Jazz Album Reviews: Hazards Ahead –When Jazz and Poetry Intersect

By Allen Michie

Ideally, if the verse and the music work seamlessly together, they can create a third kind of art that is neither fish nor fowl. It can stand alone on its own merits.

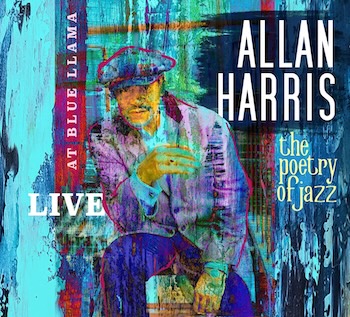

The Poetry of Jazz: Live at Blue Llama – Allan Harris (Blue Llama)

Revisions – Fred Moten and Brandon Lopez (TAO Forms)

Jazz and poetry are like those people whose friends set them up at a party because they seem like they should like each other. On paper, at least, they have so much in common—rhythm, improvisation, sophistication, and a kind of counter-culture cool. Both the jazz musicians and the poets are supposed to wear berets, smoke hand-rolled cigarettes, and be able to talk to one another about Jean-Paul Sartre at little round tables in basement clubs.

Jazz and poetry are like those people whose friends set them up at a party because they seem like they should like each other. On paper, at least, they have so much in common—rhythm, improvisation, sophistication, and a kind of counter-culture cool. Both the jazz musicians and the poets are supposed to wear berets, smoke hand-rolled cigarettes, and be able to talk to one another about Jean-Paul Sartre at little round tables in basement clubs.

In practice, however, it rarely seems to work out this way. The improvisatory element masks layers of discipline, hard practice, and detailed craftsmanship that go fathoms deep. If the jazz musicians and poets meet these days, it’s more likely to be in the faculty lounge at a university or a grant award ceremony than in an atmospheric jazz club. Beat poetry, to the extent that it ever really existed as much of a coherent force at all, has been dead for 75 years. Both jazz and poetry now move in so many different and often contradictory directions that the odds of sparks flying on a blind date are way less than 50/50.

Still, jazz is a genre that welcomes interdisciplinary connections with verbal art forms, drawing on its partial roots in the history of musical theatre. Poetry is about all of life, which includes (among other things) the culture and the aesthetics of jazz. Whereas novels are less performative, poetry has the flexibility, subjectivity, and imaginative restlessness to embrace encounters with other art forms. When the two intersect, the question becomes not so much if it works, but who decides if it works.

Two recent projects from Allan Harris and the duet of poet Fred Moten and bassist Brandon Lopez provide two starkly different approaches to both the words and the music. Together, they bookend two ways of looking at the nature of collaboration.

Allan Harris is a vocalist, guitarist, storyteller, and all-around old-school Harlem jazz musician. He has a soulful baritone voice that’s a bit like Grady Tate’s (a compliment). The Poetry of Jazz is his second live recording from Ann Arbor’s Blue Llama club, released on their house record label. You know that anyone who spent time as a kid at his aunt’s soul food restaurant across from the Apollo where musicians would stop by after concerts is going to have that undefinable it, and Harris does.

His approach to poetry and jazz is unusual and surprisingly traditional. He steers his five-piece band through a mix of jazz standards and originals, but he begins all but the first song with a reading from a classic poet. He pairs a poem with a song, like pairing a wine selection with the dinner entrée. The concept is unpretentiously not explained on the cover or the booklet. The classic poems are just presented, take them or leave them.

Shakespeare’s Sonnet 18 (“Shall I Compare Thee to a Summer’s Day”), for example, introduces Lionel Hampton and Johnny Mercer’s “Midnight Sun.” The poem is read straight, with no gawdawful attempt to rap with it or distort the iambic rhythms. Maybe it’s been a while since you really listened to Mercer’s lyrics—by putting them next to Shakespeare’s, Harris persuasively highlights Mercer’s poetic imagery. Is it too much to claim that Mercer is our Shakespeare of song lyrics?

Your lips were like a red and ruby chalice warmer than the summer night

The clouds were like an alabaster palace rising to a snowy height

Each star its own aurora borealis, suddenly you held me tight

I could see the midnight sun.

“Weary Blues” takes a different approach. Harris begins with a brief introduction to the early Harlem Renaissance, describing how Langston Hughes returned from Paris and checked out the jazz clubs in Harlem. Then Harris elaborates with a soulful electric guitar solo, setting up the groove and the atmosphere, before reciting Hughes’ poem of the same name. There’s another guitar solo halfway through the poem, just after the words the piano player in the poem is singing, as if to put them into the guitar’s voice. Harris is clearly speaking from memory, as a few words are substituted or conversationally added (no harm done at all). The words of the pianist are more sung than spoken, in contrast to the main narrative of the poem. There are subtle musical responses throughout by violinist Alan Grubner on top of the bluesy jazz chords from the rhythm section. This is peak jazz and poetry commingling: the lines are blurred between literary verse, song lyrics, and musical solos. The past is recontextualized in the present, and the present is grounded in a historical continuum.

Another highlight, and a favorite with the live crowd, is Maya Angelou’s “Still I Rise,” imaginatively paired with Nina Simone’s “Sea Line Woman.” The music goes into a bluesy funk, as well it should be after that empowering poem. The lyrics by George Houston Bass are about a prostitute, or at least a femme fatale who seduces men for their money, so I’m not sure that’s the best choice here for Angelou’s poem of fiercely proud self-worth. But Simone is a perfect example of the sassy, haughty, sexy kind of woman Angelou’s poem describes.

