Jazz Album Reviews: Guitar Players Rejoice — Cherished Joe Pass and Wes Montgomery Sessions Reissued as High-End LPs

By Michael Ullman

Wes Montgomery and Joe Pass are master jazz guitarists who sound nothing alike.

Wes Montgomery, The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery (Riverside, Craft LP)

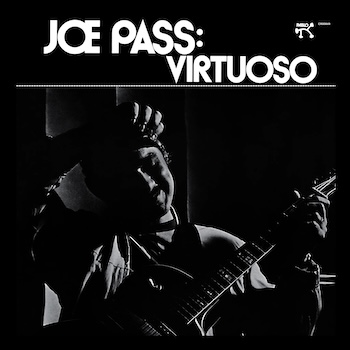

Joe Pass, Virtuoso (Pablo, Craft LP)

Here are two of the deservedly best known, even cherished, jazz guitar records reissued as high-end LPs, quiet as a mouse, by Craft Records. Recorded 14 years apart, the music on these albums remains luminous. Montgomery and Pass are master jazz guitarists who sound nothing alike. In 1960 Montgomery was in the middle of his most satisfying years as a leader. (Splurge and buy his collected Riverside recordings.) Joe Pass’s solo record Virtuoso wowed guitarists and jazz fans alike. It must have sold well; Pablo would subsequently issue three more solo albums by Pass, all entitled Virtuoso.

Here are two of the deservedly best known, even cherished, jazz guitar records reissued as high-end LPs, quiet as a mouse, by Craft Records. Recorded 14 years apart, the music on these albums remains luminous. Montgomery and Pass are master jazz guitarists who sound nothing alike. In 1960 Montgomery was in the middle of his most satisfying years as a leader. (Splurge and buy his collected Riverside recordings.) Joe Pass’s solo record Virtuoso wowed guitarists and jazz fans alike. It must have sold well; Pablo would subsequently issue three more solo albums by Pass, all entitled Virtuoso.

There was a time that The Incredible Jazz Guitar of Wes Montgomery was just about everyone’s favorite jazz guitar record, rivaled perhaps by his own Full House. It was recorded on two days in 1960, January 26 and January 28. At the time, Wes Montgomery was 36 and after a long stint with the Lionel Hampton band, had recorded repeatedly with his brothers for Pacific Jazz. He had made just one previous record for Riverside — a trio session with organist Mel Rhyne. He was, by jazz standards, a little old to be making his biggest splash. There were several things holding Montgomery back. Evidently, he was afraid of flying. Worse still, he lived in Indianapolis with his large family. In those days Indianapolis was a daunting distance from Manhattan. In his notes to Wes Montgomery: The Complete Riverside Sessions, producer Orrin Keepnews tells us, astonishingly, that Riverside was loath to spend the money to transport their soon-to-be star guitarist to New York City to make a single record. The solution was that, on the day before his own session, Wes would record with Nat Adderley on the cornetist’s Work Song.

The sessions went off with few hitches. Keepnews tells us that the one problem was that Montgomery didn’t necessarily approve of his own solos. His standards for his own playing must have been impossibly high. Today, it is easy to see what makes The Incredible Jazz Guitar stand out. It introduced Montgomery’s best known composition, “West Coast Blues,” as well his simply titled “Four on Six” and “D Natural Blues.” Also, a huge part of what made The Incredible Jazz Guitar so memorable was the presence of pianist Tommy Flanagan. (The quartet also included brothers Percy and Albert Heath.) In an interesting act of deference, Montgomery lets Flanagan take the first solo on “D Natural Blues.” Flanagan’s entrance is one of the great moments on the album, one that he seems to have prepared for. The guitarist’s intro and theme statement centers around short phrases. It sounds intriguing, if a little square. But then we experience the sudden release, the relaxation and swing, of Flanagan’s entrance and subsequent solo. It’s hard not to settle further into the couch when listening to that excursion. Montgomery shows off his quicksilver facility on the up-tempo “Airegin.” He inevitably swings, no matter how often he varies his techniques. The band anticipates exactly where he is going. On “D-Natural Blues” they move seamlessly into double time after Montgomery switches to octaves. It sounds spontaneous. On “Four on Six” the guitarist plays around the beat masterfully and displays a dazzling sequence of techniques, including the rapid octave playing for which he became famous. I am just as entranced by his ballads, particularly “Polka Dots and Moonbeams.” Montgomery’s later albums for Verve sold more, and some of them, such as the sessions with Wynton Kelly and Jimmy Smith, I wouldn’t want to be without. Listening to “Gone With the Wind” here, however, I wonder why his Riverside albums didn’t receive the same level of attention. The sound on this Craft recording is generally exemplary in its clarity. I heard something that I hadn’t previously noticed: the session with “Mr. Walker” sounds different, the guitar placed farther back in the sound stage and a little muffled. That we can hear such things is a tribute to Craft Records.

