Jazz Album Reviews and Commentary: Jazz Composers’ Omnibus 2024, Take 2

By Steve Elman

In four (more) projects from 2024, jazz-oriented composers supply some of the decade’s best music so far.

… in times like these, to have you listen at all … – Adrienne Rich

In August, I looked at four releases from some respected names in jazz composition and found much worthwhile music, although not as much as I had hoped for. By contrast, four more composition-oriented releases came to my attention by the end of 2024 — by Frank Carlberg, Kevin Harris, Jamie Baum, and Florian Weber — and each one of them is a jewel. I have given each a good deal of listening (just as they deserved), and I had the additional pleasure of hearing some of Kevin Harris’s music played live, which enriched my understanding powerfully.

The listening was also a sobering experience in a way that had nothing to do with the music. Here are four artists of consummate ability making music that is rich and worthwhile. But in the sea of music we inhabit — a sea of music that is audible wallpaper everywhere we go, emotional drapery in our films and games, an engine for our on-stage spectacles or ecstatic dance experiences, and all the other utilitarian functions that vie with serious appreciation — I repeatedly wondered: How will listeners who could love this music find their way to it? How will they listen? Can the creators sustain themselves on the tiny segment of the public that will find their music and involve themselves in it?

I also wondered, Who are the people who are giving this music the hearing it deserves? At least two of the composers I spotlight here are cultivating their audiences directly. The other two give concerts, but I’m not sure how well they are received.

It was gratifying to see some of these astute listeners personally, when Kevin Harris played the Regattabar in Cambridge in December 2024 and performed much of the music on his new recording Embers. Harris (an associate professor at Berklee) has seized the challenge of self-marketing and built his audience from the ground up. The house at the Regattabar was full and the response to Harris’s art was enthusiastic.

Jamie Baum (who teaches at the Manhattan School of Music) is also an assiduous self-marketer, and I suspect that her audience, which is mostly NYC-based, turns out for performances by her “Septet +” with a commitment like that of Harris’s.

Frank Carlberg, a three-time MacDowell Fellow, augments his performances (again mostly in the NYC area) with academic connections — he teaches jazz performance and composition at the New England Conservatory, and directs the NEC Jazz Composers’ Workshop Ensemble.

Florian Weber is based in Germany; according to his handsome website, he has married an active performance career in both classical and jazz contexts with academic positions to create what appears to be a sustainable way of life.

But not one of these four is in any sense “popular.” Perhaps that does not matter to any of them. But it is a heartbreak to me that in a time when music can provide so much sustenance for the soul their work is appreciated by so few.

The four recordings here (along with Bruno Råberg’s Evolver, which I reviewed in my August feature), are among the best things I heard in 2024, and their impact will stay with me for quite a while.

This post will look at each one in turn, approximately in the order of the project’s relationship to “traditional” jazz performances.

Kevin Harris, pianist, composer, and leader of the Kevin Harris Project. Photo: Facebook

When I heard Kevin Harris’s quintet at the Regattabar on December 6 last year, I knew right away that his new CD Embers (independently released on Kevin Harris Project Records) needed to be part of this end-of-year survey.

For the most part, Harris works in the frame of a small group, but his ideas are big. Comparing his writing to that of Charles Mingus in the early ’60s and Herbie Hancock in the late ’60s is not faint praise. He stands on the shoulders of these masters, adds a singular personal voice, and has recruited strongly individualistic players to give his music definitive interpretation.

He is not content with simple theme-solos-theme structures, although the pieces on Embers roughly follow that form. His compositions are pointed by rests, tempo changes, and bursts of sound that the soloists adhere to or soar above. These elements (much like guideposts in the work of Mingus) serve to lock the solos into the larger context of a compositional whole.

Embers stands perfectly well by itself as pure music, but Harris poses some extra-musical purposes: “With this project, I aim to illuminate the EMBERS that quietly burn within the evolving history of our societies — embers of courage, progress, respect, and also of prejudice, inequity, and resistance to change…. I celebrate the strides we have made toward a more just society, while also holding up a vigilant light to areas where progress still falters.” Although we may tend to think of embers as the remnants of dying fires, Harris noted during the Regattabar performance that embers can reignite if given the proper air and fuel — and there is plenty of fire in this new CD.

It consists of five quintet pieces, two trio performances, and three fragments (called “Canvases”) that show Harris trying out short-form ideas with bassist Max Ridley and drummer Tyson Jackson. In the context of a more expansive piece (“Lullaby for a Yellowbird, Lullaby for Humanity”), the three of them create a group music that recalls the intuitive play of Keith Jarrett’s early trio with Charlie Haden and Paul Motian — again, this is not faint praise.

