Jazz Album Review: Pepper Adams Quintet — The Baritone Voice of Hard Bop Excellence

By Michael Ullman

Baritone saxophonist Pepper Adams was clearly a generous soul, as well as a stunningly accomplished jazz musician.

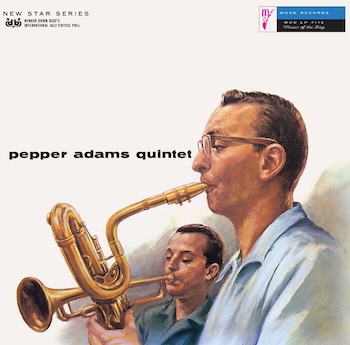

Pepper Adams Quintet (Mode Records, 45 rpm LP)

I first heard baritone saxophonist Park” Pepper” Adams in all his grit and glory on Charles Mingus’s 1959 masterpiece Blues and Roots. He introduces Mingus’s gospel-tinged “Moanin” with a repeated three-note phrase that lands with a resounding thud on the lowest note. This was somehow a powerful statement — the rock on which the piece rested. Adams’s ensuing lengthy solo was equally as engrossing. In that group, he was a counterweight to Mingus’s bass: his sound was huge, and his improvising so agile, it was as if he hadn’t heard how cumbersome the baritone saxophone was supposed to be.

I first heard baritone saxophonist Park” Pepper” Adams in all his grit and glory on Charles Mingus’s 1959 masterpiece Blues and Roots. He introduces Mingus’s gospel-tinged “Moanin” with a repeated three-note phrase that lands with a resounding thud on the lowest note. This was somehow a powerful statement — the rock on which the piece rested. Adams’s ensuing lengthy solo was equally as engrossing. In that group, he was a counterweight to Mingus’s bass: his sound was huge, and his improvising so agile, it was as if he hadn’t heard how cumbersome the baritone saxophone was supposed to be.

In 1959, Adams wasn’t absolutely new to recording. As we learn in the extensive, authoritative biographical notes to the newly issued 1957 45 rpm LP Pepper Adams Quintet, Adams, with his friend Thad Jones, had made a demo session as early as 1954. It didn’t go anywhere. Gary Carner’s notes tell us that the baritone saxophonist’s playing wasn’t immediately accepted. The problem was his sound. As astute a businessman as Alfred Lion, head of Blue Note records, thought Adams not only shouldn’t but couldn’t be making the sounds he heard: they had to come from a Black player. Lion is quoted as describing Adams’s playing as coming from “a Black baritone who is a rhythm and blues player trying to play jazz.” Lion must have been thinking of the then current models for contemporary baritones: the smooth-sounding Gerry Mulligan and perhaps Serge Chaloff. Adams’s sound hearkened back to the approach of Duke Ellington’s Harry Carney. He embraced the baritone’s aggressive heartiness.

Luckily for him, Adams was widely appreciated by a lot of musicians. He was a popular sideman. In April 1956, Adams was on a Paul Chambers Blue Note record in a bopping band that also featured John Coltrane. In April of that year, Adams joined a troupe of his Detroit homies (including Tommy Flanagan) for the Savoy session that became Kenny Clarke Meets the Detroit Jazzmen. Adams spent much of that and the following year with Stan Kenton. He also recorded with trumpeter Shorty Rogers’s big band. He was invaluable in these contexts: his sound solidified any reed section and he was a dexterous soloist. Jazz aficionados have their various favorite Adams recordings as a sideman: maybe his work with Donald Byrd (Off to the Races) and The Lyrical Trumpet of Chet Baker would be among them. He pops up in surprising places, such as the Benny Goodman big band of 1958 and later taking part in Joe Zawinul’s Money in the Pocket. Later on, Adams maintained a steady gig: for 11 years, beginning in 1966, he was with the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis big band, where many of us heard him repeatedly. And, of course, he made his own records, including hard bop masterpieces such as 10 t0 4 at the 5 Spot with Donald Byrd and Elvin Jones.

The five numbers on Pepper Adams Quintet were recorded in L.A. on July 10, 1957, with West Coast musicians: Stu Williamson on trumpet, Carl Perkins, piano, Leroy Vinnegar, bass, and Mel Lewis on drums. The 38-page booklet that accompanies the elegantly reissued Mode LP includes several pages of production notes. They chronicle producer Philipe Berman’s excitement at discovering one of the master tapes in stereo. He also explains the decision to reproduce the music on 45 rpm. The resulting sound is closer to the original, he tells us. Because of this, and perhaps a variety of other reasons, the sound on the Mode LP is splendid. I heartily recommend this album. As I listen at this moment, I marvel at the bright immediacy of Williamson’s trumpet. That said, the stereo separation seems to me a little extreme: as I listen, Carl Perkins is soloing on the right and the admirable bassist Leroy Vinnegar is way to his left. In 1957, producers were still excited about stereo reproduction.

Pepper Adams performing with the Thad Jones-Mel Lewis Orchestra during the 1970s. Photo: Michael Ullman

The session opens with pianist Perkins playing a bouncy introduction to the ballad that was a hit for Nat King Cole, “Unforgettable,” written by Irving Gordon. Perkins is a tactful part of a remarkable rhythm section: the pianist was understandably a favorite of West Coast musicians, including Dexter Gordon. In 1956, he made Introducing Carl Perkins; only three years later he died of an overdose. Famous for his version of walking bass, Vinnegar led his own recordings, including the popular Leroy Walks! Drummer Mel Lewis was, in those years, a constant presence in L.A. studios. He would become co-leader, with Thad Jones, of one of the most justly celebrated big bands of the modern era. On “Unforgettable,” Adams plays the melody in unison with Williamson: they match, even when it comes to the swells that end some of the key phrases. Then Adams takes over, infusing the tune with his huge, rumbling tone. He manipulates the melody respectfully, eventually abandoning it for a generally quick-paced solo that is notable for the subtleties of his phrasing. He’s a master of the changes.

The other standards in the program, which also features two originals, are “Baubles, Bangles and Beads” and “My One and Only Love.” The latter is played slowly and softly. Adams pushes out a note, withdraws, rushes here and then pauses there, squeezes out a high note, almost honks on a low note. He enthusiastically embraces his instrument’s gruffness, but is also capable of turning it tender. Despite its subtle dynamics, his solo seems gently inevitable. His manners are not mannerisms. The original “Freddie Froo” is a dashing uptempo bop piece. Here Williamson takes the first solo. The album ends with “Muezzin,” which seems like another feature for the trumpeter. Adams was clearly a generous soul, as well as a stunningly accomplished jazz musician.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 30 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. He is emeritus at Tufts University where he taught mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department.

Tagged: Carl Perkins, Leroy Vinnegar, Mel Lewis, Pepper Adams Quintet, Pepper-Adams

Such a beautiful piece of jazz writing. Check out that lede! And Michael follows through for the entire piece, making me want to track down every example of Peppers’ artistry he cites here. A piece like this makes me regret that Bill Marx’s arts criticism class at BU no longer exists. . . . Well, I regret that loss for a lot of reasons, not least because a valued colleague lost a paycheck. But here is what I see as a textbook example about how to write about music: Vivid descriptions that bring the music to life on the page, and deeply informed historical context. Read it, kids: this is how it’s done.