at the prospect of a 45-minute meditation by Brahms? Maybe moving the Mussorgsky – Ravel Pictures at an Exhibition, scheduled for this coming weekend, to November 13 – 15 would have provided a payoff to the first half with familiar color and heart-on-the-sleeve drama. The Brahms could then have been moved to the upcoming series, balancing Joshua Bell’s performance of Thomas de Hartmann’s Violin Concerto.

At the November 14 concert featuring the Orquesta Sinfónico de Puerto Rico, composer Angelica Negrón bows. Photo: Hilary Scott, courtesy of the Boston Symphony Orchestra

But I can also point to the enthusiastic attendance at the October 23 – 25 concerts that juxtaposed Leonard Bernstein’s Three Dance Episodes from “On the Town” and Prokofiev’s brash second piano concerto with Aaron Copland’s rarely-performed Third Symphony, built around the famous Fanfare for the Common Man. That concert held me in my seat from first note to last, and not just because of the Fanfare. Yes, all three composers are well-known names, but any of these infrequently-performed works would have provided effective balance to the León and Sierra pieces.

On the other hand, the BSO could have provided exposure to American composers this season overlooks. Walter Piston’s Symphony No. 6, Howard Hanson’s Symphony No. 2, “Romantic,” or William Schuman’s Symphony for Strings are all pretty easy on the ear – any of them would have balanced this week’s program well.

There are other options for this “E Pluribus Unum” season that the BSO might have considered, and not just for the past three concerts – although programming them in any of the subscription concerts would also probably risk half-full halls.

Samuel Barber’s Knoxville: Summer of 1915 is a modern classic, but it would require booking a superior soprano like Kathleen Battle, Dawn Upshaw or Barbara Hendricks, and the BSO is already giving Barber his spotlight with a concert performance of his opera Vanessa, January 8 – 10.

More adventurously, I would dearly love to hear the BSO include the work of some senior living American composers in programs with an E Pluribus Unum orientation. Tobias Picker’s Keys to the City is a piano concerto of significance. Another example: John Adams’s Century Rolls is a big piece with a lot of fire, but, like Picker’s work, it would require booking a major piano soloist, and Emmanuel Ax owns this piece the way Carter owns Sierra’s concerto.

But these are only my fond wishes. I give hearty thanks this week for an impressive musical reality. The BSO deserves full credit for a major commitment to Latin composers, and for giving the area’s Puerto Rican community an historic occasion to celebrate.

More:

Thanks to Julie Ingelfinger of The Boston Musical Intelligencer, who, in her timely November 15 review of the Thursday concert, provided some important details that saved me a bit of research. Her review is well worth your attention. She noted that León’s Time to Time was commissioned with financial support from Catherine and Paul Buttenwieser and the New Works Fund of the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

Thanks to Julie Ingelfinger of The Boston Musical Intelligencer, who, in her timely November 15 review of the Thursday concert, provided some important details that saved me a bit of research. Her review is well worth your attention. She noted that León’s Time to Time was commissioned with financial support from Catherine and Paul Buttenwieser and the New Works Fund of the Massachusetts Cultural Council.

A. Z. Madonna’s review of the Thursday concert in the Globe is also worth reading, and the two reviews together provide interesting and different takes on León’s Time to Time.

The Boston Symphony Orchestra played Tania León’s Stride in January 2024, soon after the work won the Pulitzer Prize.

The London Philharmonic has posted a YouTube video with the composer discussing her work and excerpts of her Pasajes and Stride.

The City University of New York has posted an extensive YouTube video featuring an interview with the composer conducted by Terrance McKnight, and three of her works: “Oh Yemanja” (from Scourge of Hyacinths), Mistica (played by pianist Ursula Oppens) and a string quartet entitled Esencia.

As noted above, James Carter has recorded Roberto Sierra’s Concerto for Saxophones with the Sinfonia Varsovia conducted by Giancarlo Guerrero (Caribbean Rhapsody, EmArcy, 2011). The release also includes improvised solo interludes by Carter on soprano and tenor, and the title piece, a work for string quintet and saxophone that also features James Carter’s cousin, violinist Regina Carter.

The BSO has a long relationship with Sierra, beginning with the premiere of his Fandangos in 2012, when it was conducted by Domingo Hindoyan. The orchestra provided a video of that performance to YouTube.

The BSO also presented the American premiere of Sierra’s Sinfonía No. 6 in 2024, and posted a video of that performance to YouTube.

Both of those works were subsequently recorded by the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, led by Domingo Hindoyan (Onyx, 2023).

Those intrigued by the brilliant final movement of Sierra’s seventh sinfonia, which closed the first half of the OSPR’s Friday concert, are encouraged to hear the full recording of it, which has been posted to YouTube by a thoughtful contributor who also provides a page-by-page view of the score as the music plays. Hear and view it here. This contributor also has posted a recording with score of the sixth sinfonia. Hear and view it here.

Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube Music and other streaming services offer many other works by León and Sierra, including her Pasajes and his Sinfonía No. 3, “La Salsa,” which draws on forms used popularly in a lot of salsa recordings and performances.

Spotify, Apple Music, YouTube Music and other streaming services offer many other works by León and Sierra, including her Pasajes and his Sinfonía No. 3, “La Salsa,” which draws on forms used popularly in a lot of salsa recordings and performances.

James Carter’s performance of Billy Strayhorn’s “A Flower Is a Lovesome Thing” is found on his album Gardenias for Lady Day (Sony, 2003), a recording in honor of Billie Holiday that showcases Carter’s depth and sensitivity. Other notable works from this release are Victor Herbert’s “Indian Summer” and a chilling version of Abel Meeropol’s “Strange Fruit.”

One aspect of Carter’s work that Sierra’s concerto spotlights is his mastery of the blues (the dynamic last movement of the concerto is built on a common blues structure). I have created a playlist that shows Carter’s varied approaches to the blues, in compositions basic and complex, as a leader and as part of ensembles. You may hear the playlist if you are a Spotify subscriber by clicking here.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: Angelica Negrón, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Dima Slobodeniouk, James Carter, Luis Sanz, Maximiliano Valdés

Hard to imagine a more thoughtful, insightful, and comprehensive article. What a bounty of pertinent information and offered opportunities for further delving! Deep thanks, Steve Elman!