Wes Montgomery said he was first inspired by Charlie Christian. For Joe Pass, it was (astonishingly) Gene Autry, the singing cowboy. Born in 1929, Pass was well known as an impressively skilled sideman, recording frequently in the ’60s for Pacific, for instance, before his recordings as a leader made an impact. His life wasn’t easy. He talked readily of the addiction that kept him from accomplishing what he could in the music business during the ’50s. He spent years at Synanon: one of his early recordings is Sounds of Synanon. Then, sober and purposeful, he recorded over 200 sessions before his death in 1994. I heard him with Oscar Peterson and Ella Fitzgerald. With Peterson, he used his fast-finger picking to create lines that rivaled the pianist’s roulades. With Tatum-esque downward runs, breaking up the rhythm or blasting through the chord changes, he presented himself as the virtuoso that he was. One of Pass’s albums is named Chops: it is as if to say, take that, Bird — on it he plays Charlie Parker vehicles like “Relaxin’ at the Camarillo” and “Yardbird Suite.”

Wes Montgomery said he was first inspired by Charlie Christian. For Joe Pass, it was (astonishingly) Gene Autry, the singing cowboy. Born in 1929, Pass was well known as an impressively skilled sideman, recording frequently in the ’60s for Pacific, for instance, before his recordings as a leader made an impact. His life wasn’t easy. He talked readily of the addiction that kept him from accomplishing what he could in the music business during the ’50s. He spent years at Synanon: one of his early recordings is Sounds of Synanon. Then, sober and purposeful, he recorded over 200 sessions before his death in 1994. I heard him with Oscar Peterson and Ella Fitzgerald. With Peterson, he used his fast-finger picking to create lines that rivaled the pianist’s roulades. With Tatum-esque downward runs, breaking up the rhythm or blasting through the chord changes, he presented himself as the virtuoso that he was. One of Pass’s albums is named Chops: it is as if to say, take that, Bird — on it he plays Charlie Parker vehicles like “Relaxin’ at the Camarillo” and “Yardbird Suite.”

Once he signed with Norman Granz’s Pablo label, it was inevitable that Pass would make solo albums. Joe Pass: Virtuoso was the first, and it has never sounded better to my ears than on this Craft LP. I have the promo copy sent me by Pablo when the record came out. The Craft sounds (I am perhaps making up this word) tangy-er. There’s a little more high end and a slightly richer bass. The result is a more precise, more solid sound and feeling. The repertoire is standards and Parker’s “Blues for Alice.” It’s tempting to focus on Pass’s obvious facility, admiring his version of the bop anthem “Cherokee,” where, already playing at a fast tempo, he interrupts the melody to dash off some rapid fire lines, punctuated by the occasional chord to orient us. His ballads are less restless: they encourage us to appreciate his unsentimental way with familiar melodies, like “Stella by Starlight.” He states his introduction to “My Old Flame” with block chords, going on to play games with the rhythm in the bridge, allowing himself to pause as if to listen to the resonance of his own low notes. When he breaks into his typical fast single-note lines, it feels like a second kind of release. If I were to compare him to another solo ballad player, it would be to Art Tatum, another player willing to leave the swing rhythm behind as he wows us with cleanly articulated lines along with intriguing harmonic variations. Guitar players rejoice.

For over 30 years, Michael Ullman has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. He has emeritus status at Tufts University, where for 45 years he taught in the English and Music Departments, specializing in modernist writers and nonfiction writing in English, and jazz and blues history in music. He studied classical clarinet. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. He plays piano badly.

OK, I have to get these discs, listen,and then listen along with your notes. Wonderful work, Michael.