Allan Harris, a vocalist, guitarist, storyteller, and all-around old-school Harlem jazz musician. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Harris takes a wide, if canonical, view of poetry. Dylan Thomas’ “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night” is paired with Harris’ original “Shallow Man.” It’s not an angry or defiant song, but it’s also about cutting through the crap at the end of life. While the violin and electric guitar lock down a snaky blues/soul groove, Harris sings “All my plans turned out to be schemes and illusions. . . The truth is what I need, reality is just a dream.”

A favorite of mine is George Gordon, Lord Byron’s “She Walks in Beauty” paired with “With You I’m Born Again.” You’ll remember the song as a schmaltzy 1979 ballad by Billy Preston and Syreeta Wright but, in this context, the poetry primes us to hear the nighttime melody’s grace and seductiveness. “So soft, so calm, yet eloquent,” writes Byron. “Come bring me your softness/Comfort me through all this madness,” goes the song. It’s all done without melodrama or cheese. It turns out this is a tune with some lovely changes that should be covered by jazz musicians more often.

Two other Shakespeare sonnets are less successful. Sonnet 29 (“When in Disgrace with Fortune and Men’s Eyes”) is paired with “Charade” by Henry Mancini and Johnny Mercer. The poem is recited soulfully and directly — Harris isn’t playing a character. Mercer’s lyrics about a couple hiding their true selves don’t have any particular connection with Shakespeare’s sonnet. It’s fun, though, to hear Jay White lay down a strong jazz/rock foundation with some hip fillers on bass guitar. Sonnet 116 (“Let Me Not to the Marriage of True Minds”) is paired with Antonio Carlos Jobim’s “Desafinado,” which is, interestingly, not done as a bossa nova. Jobim’s lyrics admit all kinds of impediments about his lover, but at least the music gets the celebratory tone of Shakespeare’s classic wedding ceremony sonnet.

The album ends with “The Road Not Taken” by Robert Frost, paired with Harris’ original “Time Just Slips Away,” about hearing the life story of an old man who understands that “We are all the same, time just slips away.” It’s a fitting conclusion for an inventive album that finds rewarding artistic resonances across genres and across the generations.

I have less to say about Fred Moten and Brandon Lopez’s Revision. I don’t want to put myself forward as someone qualified to review it. All I can give you are some personal reactions. It’s either way over my head, or it’s . . . I don’t know.

Moten is a respected cultural theorist and scholar of Black Studies in addition to being a widely published poet. He’s a Professor of Performance Studies at New York University, and I’m not, so I’ll defer to his expertise on the merits of verse such as this from his poem “‘harriot + harriot + sound +” which he reads on the first track of Revision:

The pitch and time of luters

bring atlantic situations

all the way across. the moon

thing is a water thing at

midnight and the table

burst with variation.

the beautiful riot say

I’m not like this and

walk away embrace and

dig up under normandie.

Sometimes I get little or no sense of a beginning, middle, or end, and perhaps that’s the point. They just begin somewhere and end somewhere else.

You could say that the listener should just flow along with the sounds, but the sound of the words doesn’t strike me as particularly melodic. He’s creating collages with images and fragments of ideas, not making word music with primary attention to vowel sounds and scansion. As such, the relationship to the assertive music from Lopez’s solo acoustic bass is more conceptual than it is cohesive.

You could say that the listener should just flow along with the sounds, but the sound of the words doesn’t strike me as particularly melodic. He’s creating collages with images and fragments of ideas, not making word music with primary attention to vowel sounds and scansion. As such, the relationship to the assertive music from Lopez’s solo acoustic bass is more conceptual than it is cohesive.

Moten’s poetry may lack lyricism, but it’s not short on rhythm. “#5” is the most ambitious rhythmically. It falls apart and falls together contrapuntally with Lopez, who treats his bass like a drum as much as a stringed instrument, accented by Moten’s occasional percussive vocalizations.

Lopez is a marvel. In “#4,” he bows in such a scratchy way that the bass sounds like Jimi Hendrix’s distorted guitar. He’s a master of overtones that occasionally sound like electronics. He often plays riffs and arpeggios—more Philip Glass than Ron Carter—and at other times he’s completely free or subtly implying a pulse. In “#10,” his straight 8th notes at the start sound positively radical.

As provocative as both Moten and Lopez are individually, I’m not hearing strong structural connections between the words and the music. It’s more like the words and the music provide a context, perhaps an atmosphere, for the other to explore. There’s not the immediate responsiveness like you might expect with an improvising bassist shadowing a poet reading from a script.

So, as I asked in the introduction, who gets to decide if jazz and poetry are working together? Perhaps we’re conditioned by having singers in front of supporting bands to assume the poet holds the roadmap, using the “rules” or expectations of poetic communication to guide the musicians in either the overall feel of the performance and/or in the moment-to-moment responses. Or perhaps the poet is the guest in the ensemble: it’s the poet’s responsibility to fit in with the “rules” or expectations of the musicians and find a solid road that isn’t quite a song lyric and isn’t quite a detached recitation. (Rap and Slam Poetry artists have found more success and popularity with this, when they can resist overpowering whatever lyricism might remain in the music.)

Ideally, if the verse and the music work seamlessly together, they can create a third kind of art that is neither fish nor fowl, and it’s able to stand alone on its own merits. Sometimes this happens—it does at times on both of these records—but to my ear, the emphasis more often alternates between the two. “Let me not to the marriage of true minds admit impediments,” Shakespeare wrote; in jazz and poetry, impediments are often what make the marriage both difficult and fascinating.

Allen Michie has a PhD in English Literature, and he works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas.

Tagged: "Revision", "The Poetry of Jazz: Live at Blue Llama", Brandon Lopez, Fred Moten