Jazz Album Review: Aruán Ortiz’s “Créole Renaissance” — A Unique Sound

By Michael Ullman

Aruán Ortiz’s energy, his skill at creating surprises and variations, and his impressive keyboard mastery make his solo album fascinating.

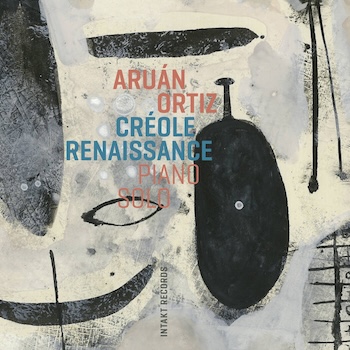

Aruán Ortiz, Créole Renaissance (Intakt Records)

Now living in Brooklyn, the Cuban-born pianist Aruán Ortiz has a philosophic bent and an impressive list of accomplishments. He is featured on some of the most celebrated, adventurous recordings of the last two decades, including Nicole Mitchell’s Maroon Cloud, Don Byron’s Random Dances and (A)Tonalities, Esperanza Spalding’s Junjo, and Steve Turre’s Woody’s Delight. He has composed for string ensemble and recorded repeatedly as a soloist, with trios, and with mid-sized groups.

Now living in Brooklyn, the Cuban-born pianist Aruán Ortiz has a philosophic bent and an impressive list of accomplishments. He is featured on some of the most celebrated, adventurous recordings of the last two decades, including Nicole Mitchell’s Maroon Cloud, Don Byron’s Random Dances and (A)Tonalities, Esperanza Spalding’s Junjo, and Steve Turre’s Woody’s Delight. He has composed for string ensemble and recorded repeatedly as a soloist, with trios, and with mid-sized groups.

His new solo disc, Créole Renaissance, refers to the French Négritude movement of the ’30s: three of his titles, beginning with “L’Etudiant noir” are named after short-lived, but historically important, journals of the movement. On “From the Distance of my Freedom,” the fourth number of Créole Renaissance, Ortiz speaks as well as plays. He doesn’t deliver an argument. Instead, without comment or context, he presents material for listeners to contemplate. “My history speaks through my existentialism,” he asserts, as well as “from my ancestral mysticism.” He repeatedly utters the phrase, “Black Renaissance.” Presumably, Ortiz is that renaissance. He plays from his Afro-Cuban experience, and with “no masks allowed.” “Primitivism versus modernism” is one of the dualities he mentions, but he then adds, “Surrealism.” These labels are simply placed in front of us — could they be overlapping alternatives? Meanwhile, between this series of nouns, the pianist supplies seemingly casual phrases on the piano that are often dissonant and unresolved.

Interestingly, although there are allusions to Afro-Cuban music, Ortiz is very free with rhythms: he never precisely swings nor does he show an interest in extended, continuous pulses. Following the verbal part of “From the Distance of my Freedom,” he solos restlessly, dashing all over the keyboard. He is fearless about when to pause or change tempo. His improvisations here and elsewhere include darting lines in the right hand, and heavy-handed sustained chords. Ortiz ends “From the Distance” with dissonant chords that clash like cymbals: they introduce a final sustained bass note.

The recorded sound of this Intakt disc emphasizes that stereo effect. We can clearly hear the way Ortiz’s left hand works. On “Première Miniature (Créole Renaissance)” his moods shift. Ortiz sounds cheerful as he scurries squirrel-like about the keyboard. On the other hand, “The Great Camouflage” is bleak. It moves like a dirge, a low note in the bass repeatedly answered by chords in the mid-range, with longish pauses as if we were meant to anticipate, not hear, the answering chords. I am not sure what the origin of “The Haberdasher” is, but it’s another playful piece, with staccato notes irregularly accented and widely spaced in pitch. Again, we don’t hear a continuous pulse, yet the music remains engrossing. “Seven Aprils in Paris (and a Sophisticated Lady)” begins soberly, with single notes intoned out of tempo. The occasional chord is sustained through the pedal. It’s a dark-sounding piece, not what this listener expected from “April in Paris” (though it tends to rain in that city all that month).

“Légitime Défense” feels like a series of lightning strikes. The track opens with clusters of notes up high. Then we hear sprays of staccato single notes and nervous answering chords played at a quick tempo. About two minutes in there is a pause, as if the piece had to regroup. This is free music, mostly free of obvious melodies, tempo, and consistent harmonies. That sounds like a lot of negatives, but Ortiz’s energy, his skill at creating surprises and variations, and his impressive keyboard mastery make his solo album fascinating. He makes it move in what I hear as comprehensible ways. It’s playful, not at all pompous. This pianist’s sound is unique, and well worth a listen.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.