Classical Album Review: Sir Simon Rattle conducts the Music of Mahler and Weill

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Sir Simon Rattle and Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra solve the riddle of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 7. The conductor and the London Symphony Orchestra also offer a refreshingly impish, characterful traversal of music by Kurt Weill.

No Mahler symphony—not even the sprawling, unwieldy Eighth—has thrown interpreters and listeners for a loop quite so well as No. 7.

Premiered in Prague in 1908, the “Song of the Night,” as it’s sometimes subtitled (on account of its two “night music” movements), picks up, chronologically, from the shattered fragments left by the ending of the Symphony No. 6. Yet rarely have its opening bars evinced such a phoenix-like aspect as in Sir Simon Rattle’s new recording of the score, his third overall but first with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra (BRSO).

That’s fitting, given that Rattle’s account of the Sixth with these same forces (out last year) stands as one of the epic Mahler statements of the last decade. Their new performance of the Seventh features all the excellent qualities of that recording—warm, resonant ensemble; impeccably balanced textures; purposeful tempos—combined with a sure-footed grasp of Mahlerian style and character.

To hear that consistently across all five of the Seventh’s movements is rare. True, the first four, with their evocations of the natural world and its menacing shadows usually come off well. But the unrelentingly sunny finale, with its echoes of Wagner and village bands in the town square? That’s the ultimate Mahlerian puzzle.

Here, though, Rattle seems to have solved it, with an approach that connects this ebullient rondo to the rest of the Symphony as neatly as you’ll likely hear it done. A big part for the reason for his success lies in the total trust it shows in Mahler’s dynamics: the BRSO’s close attention these results in a performance that’s surprisingly lucid and singing. As a result, a Haydn-esque character prevails, often folksy and vigorous, even as scars from the previous movements (like the recurring, cascading chromatic scale figure) hint that not everything’s as it seems.

The symphony’s first four movements are likewise multidimensional expressive spaces, most spectacularly the central Scherzo. In this performance, the clarity of its various moving parts emphasize the section’s “story” of fragmentation, unity, and disintegration brilliantly; the tuneful, lyrical moments stand out strongly by contrast.

In the “night music” movements that frame the Scherzo, Rattle’s tempos are altogether well-judged. The earlier one is wonderfully crisp and light on its feet, though troubling undercurrents are never far removed and its allusions to other Mahler symphonies emerge readily. Meanwhile, the Andante amoroso sings with magnificent delicacy.

As for the big first movement, Rattle’s timing comes in a bit under his first recording of the Seventh from Birmingham in the ‘80s. Yet this one never feels hurried. The introduction’s shards unfold mysteriously before leading into a snapping, striding Allegro, whose counterpoint is beautifully balanced and quiet moments intensely focused.

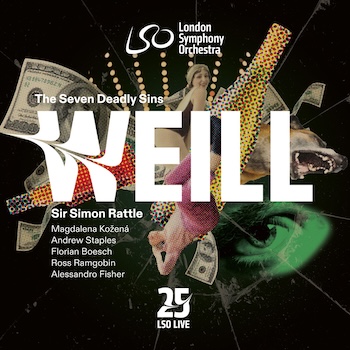

Rattle’s versatility as a conductor comes out on another disc he helms, this one devoted to theater music by Kurt Weill with the London Symphony Orchestra. The highlight of this effort is a set of rarities: “Vom Tod im Wald,” “Lonely House” (from Street Scene), and two of Weill’s Four Whitman Songs.

Rattle’s versatility as a conductor comes out on another disc he helms, this one devoted to theater music by Kurt Weill with the London Symphony Orchestra. The highlight of this effort is a set of rarities: “Vom Tod im Wald,” “Lonely House” (from Street Scene), and two of Weill’s Four Whitman Songs.

The first, hauntingly sung by bass-baritone Florian Boesch, is potently delivered, its wind- and brass accompaniment lending a wry acerbity to Weill’s setting of Bertolt Brecht’s grim poem about a murder in Mississippi. “Lonely House,” on the other hand, offers dreamy mystery, though tenor Andrew Staples’ voice sounds a bit distant from the larger ensemble.

He fares better in the adaptation of Whitman’s “Dirge for Two Veterans,” in which the tenor navigates Weill’s high-tessitura writing securely. Meantime, baritone Ross Ramgobin delivers “Beat! Beat! Drums!” with bristling confidence.

The remainder of the album is devoted to more familiar numbers.

There is no shortage of recordings of Weill’s last collaboration with Brecht, The Seven Deadly Sins, though this one sometimes feels a touch restrained and lacking in acid. Part of this is due to soprano Magdalena Kožena’s essentially warm and reflective take on the part. At its best, her tack lends a depth of humanity to the performance you don’t always find. At the same time, the “Wrath” and “Lust” movements benefit from a grittier approach.

That’s not an issue, however, in the LSO’s performance of Kleine Dreigroschenmusik. Here, everything speaks as it should: with swaggering panache (“Anstatt-dass Song”), cheek (“Die Ballade von angenehmenen Leben”), slinky character (“Tango-Ballade”), or just plain sweet lyricism (“Polly’s Lied”). Rattle and his band clearly know their stuff, and this is a refreshingly impish, characterful traversal of some really fine music.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: BR Klassik, Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, LSO Live, London-Symphony-Orchestra