Visual Arts Review: Isamu Noguchi at the Clark — Sculpture and Unfinished Projects

By David D’Arcy

This impressive show of more than 32 works concentrates on what Isamu Noguchi could do with stone, sometimes just leaving it in abstract forms, either raw or polished, often imagining it (and cutting it) into what were meant to be essential shapes.

Isamu Noguchi, Sculpture to Be Seen from Mars, 1947, photomural: unrealized model in sand. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 01646, Photo: David D’Arcy

In a new show at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, the work of one artist is framed inside that of another — the sculptures (and more) of Isamu Noguchi are in the glass-and-steel enclosure designed by the architect Tadao Ando.

Artists can be competitive. In this case, each makes the other’s work radiate.

For those who haven’t been to the Clark in the last 10 years, Ando’s building is a sleek, low-lying structure of stone, glass, and steel with galleries on ground level and a spacious exhibition space downstairs. It opens onto an expansive square pool, with hills rising in the background, a typically Berkshire scene, but one that might just as well be found in an Asian landscape painting — tiny figures trekking into distant places.

Noguchi (1904-1988), who was born in Los Angeles to a Japanese father and an American mother, moved through modernism to abstraction and back and forth; there were experimental detours, but there was an ever-present influence of Japan. To call Noguchi eclectic might seem to undervalue his work, but it’s accurate; he draws from a range of sources in what’s on view at the Clark, all on loan from New York’s Noguchi Museum in Queens, New York.

Isamu Noguchi: Landscapes of Time, a show of more than 32 works running through October 13, concentrates on what Noguchi could do with stone, sometimes just leaving it in abstract forms, either raw or polished, often imagining it (and cutting it) to make what were meant to be essential shapes.

That’s not all he did, or tried to do. Theater and performance were other media for him. In 1946, Noguchi worked with his longtime collaborator Martha Graham to reimagine the betrayal and revenge of Medea in a dance adapted from Euripides’s tragedy. He designed a platform in the form of a serpent for a dancer (Graham) playing Medea to stand on. Atop that was a “Spider Dress” of thin brass wires radiating outward; it stood on the serpent frame whether the performer was there or not. Electrifying is one obvious adjective for this construction. And it is minimal. Minimalism wasn’t a named art movement then, but the term suggests a zen influence, an emphasis on an economy of expression — mute but resonant. Here it stands as a shape that frames the character of a vengeful wife that also stands as a memorial (and a threat) when she is not standing inside it. The wire “dress” is barely there, which makes it hard to convey its power in words or in a photograph. All the more reason to go see it.

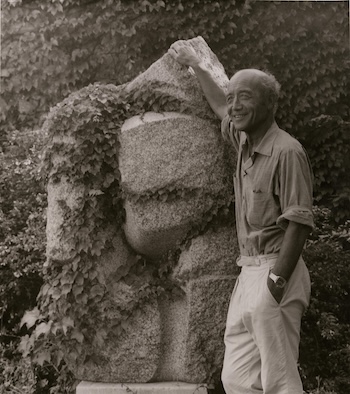

Isamu Noguchi with Indian Dancer (1965–66) in Long Island City, NY, 1981. Photo: David Finn. The Noguchi Museum Archives, 04378.

Speaking of spareness, a photograph is all that remains of what for me was the most memorable work in the show, a grandly conceived sculpture that was never built, a mute warning about our capacity for self-destruction. The model that Noguchi made and photographed has been lost.

The project is Sculpture To Be Seen from Mars, which was imagined on a grand scale to memorialize, in advance, a far grander event, the annihilation of the world that Noguchi expected to happen. The sculptor planned his memorial as a vast face sited in a desert, with a nose whose bridge measured a mile. It was meant to be viewable from as far away as from Mars — a safe observation point, Noguchi seems to be telling us.