Ridley and Jackson are equally marvels in Harris’s quintet pieces, providing the vitally important sure feet for his ingenious writing. The quintet tunes on Embers are filled with stop-time rests, splashy directional chords, and fluid lines that snake and curl. A lesser rhythm section might sound tentative negotiating these features; Ridley and Jackson never do.

Ridley and Jackson are equally marvels in Harris’s quintet pieces, providing the vitally important sure feet for his ingenious writing. The quintet tunes on Embers are filled with stop-time rests, splashy directional chords, and fluid lines that snake and curl. A lesser rhythm section might sound tentative negotiating these features; Ridley and Jackson never do.

The three front-line voices provide perfect complements to each other in these performances, and they fill out the potential of Harris’s tunes with deep maturity. Jason Palmer, a longtime associate of Harris, is one of the most distinctive trumpeters working today. He draws on speech patterns and puckish half-valving in his playing, and each of his solos seems to be telling a story — a quality that links him to a long line of thoughtful brass players like Art Farmer, Kenny Dorham, Ray Nance, Harry Edison, and others, going right back to Bix Beiderbecke. His solo on “Embers” is just one choice example of his talent. Caroline Davis is just as thoughtful, but in a different way; she is a structuralist, drawing from the architecture of the compositions and then building her own ideas dramatically. She has a softish sound on her axe that recalls Paul Desmond, Johnny Hodges, and Benny Carter; in her thinking more than her sound, she draws on Jackie McLean (but what alto player isn’t influenced by Jackie?). Her solo on “Pendulums” is a model of craft.

The leader, when he becomes a soloist, does not try to dazzle with technique. Instead, Harris fills the role with the same creativity he brings to his writing. He has plenty of speed, but he uses it carefully, for maximum effect. In “Beyond Gravity,” for example, he is thoughtful from the get-go: Ridley is crucial in making his ideas work, and then Harris shows a wealth of excellent thinking all around the melody, leading with almost inevitable logic right back to the closing head.

The CD has the additional pleasure of Terri Lyne Carrington sitting in Tyson Jackson’s chair on “Beyond Gravity” and on a trio piece called “Jim Crow and the Medicine Man.” As she always does, Carrington provides exactly what’s needed to perfect a performance.

Embers will satisfy anyone who loves jazz creativity on a small scale. And you would be wise to grab your tickets early for Harris’s next live date, because his fans are avid, and they fill those chairs.

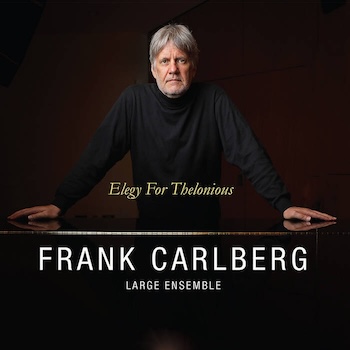

Frank Carlberg’s Elegy for Thelonious (Sunnyside, released in 2024), recorded in 2022 and played by his “Large Ensemble,” is far more than an homage to a composer whose work seems to get more and more significant as the years pass. Carlberg has recomposed five Thelonious Monk tunes here, always respecting the strength and sinew of the originals, but providing some of the most inventive rethinkings of Monk’s music that have ever been recorded.

Frank Carlberg’s Elegy for Thelonious (Sunnyside, released in 2024), recorded in 2022 and played by his “Large Ensemble,” is far more than an homage to a composer whose work seems to get more and more significant as the years pass. Carlberg has recomposed five Thelonious Monk tunes here, always respecting the strength and sinew of the originals, but providing some of the most inventive rethinkings of Monk’s music that have ever been recorded.

The composer-leader is Finnish by birth, a New Yorker as a performer, and a Bostonian by academic connection. Carlberg’s “Large Ensemble” is set up like a traditional big band and draws from the best talent in NYC and here. It has 16 basic pieces, with eight brass, five reeds, piano, bass, and drums, but Carlberg adds depth and color by bringing in two different singers and an electronics gadgeteer.

The more familiar you are with Monk’s music, the more you will be enthralled at what Carlberg does with it. In keeping with Monk’s aesthetic, his compositions may seem a bit thorny at first, but on second and third hearings the thicket clears and his ideas become obvious. Four of the tunes he transforms — “Skippy,” “Locomotive,” “Gallop’s Gallop,” and “Brake’s Sake” — are among the least-frequently-covered of the master’s works. Bravo to Carlberg for taking them on. “Trinkle Tinkle” is better known, but a killer to play; Carlberg’s “abstraction” on it is the most abstract of the pieces here, and the one that requires the most listening.

