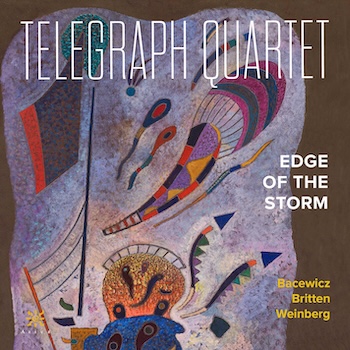

Classical Album Review: At the “Edge of the Storm” with The Telegraph Quartet

By Gary Lemco

An impressive series of performances that are not for the faint-of-heart.

In this album, the Telegraph Quartet — Erin Chin and Joseph Malle, violins; Pei-Ling Lin, viola; Jeremiah Shaw, cello — explores quartet music from the period of 1941 through 1951 by three composers who responded to a turbulent decade of political exile, mass genocide, and post-war rehabilitation. In the words of annotator Kai Christiansen, “Each composer featured on the album lived a unique wartime life that unmistakably influenced their equally unique masterworks of the period.”

The String Quartet No. 4 of Grazyna Baceicz (1909-1969) celebrates the career and personality of Poland’s pre-eminent female composer of the 20th century. Bacewicz and her family survived the Nazi occupation of her country, fleeing the Warsaw uprising. This music projects a feeling of having risen from the ashes and searching for hope. A dark, lugubrious opening figure in the Andante quickly gathers significant energy; the Allegro moderato returns to somber musings. The harmonies become shrill and aggressive, even vibrant with hopeful militance. The viola part is expressive, but soon cedes its optimism to a haunted figure played over pizzicato strings. The second theme, lyrical, is marked “sweet” and “melancholy.” The colloquy once more assumes a feverish intensity, underscored by passing dissonances and active counterpoint. Another extended moment of haunted lyricism emerges, just prior to a mad rush of a coda.

The second movement, Andante, also opens with unearthly harmonies, its syntax close to that of Bartók’s. Weaving chromatic harmonies coalesce into melodic fragments that generate striking duets from the cello and the viola, including brief bits of polyphony. The music settles into a kind of phantasm, dreamy but disturbed, ending quietly. The last movement, Allegro giocoso, takes the form of a rondo, a Polish oberek in neoclassical form, similar to a work by Haydn, though touched by modern irony. There’s a touch of humor when the players intone a rural hornpipe figure. Hints of political oppression notwithstanding, the music cavorts and sails with a renewed sense of spiritual direction — the coda is symphonic in scope.

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) composed his String Quartet No. 1 in D Major in 1941, for a commission from Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge. Britten was living in exile in America. He had left England just prior to the outbreak of WWII because he and tenor Peter Pears had declared themselves to be pacifists. Though intended for the British ensemble Griller Quartet, the premiere of Quartet No. 1 was given by the Coolidge Quartet on September 21, 1941 at Occidental College. The work has a curious structure: the first and third movements are brief, the second and fourth movements are more than twice their length.

Movement one begins Tempo primo, Andante sostenuto and emits a sound almost outside human experience. The upper string vibrates while the cello comments down below via pizzicato and arpeggios. The Tempo secondo, Allegro vivo, suddenly propels us forward, the first violin almost dizzy with bristling, syncopated accents. The two impulses alternate and trade fragments, reaching for a heaving synthesis dominated by the cello’s somber plaints. The tessitura is extended into exceedingly high — virtually cosmic — registers as it lingers above the cello pizzicatos. The entire complex eventually evaporates. The compressed second movement, Allegro con slancio, thrusts us into a scherzo-march interrupted by disturbing triplet figures. This is music of acerbic wit and iron resolve that has much in common with similar episodes in Beethoven and Shostakovich.

The third movement, Andante calmo, conceived in 5/4, has been characterized as “a requiem for a lost world.” Stratospheric violins compete with the lower range of the viola and cello. The music anticipates the darkly meditative sonorities of Britten’s 1945 opera Peter Grimes, which is based on the poem by George Crabbe. At moments, the sonority of the quartet becomes organ-like; there are anguished cries from individual instruments. The music, when it slows down, seems to stagger into delirium, groping for harmonic resting places. The organ texture returns; the cello is put into pizzicato motion while the upper strings sing the coda as part of an extended lament.

The last movement displays Britten’s mastery of intricate and robust counterpoint. During the Molto vivace the cello takes a solo position against his fellow strings. This pesante tune returns — two octaves above its original position — as the drama becomes symphonic and sonically daring as it sails into a final cadence.

The tumultuous life of Polish-born Mieczyslaw Weinberg (1919-1996) finds ample documentation in his music, a potent assembly of diverse works that were conceived by “a powerful spirit enclosed in a frail body,” as one admirer described the composer. Having fled Poland to the Soviet Union, Weinberg found few consolations after 1948, when Soviet propaganda and biased antisemitism reigned as official, cultural policies. Despite consistent support from Shostakovich, Weinberg was arrested and remained a prisoner until Stalin’s death in 1953. The 1946 Quartet No. 6 had been proscribed by Soviet authorities. The work would not be published until 2006; it received its premiere performance in 2007 by Quatuor Danel, whose second violinist, Gilles Millet, coached the Telegraph Quartet on this work in 2019.

Quartet No. 6 in E Minor unabashedly refers to the trauma of war. Its first movement, Allegro semplice, is deliberately set in the unusual Locrian mode. Degrees of the scale are flattened; the use of diminished fifths and minor seconds establishes an unsettling, anxious mood. The agitated, melancholy theme that opens the first movement evolves in sonata form, often interrupted by sobbing or wistful gestures – especially from the viola. The theme is soon developed more aggressively, in the manner of Weinberg’s idols, Shostakovich and Miaskovsky. Both viola and first violin engage in mournful dialogue with the cello. A four-note motto or “fate” that arose earlier concludes the movement.

The second movement, Presto agitato – attacca, explodes into violent martial figures, whose dire defiance is almost vicious, rife with glissandos and swift, jabbing, relentless attacks. The music breaks off, Allegro con fuoco, suddenly tuning up for a feral square-dance. There’s also a solo violin, klezmer-ish invocation of lamentation. The fourth movement, Adagio takes its cue from J.S. Bach and Shostakovich. It is a sad fugue made up of individual voices who fade away, suggestive of the ghosts of Holocaust victims The morbid atmosphere intensifies with movement five, Moderato commodo, an eerie totentanz in the form of a theme and variations. Given an occasional nod at gallows-humor (by way of muted instruments), the music might be an agonized, cello-driven homage to a common musical idol for Weinberg and Shostakovich — Gustav Mahler.

The final movement, Andante maestoso, marks a culmination of sorts, embracing both majesty and tragedy. Again, the flattened modality of this music adds a peculiar, ethnic fever to the gestures, marked by violent pizzicatos and melodic tissue harmonized in thirds. A whirling violin dance, interrupted by dark cello exhortations, moves to the viola’s lament, easily reminiscent of a farewell vista in a Shostakovich symphony. Emotionally taut and expressive in extremis, the music becomes a fanfare for cosmic weltschmerz.

An impressive series of performances that are not for the faint-of-heart.

Gary Lemco studied with Carine Arena and Jean Casadesus. Having majored in literature and philosophy, Dr. Lemco endeavors an inter-disciplinary approach to musical and cultural projects. He is the author of Nietzsche as Educator and hosts “The Music Treasury” over KZSU-FM, Stanford University. This review is dedicated to the political writings of Professor Judith Lichtenberg.