Jazz Album Reviews: Sounding Freedom — Two Journeys Through the Avant-Garde and History

By Brooks Geiken

Two jazz albums whose uncompromising visions succeed.

Three improvisers with wide-ranging musical affiliations have banded together to form Trio of Bloom (Pyroclastic Records). Drummer Marcus Gilmore, known for his work with pianists Chick Corea and Brad Mehldau; guitarist Nels Cline, a stalwart member of the band Wilco; and pianist Craig Taborn, who has been in bands led by James Carter and Bill Frisell, unite to form what is a decidedly avant garde trio. If free jazz is your thing, Trio of Bloom creates a generous helping of the kind of music that challenges and rewards attentive listening.

Three improvisers with wide-ranging musical affiliations have banded together to form Trio of Bloom (Pyroclastic Records). Drummer Marcus Gilmore, known for his work with pianists Chick Corea and Brad Mehldau; guitarist Nels Cline, a stalwart member of the band Wilco; and pianist Craig Taborn, who has been in bands led by James Carter and Bill Frisell, unite to form what is a decidedly avant garde trio. If free jazz is your thing, Trio of Bloom creates a generous helping of the kind of music that challenges and rewards attentive listening.

I don’t favor much contemporary electronic music, but Trio of Bloom succeeds by using its electric instruments (guitar and piano) in unusual and provocative ways. Opening with the Ronald Shannon Jackson song “Nightwhistlers,” the band gets down immediately. Gilmore’s furious beat starts the tune, followed with eclectic punctuation courtesy of Cline and Taborn. Gilmore drives the next track, the funky “Queen King,” during which Cline romps with the bass while Taborn plays a circus-like organ. The most experimental track on the album is the unpredictable “Bloomers.” The instruments flicker in and out, compelled by an inventive exploitation of repetition. Another noteworthy piece, the frenetic “Why Canada,” finds Gilmore and Taborn pushing and pulling each other in a sort of musical jousting. The shortest track on the album, “Gone Bust,” reveals a popularist side of the trio not previously explored. The Cline-penned tune embraces a rock groove that ends abruptly, leaving the listener wanting more.

In fact, every track evokes a different mood; there’s the pastoral beauty of “Breath,” the atmospheric “Diana,” the ethereal “Unreal Light,” and the multilayered sonic journey,“Forge.” Along with that variety, there’s an adept use of absence. For example, Gilmore drops out with intuitive regularity. Cline’s guitar work self-consciously stimulates the others, while Taborn has an uncanny ability to know what notes to sink into the mixture — and when to do it. Overall, Gilmore’s drumming is breathtaking, Taborn’s piano work is lovely, and Cline’s guitar playing is off the charts.

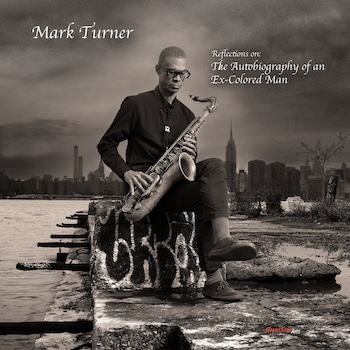

Mark Turner, perhaps the most highly regarded tenor saxophonist of his generation, has composed a musical opus titled Reflections on: The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man. (James Weldon Johnson, the author of Autobiography, was, along with his composer brother J. Roseamond Johnson, the creator of the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice And Sing”). Over the course of 10 tracks, Turner (tenor sax and narration), Jason Palmer (trumpet), Matt Brewer (acoustic and electric bass), David Virelles (piano, synthesizers), and Nasheet Waits (drums) collectively pay moving tribute to Weldon Johnson’s 1912 book.

“Movement 1. Anonymous” begins with a bass and drum introduction, followed by Turner’s recitation of a selection of Johnson’s book. The melodies played by Turner and Palmer recall some of the passages on classic Blue Note records. On “Movement 2. Juxtaposition,” Turner takes a section from the book that looks at the differences between how Southern whites and Northern whites related to Blacks. Virelles takes the music in an interesting direction, soloing in a personal way. “Movement 3. Pulmonary Edema” begins with a lovely Turner solo that shows why he is revered by musicians such as Ravi Coltrane and Miguel Zenón. Virelles provides minimal backing for an impressive demonstration of Turner’s fluid mastery of the tenor sax. Providing a contrast in mood, Virelles supplies a long introduction on synthesizer at the opening of “Movement 4. New York,” and then the full band comes in swinging. Brewer takes up the electric bass, which give the music some added punch.

One of the more predominantly spoken word pieces that resonate with our current political climate is “Movement 6. The Texan.” Here Turner recites a conversation about the value of multiculturalism between a racist Texan and an informed Northern man. A solo by Palmer underlines the poignantly relevant discussion. In a second section, the band, complete with synth, slowly muses on Johnson’s insights.

This is a powerful album on a number of levels. Johnson’s words deal with vital racial issues, and the music accompanies the commentary with a nuanced expressive aptness, underlining rather than highlighting. Turner selected some of the most provocative parts in the book — there is nothing compromising in his vision — and his sober, at times somber, compositions delicately illuminate the complexities of race relations.

The musicians apply their considerable gifts to this important contemporary opus, especially Virelles, who makes fierce statements throughout. Brewer and Waits support the musical drama in subtle ways as well. I had not previously been familiar with Palmer’s playing; I was impressed by his gentle dexterity with the horn. Kudos to Turner and company for an excellent album that, in its own modulated way, asks for activism.

Brooks Geiken is a retired Spanish teacher with a lifelong interest in music, specifically Afro-Cuban, Brazilian, and Black American music. His wife thinks he should write a book titled The White Dude’s Guide to Afro-Cuban and Jazz Music. Brooks lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.