Jazz Album Review: Pianist Paul Bley’s “Open, to love” — Waiting to Be Splashed With Sound

By Michael Ullman

What is most striking here is Paul Bley’s patience as a pianist, his practice of playing a chord or even a couple of notes and letting them hang in the air as if he were an outside observer, listening to their gradual fading.

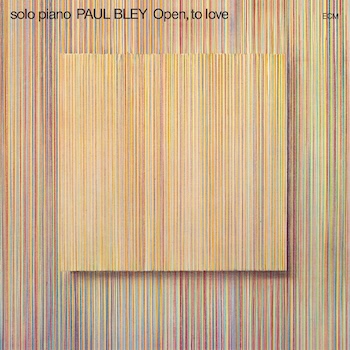

Paul Bley, Open, to love (Luminescence ECM LP)

Recorded on September 11, 1972, Open, to love was recorded on the same piano and in the same room in Oslo where a year earlier Chick Corea made his solo albums called Piano Improvisations, and where Keith Jarrett recorded his ECM debut, Facing You. It was a remarkable series of achievements for the pianists and for the young entrepreneur, ECM’s Manfred Eicher. All three recordings remain fresh, even startling. I have my original copy of Open, to love, which I bought right around when it was released. The piano sound on the original was somewhat brittle. This Luminescence LP sounds better in subtle ways; the piano seems marginally further away, with less harsh overtones.

Recorded on September 11, 1972, Open, to love was recorded on the same piano and in the same room in Oslo where a year earlier Chick Corea made his solo albums called Piano Improvisations, and where Keith Jarrett recorded his ECM debut, Facing You. It was a remarkable series of achievements for the pianists and for the young entrepreneur, ECM’s Manfred Eicher. All three recordings remain fresh, even startling. I have my original copy of Open, to love, which I bought right around when it was released. The piano sound on the original was somewhat brittle. This Luminescence LP sounds better in subtle ways; the piano seems marginally further away, with less harsh overtones.

The repertoire on the disc is mostly familiar, at least to Paul Bley’s more discerning fans. The tunes are mostly by his ex-partners Carla Bley and Annette Peacock. The exceptions are “Started,” Bley’s own radical reworking of “I Can’t Get Started,” and Roy Eldridge’s “I Remember Harlem.” In the latter, despite Bley’s reliance on the same half-note pattern that underlies Eldridge’s 1950 recording, and despite having previously recorded “I Remember Harlem” with its proper name at least three times, Bley renames the piece “Harlem” and claims it as his own composition. (I am guessing that ECM had demanded originals, and a famous 22-year-old recording by a swing trumpeter didn’t match their expectations.) Bley had recorded “Start, Closer” and Carla Bley’s “Ida Lupino” on his 1965 trio album (Closer, ESP, 1965).

What is most striking about these new versions is Bley’s patience as a pianist, his practice of playing a chord or even a couple of notes and letting them hang in the air as if he were an outside observer, listening to their gradual fading. He seems to be experimenting with the sound of this instrument. He begins, and I find this amusing, with “Closer,” attributed to Carla Bley. He plays an unexpected chord and waits, as if to watch the sound dissipate. The music is not in an identifiable tempo. It forces us to listen in a different way, as if we are waiting to be splashed with sound.

I once heard him talk about the challenge of playing the piano, each approach somewhat different. He’d avoid certain registers and notes, he told us, if the piano weren’t up to sounding them correctly. (He found the instrument I assigned him to when we brought him to Tufts University acceptable but not thrilling.) There’s no sign of dissatisfaction on Open, to love. He begins “Started” with a series of upward-moving rich chords, played firmly. Then he seems to sit back and plays more gently with a lot of pedal. At one point he plays quiet chords and plucks at the strings with his right hand until he surprises us with a sudden gentle closing chord. He then turns to what I heard him call his one hit record, Carla Bley’s unforgettable “Ida Lupino.” Its innocent melody suggests a child dancing, or maybe playfully emerging from a thicket. Bley’s improvisation is full of thrusts, outbursts, and retreats played over the whole range of the piano. “Harlem” is the other richly melodic piece, in a bluesy mode. There are no gaps in the left hand on this performance. It’s a delightful revisiting of a worthy piece. The record ends with Annette Peacock’s “Nothing Ever Was, Anyway.” Here, Bley goes for drama. “Nothing” begins with a sustained note and then moves to others via giant steps, played with a variety of touches, seemingly centered around its initial intervals. My conjecture is that “Nothing Ever Was, Anyway “refers to the 1970 recording, Nothing Is, by the spaceman Sun Ra. If so, it would be typical of the sophisticated wit and ingenuity of this solo set.

For over 30 years, Michael Ullman has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. He has emeritus status at Tufts University, where for 45 years he taught in the English and Music Departments, specializing in modernist writers and nonfiction writing in English, and jazz and blues history in music. He studied classical clarinet. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. He plays piano badly.