Jazz Album Review: “Izipho Zam (My Gifts)” — A Sign of Its Time

By Michael Ullman

Perhaps Izipho Zam (My Gifts) might have become as well known as Pharoah Sanders’s Karma — if Impulse! rather than the tiny cooperative label Strata-East had recorded it.

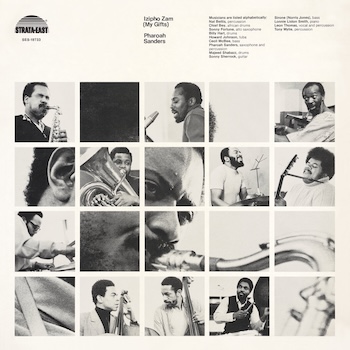

Pharoah Sanders, Izipho Zam (My Gifts), recorded on January 14, 1969. (Strata-East)

John Coltrane was never more influential than in the years after he died on July 17, 1967. His overblowing, his wild breathy swirlings in the upper range of his instrument, and the sheer intensity of his sometimes out-of-tempo free playing extended the range of the saxophone and, one is tempted to say, of its meaning. He also made the soprano saxophone popular again.

John Coltrane was never more influential than in the years after he died on July 17, 1967. His overblowing, his wild breathy swirlings in the upper range of his instrument, and the sheer intensity of his sometimes out-of-tempo free playing extended the range of the saxophone and, one is tempted to say, of its meaning. He also made the soprano saxophone popular again.

After his passing, the saxophonists in McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones bands, Alice Coltrane (and others) seemed to be trying to recreate the aura, if not the exact notes, of his playing. Coltrane, of course, didn’t introduce the idea of music as a spiritual force, but he showed how it might work in avant-garde jazz as both an uplifting experience and an antidote to the corrosive political climate of the Vietnam years. The saxophonist’s most popular recording remains A Love Supreme, which he made in one day, on December 9, 1964. It was nominated for a Grammy; it now seems surprising it didn’t win. More startling was the 38-minute improvisation called Ascension, recorded on June 28, 1965. There were three tenor saxophonists in Ascension’s band of eleven, and Pharoah Sanders was among them. The title was revelatory: to the post-bop avant-garde, their music was a kind of religious event. After Coltrane’s passing, which seemed shockingly early to those of us who were his fans, a church opened in San Francisco in his honor. (The Church of John Coltrane was also called the One Mind Temple.) Some visitors felt the transcendent vibe. It is said that the Kansas City saxophonist Norman Williams assumed the title “Bishop” after visiting the Church of John Coltrane.

Improvised music was also frequently viewed as a homage to Africa. One outgrowth of that was the multiplication of percussionists on recordings, as well as the numerous instruments they played. Sanders’s recordings from the late ’60s included Message from Home (home, it was implied, was Africa), and also Journey to the One, and Village of the Pharaohs. His most popular, and I daresay most influential, recording was Karma, which featured a nine-member band that included vocalist/yodeler Leon Thomas. Recorded on February 14, 1969, it begins with “The Creator Has a Master Plan”. This accessible work opens with Sanders playing long tones grandly. He then adds gritty overtones, fluttering trills, and ecstatic shrieks over a welter of percussion in a track that, nonetheless, seems pacific. As if to cement the Coltrane connection, the main body of the piece begins with a bass figure that mimics Coltrane’s melody in A Love Supreme. Thomas sings the lyric: “The creator has a master plan/ Peace and Happiness through all the land.” It was hummed by many a hip college student, who may have found, as I did, the music a release from, or perhaps a way to rise above, the pressures of the war, the draft, and the riots. [A much more direct expression of protest: Leon Thomas’s “Damn Nam (Ain’t Goin’ to Vietnam)”.]

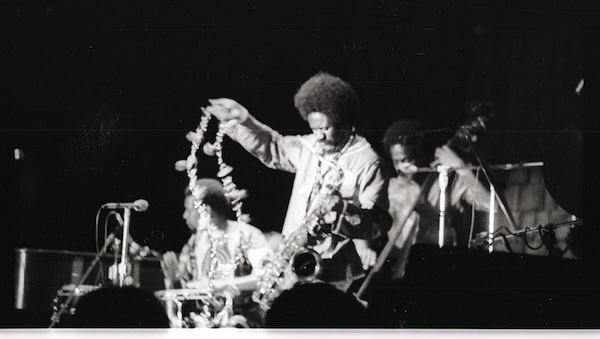

Pharaoh Sanders in Detroit in the early ’70s. Photo: Michael Ullman

Izipho Zam (My Gifts) was recorded on January 14, 1969, exactly a month before Karma, by a 13-piece band that included five or six (if you include vocalist Leon Thomas) percussionists. Here’s the rest of the band: Sonny Fortune on alto sax, Howard Johnson on tuba, Sonny Sharrock on guitar, Cecil McBee and Norris Jones on bass, and Lonnie Liston Smith on piano. It was a milestone recording in one way: Izipho Zam (My Gifts) was recorded by the tiny cooperative label Strata-East. Sanders’s next albums would be for the much more widely distributed Impulse! label, which Coltrane had made prestigious. Perhaps Izipho Zam (My Gifts) might have become as well known as Karma — if Impulse had recorded it.

The session opens with a similarly inspiring assertion phrased in a melody that is just as catchy and memorable: Thomas sings the lyric to “Prince of Peace” with fervor: “Prince of peace, Won’t you hear my plea, Ring your bells of peace, Let loving never cease.” The piece begins with the ringing of what sound like sleigh bells. The percussionists, including the piano, surround the singer, who soon is improvising with his innovative yodels. Later, tubist Johnson interjects a short solo, and then Lonnie Liston Smith plays brisk chords and rattling tremolos over the ever-shifting percussion. The twelve-minute “Balance” opens with the musicians creating a kind of out-of-tempo texture rather than emitting phrases — this is followed by a pause. Then, something surprising happens. After the near-passive introduction, Sanders introduces a good-time boppish melody. Soon, though, he slides into his wildly shrieking style in front of a wall of sound, amongst which Johnson’s tuba once again stands out. After a few minutes, Sanders restates the melody and they get going again. In about five minutes, the wall of sound builds into a sonic assault over which Sanders barely manages to wail. The title cut, “Izipho Zam”, is also the longest. It begins quietly, with Thomas improvising wordlessly and a bass playing a recurrent triplet figure while the horns play long tones. Then everyone seems to wait and see. What they are waiting for appears after four minutes: it’s a genial, islandish melody and rhythm. The melody, as restated by Sanders after 12 minutes, couldn’t be more welcoming. It’s good to have My Gifts back. It was a sign of its time.

For over 30 years, Michael Ullman has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. He has emeritus status at Tufts University, where for 45 years he taught in the English and Music Departments, specializing in modernist writers and nonfiction writing in English, and jazz and blues history in music. He studied classical clarinet. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. He plays piano badly.