Book Review: “Émile Zola: A Determined Life” — Naturalist, Reformer, Visionary

By Thomas Filbin

What our planet needs now is the reincarnation of a writer who, while combing through the nooks and crannies of society for painful truths, uses depictions of the present to demand future changes.

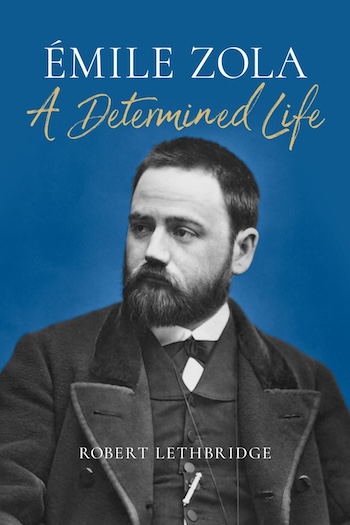

Émile Zola: A Determined Life by Robert Lethbridge. Reaktion Books, 304 pp., $38.

Émile Zola embodies the qualities of an engaged author, a first-rate writer who was unafraid of speaking truth to power. The impact of his work went beyond the page, propelling him into social activism. Already a superstar in the second half of 19th century France with numerous novels, essays, and reviews, Zola plunged into the Dreyfus case headfirst after he protested the abhorrent frame-up of a career army officer who happened to be a Jew. This biography by British academic Robert Lethbridge makes for enjoyable reading as it underlines the relevance of the life of a writer whose books explored, in massive imaginative detail, war and peace, wealth and poverty, truth and delusion.

Émile Zola embodies the qualities of an engaged author, a first-rate writer who was unafraid of speaking truth to power. The impact of his work went beyond the page, propelling him into social activism. Already a superstar in the second half of 19th century France with numerous novels, essays, and reviews, Zola plunged into the Dreyfus case headfirst after he protested the abhorrent frame-up of a career army officer who happened to be a Jew. This biography by British academic Robert Lethbridge makes for enjoyable reading as it underlines the relevance of the life of a writer whose books explored, in massive imaginative detail, war and peace, wealth and poverty, truth and delusion.

Born in Paris in 1840, Zola moved with his family to Aix-en-Provence, but he returned to Paris at 18 after his father’s death. He failed at school and was employed as a clerk, later working at the publishing house Hachette, where he discovered his vocation as a writer. He wrote reviews and essays on literary and social topics while fiction took a realist, naturalist direction that attempted to depict life across all the classes of France, from corporate drawing rooms to the fish markets. He first lived in an unheated room, later in a boarding house whose paper-thin walls gave him an earful of the world of students, prostitutes, and pimps. Exposure to the underside of the city — and its dehumanizing poverty — inspired him to assume the role of tribune to the underclass. His novels depict existence as it was survived (or not) beyond the grand boulevards. Butchers, house painters, and laundresses appear in his books because that was the world he observed with a poignant but clinical eye. Zola wrote: “Paris frames my window (and) was a source of consolation but also of my happiness.” Lethbridge notes that Zola often compared Paris to an ocean because of its vastness and variety.

The background of the Dreyfus affair can be traced to the horrid defeat the French military suffered in the 1871 Franco-Prussian war. The ineptitude of Napoleon’s nephew, Louis Napoleon, who was first elected president but then decided to crown himself as a monarch (please don’t say this cannot happen here and now) led a bumbling France into combat with the superior Prussian army. The military collapsed like a squashed work of origami at the battle of Sedan. The annexation of Alsace and Lorraine into the new unified Germany was an injury not healed until the next war. French hostility toward the Germans yearned for a scapegoat, a traitor who would excuse the deflation of the Second Empire. The Dreyfus affair was that public alibi. The shame and anger at the 1871 surrender ripened decades later, when Dreyfus was accused of leaking military secrets to the now unified Germany under Prussian leadership. A lowly major, Alfred Dreyfus, was sentenced to life on Devil’s Island until Zola and others dug up the dirt and went public.