Noguchi made a model in sand of cartoonish features, with a singular raised brow, two eyes, a peaked nose, and a mouth with an enigmatic expression — his Mona Lisa? The face suggests bemusement rather than shock; this is anything but the horror of Edvard Munch’s The Scream. It was only two years after America leveled Hiroshima and Nagasaki with atomic bombs, no doubt a grim event for the conflicted artist. Noguchi’s father was Japanese and mother American. He was both, and spent part of World War II, by choice, in a detention camp for Japanese-Americans on an Indian reservation in Arizona. Before and after the A-bomb, Japanese culture shaped his life and work.

As divided as Noguchi might have been by his own origins, his fatalism was rooted in an insistent sense of shared humanity. His skeptical view was that the atomic bomb would inevitably extinguish life on earth. Was the expression on that face the silent recognition that humanity lacked the sense to save itself?

Noguchi already had his sights set beyond the studio, not just in this project, which was never built, but in gardens, parks, and memorials. His 1951 design for a Hiroshima Memorial was denied by a Japanese government agency charged with commissioning that work. His biographer, Hayden Herrera, suggests it was probably because Noguchi wasn’t considered Japanese enough. The same bell-shaped Memorial to the Atomic Dead was put forward for Washington, DC, in 1982, but unrealized. (A model of Noguchi’s proposed Bell Tower for Hiroshima [1950], planned as a 70-foot structure with bells from around the world, is in the show.) An essay on the artist’s memorials, built and unbuilt, can be found on the Noguchi Museum’s website.

Noguchi’s Akari floating at the Clark. Photo: David D’Arcy

Power broker Robert Moses prevented the sculptor from designing a playground by the new United Nations in New York. Thomas Hoving, a New York parks commissioner who later led the Metropolitan Museum, killed a design for a children’s playground in Riverside Park. Rejection, a reality for any artist, dates back early in Noguchi’s working life, including his time assisting Gutzon Borglum, who led the team that built Mount Rushmore. Borglum told the young man he would never be a sculptor.

Yet, despite it all, Noguchi still fortunately found a way to be almost everywhere. His signature Akari light sculptures in paper, copied shamelessly and pirated in the market, are throughout the packed gallery, floating above the sculptures on view. It was as if the show were a festive event, and it is. For the round Akari, which means “light for illumination” in Japanese, Noguchi distilled a deceptively simple technique in which shapes of paper were folded, often around a light source.

Once again, there’s more here. Herrera, in her book Listening to Stone, quotes Noguchi praising the eloquent brevity of the Akari because “they appeal to the particular love of the Japanese for things ephemeral, like cherry blossoms, like life.” Given the spiraling cost of anything called art these days, the Akari are affordable and portable, and they don’t call for a wonky academic explanation or a Warholian shrug to be appreciated.

The brochure for Landscapes of Time, prepared by the Noguchi Museum, cites Noguchi on the traditional and the transitory:

The quality of poetic, ephemeral and tentative. Looking more fragile than they are, Akari seem to float, casting their light as in passing. They do not encumber our space as mass or as a possession. If they hardly exist in use, when not in use they fold away in an envelope. They perch light as a feather, some pinned to the wall, others clipped to a cord, and all may be moved.

And they give pleasure. What’s not to like?

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: "Isamu Noguchi: Landscapes of Time", Clark Art Institute

Noguchi’s work can be categorized as “serene.” Multifaceted, his work included sculpture, gardens, furniture, lighting, household objects, ceramics, and set designs.His mature work was at once subtle and bold, minimalist but often functional, traditional and yet modern.In everything he did, there was always attention to detail.

I have to correct you, David. Noguchi actually did create a piece in Japan signifying the horrors of Hiroshima. This is Noguchi’s stunning railing for architect Kenso Tange’s Hiroshima Memorial Peace Bridge that was completed in 1953. This is a true collaboration, based upon ancient Japanese cultural forms and modernism.

Needless to say, I am a great Noguchi fan and own several of his brilliant functional pieces.