Jazz Album Review: Bill Evans and Tony Bennett, 50 Years After

By Steve Provizer

Perhaps the most well-known jazz piano-vocal duo recordings were made in 1975 by Bill Evans and Tony Bennett. For me, these performances are sui generis — a high-water mark of the form.

Piano-vocal duos are a staple in the world of cabaret, but, as a rule, vocalists in jazz are backed by trios or larger ensembles. The musical tradeoff for doing without a rhythm section is clear: pianissimo is available, but fortissimo is tougher. No trading 4’s and 8’s with the drummer, no horn players to vary solos, and the pair may not be able to achieve the kind of pulse that some say qualifies as “swinging.”

Piano-vocal duos are a staple in the world of cabaret, but, as a rule, vocalists in jazz are backed by trios or larger ensembles. The musical tradeoff for doing without a rhythm section is clear: pianissimo is available, but fortissimo is tougher. No trading 4’s and 8’s with the drummer, no horn players to vary solos, and the pair may not be able to achieve the kind of pulse that some say qualifies as “swinging.”

But there are aesthetic satisfactions to be found in duets that can compensate for not being able to team up with a rhythm section. Most notably, the possibility of reaching a freer give and take, a kind of rhythmic and melodic judo that, in the best cases, can become a dance — one with surprising variations.

Perhaps the most well-known jazz piano-vocal duo recordings are those made 50 years ago, in 1975, by Bill Evans and Tony Bennett. For me, these performances are sui generis — a high-water mark of the form.

It was hardly inevitable that these two musicians would collaborate. They had met and publicly stated their mutual admiration, but they were traveling in different musical worlds. Evans was one of the most influential pianists in jazz during the second half of the 20th century and performed at straight-ahead jazz clubs. Before joining with Bennett, he had not worked in a duet with a singer. On Bennett’s part, as I note in this article, he was at a low point in his career. Attempts to make him sound more “contemporary” had flopped.

This match came about as the result of a suggestion to Bennett by singer Annie Ross (of Lambert, Hendricks and Ross). The musicians brought the idea to their respective managers (who were friends) and a deal with Fantasy Records was quickly done. Evans and Bennett met to decide on a repertoire and the pianist then spent considerable time working out arrangements.

Given their technical capacities, there was potential for a powerful musical symbiosis. Bennett’s vocal range was expansive, from high baritone to high tenor. He used vibrato for expressive ends, rather than habitually. His sense of dynamics was well-honed and his breath control was Tommy Dorsey-esque.

Evans moved fluidly and deftly through all ranges of the piano. He had a profound knowledge of harmony and selectively used dissonance to deepen the colors of the harmony and add interest to his melodic improvisational lines. All of these skills served to inspire a generation of pianists.

This said, the “personalities” of the music of Evans and Bennett differed in significant ways, which was reflected in their contrasting stage presences. Bennett had always straddled the jazz-pop world and knew how to “sell” a song. His big hits were pop tunes like “Because of You,” “Rags to Riches,” “I Left My Heart in San Francisco,” etc. Evans, on the other hand, was an introverted presence at the piano, uncompromising in his repertoire. His keyboard touch was subtle rather than percussive.

Given that disparity, there needed to be a matching of sensibilities. Each man had to do some emotional stretching. I’d characterize it this way: Evans had to look outward a bit more than usual and Bennett inward.

The pieces fell into place. The people in front of and behind the microphones established an atmosphere of mutual comfort and respect. The musicians made a commitment to careful listening. Each took the lead or followed as demanded by the music. Above all, the tunes chosen provided perfect vehicles for bridging any emotional gaps between Evans and Bennett.

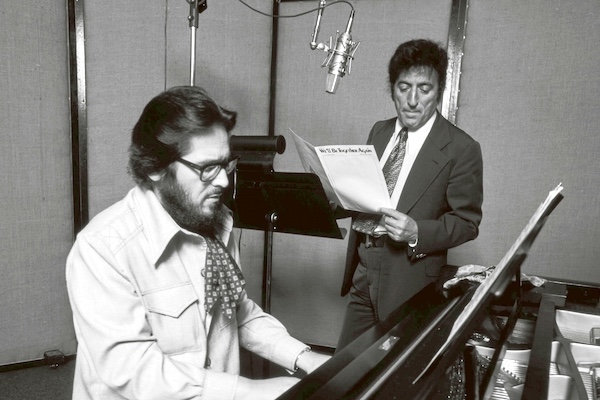

Bill Evans and Tony Bennett recording The Tony Bennet/Bill Evans Album. Photo: courtesy of the Princeton Public Library

The repertoire is superb, dominated by ballads or medium-slow tunes. Many of the tunes had been played by Evans for years — “Young and Foolish,” “Some Other Time,” “The Touch of Your Lips,” and “But Beautiful.” ”Waltz for Debby” is perhaps the most well-known Evans composition and, unusually, we hear the pianist solo in waltz time, instead of changing to 4/4 time.

The Evans intros and codas are small gems. And his accompaniment is much more than faultless. There are times I would have preferred that Bennett lay back a bit and not be quite so stentorian — for example, in “The Touch of Your Lips.” Evans can pull a full sound out of the piano, but nothing that can stylistically match Bennett in full bel canto mode. I must also note that the two don’t really reach an emotional agreement on “When in Rome.” Still, in almost every case, Bennett understands the texts and subtexts of the lyrics — his readings are spot on. After he made this album, he knew he had “come home” and went back to a repertoire that was almost exclusively from the Great American Songbook.

The aesthetic complementarity of these artists may not have been evident on the surface, but Evans and Bennett made the commitment to swim in deeper currents, with stunning results.

There are other stellar examples of the duet form. Among them: Mildred Bailey with Teddy Wilson in the ’40s, Lee Wiley and Ellis Larkins in 1954, Ella Fitzgerald with Oscar Peterson, Ellis Larkins, Paul Smith and Tommy Flanagan in the ’50s, Ran Blake and Jeanne Lee in the ’60s and Roberta Gambarini and Hank Jones in the early 2000s. These recordings and the Evans-Bennett collaborations are available online. I suggest you take a listen. You won’t feel that anything is “missing,” and your spirits will be refreshed.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Catherine Russell with Sean Mason.