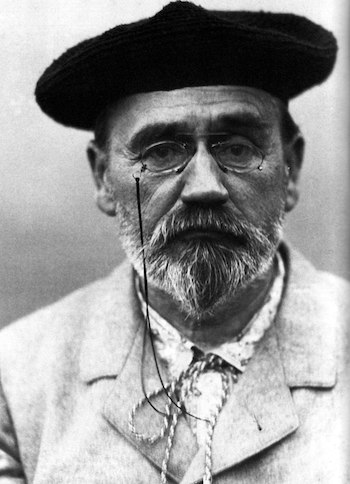

Émile Zola in 1902. Photo:Wiki Commons.

Zola is perhaps best known for his early, once-shocking novel, Thérèse Raquin, as well his incendiary attack on the government in J’Accuse. But there is a strong argument to be made that his master works are the twenty volumes of Les Rougon-Macquart, a series of intertwining novels published between 1871 and 1893 that chronicle two families and their descendants, actors whose trials and tribulations are symptomatic of the social environment of the period. Zola believed, strongly, that heredity was key to determining who we are and what we do. His was a kind of scientific sociology. We are who we are destined to be, but he left the door open for social change once people become conscious of that reality. The characters of the novels are both rich and poor, at the top of the social order and at the bottom of the heap, wrestling every day with their fate, often turning to alcohol and sex for pleasure or solace. Zola advocated for the common man, but he was under no illusions as to how the entrenched powers of social class and economic oppression dictated the course of their lives.

Lethbridge highlights the range of Zola’s intellectual and creative energies. Literature and political life were not enough; he was, for example, a self-invented art critic who championed Manet. Zola would hang out with painters like Bazille, Fantin-Latour, Degas, Monet, and Renoir, listening carefully as they proposed, and argued about, their theories of art. The late 19th century was a heady time given political turmoil and the emergence of Modernism. This book catches the exuberant spirit of the age: rebellion, reflection, re-invention.

Zola’s personal life was in some ways an acknowledgement of his literary vision –perfection is beyond human capacity. His marriage to Alexandrine was childless. After he hired Jeanne Rozerot, a seamstress, to live with them, he began an intimate relationship with her that produced two children. Zola’s solution was to maintain two residences — near one another — and keep two families happy. Zola died in September 1902 from apparent carbon monoxide poisoning; the chimney of his apartment had been stopped up. The writer’s wife and dog survived but, like all celebrity deaths, stories circulated that it was not accidental. There were claims it was suicide or murder arranged by anti-Dreyfusards who wanted revenge on an old enemy. It is both comforting and disturbing to see that conspiracy theories seem embedded in human consciousness.

Zola’s reputation has never seriously diminished—he remains a cornerstone of French literature. Lethbridge has written an engrossing narrative, but those who wish to go deeper should consult Frederick Brown’s 1995 biography of Zola, which is three times the length and offers much more detail. Still, Lethbridge grasps Zola’s purpose “…to reveal to his readers worlds that are kept out of sight by the powers-that-be (Parisian slums, the grim realities of rural life…, the hidden cogs behind political machinations,… base appetites behind respectable facades).” Zola’s definition of a work of art: “…a corner of creation viewed through a temperament” has stood the test of time. What our planet needs now is the reincarnation of a writer who, while combing through the nooks and crannies of society for painful truths, uses depictions of the present to demand future changes.

Note: Published in August 2020, Oxford University Press’s English translation of Doctor Pascal marked the first time that Émile Zola’s 20-book Les Rougon-Macquart series was available in print under one publisher. A 2021 Fuse interview with Zola scholar Brian Nelson explores what it means to have uncut versions of the French writer in English. There’s also a Fuse talk with Julie Rose, who translated Doctor Pascal for OUP. Want more? See a Fuse review of Zola’s The Conquest of Plassans.

Thomas Filbin’s reviews have appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Boston Globe, and The Hudson Review. He teaches writing at Suffolk University.