Jazz Album Review: Trombonist/Composer Matteo Paggi’s “Giraffe” — Surprisingly Tall

By Michael Ullman

The planned variety of sounds and rhythms is the adroit work of a composer dedicated to both freedom and his own version of continuity.

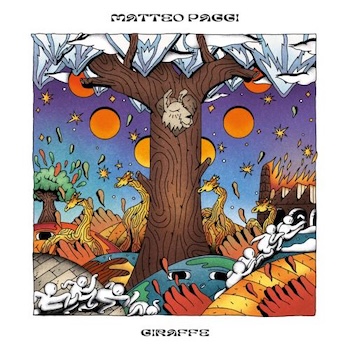

Matteo Paggi, Giraffe (Jam/Unjam)

Giraffe is a quintet led by the Italian trombonist Matteo Paggi whose (eccentric) explanation for the name has something to do with the distance between a giraffe’s head and heart. Paggi is a highly experienced musician; he first studied classical music before switching to jazz in time to earn a master’s degree in trombone from the Conservatorium of Amsterdam. In 2017 he arranged to study composition, chamber music, and conducting at Stanford and Marquette. In 2019, he moved to his current base of operations, Amsterdam, where, among his various projects, he founded the band Giraffe.

Giraffe is a quintet led by the Italian trombonist Matteo Paggi whose (eccentric) explanation for the name has something to do with the distance between a giraffe’s head and heart. Paggi is a highly experienced musician; he first studied classical music before switching to jazz in time to earn a master’s degree in trombone from the Conservatorium of Amsterdam. In 2017 he arranged to study composition, chamber music, and conducting at Stanford and Marquette. In 2019, he moved to his current base of operations, Amsterdam, where, among his various projects, he founded the band Giraffe.

Giraffe (the disc) was recorded after Paggi presented the band and the music in concert. He didn’t immediately record after the tour. For a while, he, in his own words, sat around “chilling and became fatter.” Then, in 2024, after he was sufficiently stoked, he brought his core band — Lorenzo Simoni, saxophone, Masako Sakai, pianist, Jonathan Ho, double bass, and drummer Andrea Carta — into the studio. The last three numbers on the album were recorded four years earlier, in the spring of 2020, and they feature trumpeter Andrea del Vescovo, pianist Yunah Han, bassist Mischa Voeykov, and drummer Said Vroon. The members of both bands are classically trained, and their playing is precise.

Giraffe is a varied set, though it is frequently mellow. Paggi plays the sweetly melancholy melody of his “Return” with beautifully controlled long tones, using minimal vibrato. He is accompanied by Han’s piano. “Return” is the trombonist’s feature, a showcase for his full-bodied sound, which gradually builds in tension as he rises to the higher ranges of the instrument. On the other hand, Paggi’s “Gero” begins boisterously. The horns play a repeated three-note figure by themselves and then the band comes in with — literally — a bang. Han picks up the figure, now playing over a backbeat from drummer Vroon, and the horns come in to play the first part of the boppish melody. After a minute, there’s a surprise. Everything seems to die out — except for Paggi’s solo trombone. He plays sagging long tones that seem on the verge of disappearing. Soon, accompanied by random tinkles on piano and the occasional rap by the drummer on his rims, Paggi leads us in unpredictable directions. Soon he rips upward on the trombone. Agitated, he emits short bursts and rude blats that are interspersed with his gorgeous long tones. Eventually, the piece turns into a group improvisation over the insistent backbeat we heard earlier. The planned variety of sounds and rhythms is the adroit work of a composer dedicated to both freedom and his own version of continuity.

“Ricordo” begins with a gentle riff on the piano, over which Paggi and saxophonist Simoni play unison long tones. The melody unfolds naturally, after the entrance of bassist Kiat and the cymbals of Carta. No one needs to keep a constant beat. The piece is then turned over to Kiat, who, like the others, feels no need to show off his virtuosity. For a while, someone (probably Paggi) hums in the background. Much of the bass solo is in the upper range: it’s delicate rather than powerful. The piece comes to a temporary stop after five minutes. (This kind of surprise is typical of Paggi’s compositions.) The trombonist plays a transitional couple of notes and, suddenly, the band launches into machine-gun staccato phrases. The drummer, on tom toms, keeps up this insistent attack, as the horns begin to sound increasingly aggressive.

“Things That Build Concepts” is almost as intriguing as its title. Again, Paggi writes a melody that’s played, pacifically, over rattling drums. After a couple of minutes, the rhythm drops out, except for occasional bass notes and individual beats on snares and hi-hat, as saxophonist Simoni solos, this time with a hint of boppishness. The disc opens with “Ham and Sun.” Sakai plays a delicate intro and then Paggi enters with his customary long tones. The piece is made to build gradually. I am not sure where the ham comes in. Giraffe ends with “Slow My Skiing,” whose first section is composed of quick staccato phrases by the horns over bass lines, and the drums playing a nearly constant figure on snare, varied with rolls accented by strikes on the crash cymbal. The second section features expansive long tones, and then there’s a return to the opening. Paggi’s solo is humorous. He begins with an expiring tone and continues with what sounds to me like muted anxiety, muffled tones that lead to a strange passage in which Paggi sticks to one pitch, before he finally escapes.

Giraffe is like that. It’s full of surprises. The multisectioned compositions are expertly played and fun to listen to: complicated, embracing shifts in tempo, sudden halts, and occasional raptures.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: "Giraffe", Andrea del Vescovo, Jonathan Ho, Lorenzo Simoni, Masako Sakai, Matteo Paggi