Each one of the compositions deserves a full discussion, but that is impossible given space restraints. I’ll have to limit myself to “Spooky Rift We Pat.”

The title is an anagram of “Skippy” and “Tea for Two” — the 1924 Vincent Youmans theme that Monk used as his starting point when writing “Skippy” — and Carlberg’s composition uses both melodies. It begins misterioso, and then Christine Correa slides into the music, singing words that seem to come from one of the collage poets à la Steve Lacy:

Raise a family. / I’m discontented. / I’ve invented my own weary peace unknown. / Cozy to hide and to live side by side. / Caress the stream.

But these words aren’t avant-garde at all. Carlberg has taken a cue from Monk and deconstructed Irving Caesar’s lyrics from “Tea for Two,” including its rarely performed verse, to create this collage. Once he establishes a staccato rhythm, he gives Correa more of those words, and we begin to hear the outlines of “Tea for Two” as it’s familiarly heard. Then pieces of “Skippy” begin to be added, but the vocal becomes more and more a series of fragments, seemingly ending in mid-phrase (“Start bake a cake / We raise a fa-“) — but the last words should lead our minds right back to “raise a family,” the first words of the performance.

Then Adam Kolker supplies a strong tenor solo on the changes of “Skippy,” and we hear how good the rhythm section is (Leo Genovese, Kim Cass, and Michael Sarin) as they support him and lead into an edited version of Monk’s theme, which concludes with the inimitable big 8-bar passage that concludes “Skippy.”

But that’s not all. Carlberg then sets up a second section in more open harmony for a solo by trumpeter David Adewumi, and we hear the ensemble play some ideas influenced by George Russell. Finally, the “Skippy” theme gets the full treatment it deserves, but Carlberg tantalizingly holds off its conclusion by repeating one of the two last 4-bar phrases as the basis for Kolker and Adewumi to return improvisationally. The final 4 arrives at last, followed by a lovely coda.

Does it sound complicated? The ideas abound, it’s true, but the flow is irresistible, and the whole thing is shot through with excitement and joy. The same can be said for the four other recompositions. The CD is completed with an original called “Wanting More” (with lyrics repeating one of Monk’s wise aphorisms, “Always leave them wanting more”), and the title composition, which uses elements of “Blue Monk” and a hymn called “Abide with Me” that Monk enjoyed playing.

It is an exhilarating adventure.

If Carlberg’s adventure is extrovert, Jamie Baum’s is equally fascinating, but in an introverted way. Her CD What Times Are These (also released on Sunnyside in 2024) is a fully realized suite of pieces drawing on texts by major poets to reflect on the experience of the Covid pandemic. In her well-written notes, she says she chose “poems that would express not only my feelings during that time [of Covid isolation], but what we were all experiencing socially, politically and emotionally.” She adds, “I wanted to try something new, become submerged, distracted, anything to escape everything going on around me!”

If Carlberg’s adventure is extrovert, Jamie Baum’s is equally fascinating, but in an introverted way. Her CD What Times Are These (also released on Sunnyside in 2024) is a fully realized suite of pieces drawing on texts by major poets to reflect on the experience of the Covid pandemic. In her well-written notes, she says she chose “poems that would express not only my feelings during that time [of Covid isolation], but what we were all experiencing socially, politically and emotionally.” She adds, “I wanted to try something new, become submerged, distracted, anything to escape everything going on around me!”

“Try something new” is not precisely accurate. Since her time as a working Bostonian musician in the ’70s and ’80s, Baum has been experimenting with the combination of voice and music, sometimes using spoken word and sometimes using text as the foundation for sung melody. What Times Are These is a peak in this quest, a mature statement from an artist in full control of her materials, interpreted by a stellar small group.

Two of the pieces here use spoken word, but Baum mostly writes song settings for the poems she has chosen. These are not lieder or art-songs per se. Her vocal lines are written more as music than as sound-painting or illumination of the texts; they are musical compositions that treat words as vital elements. Because of this, the listener would do well to follow the texts she provides in the beautiful accompanying booklet — the experience enriches one’s musical understanding of her work and focuses one’s attention on the poets’ messages.

Baum’s group is called “Septet+” — seven pieces plus the leader, I guess — and she has nurtured this working ensemble into a beautifully functioning chamber orchestra. With her own eloquent work on flute and alto flute, and colleagues playing trumpet, French horn, reeds (tripling on alto, clarinet, and bass clarinet), electric guitar, with a rhythm section including pianist and bassist who double on electric instruments, she has a lot of colors to work with in the basic group. A guest percussionist and four vocal artists round out the personnel for this release.

Baum’s settings show an admirable sense of pace and variety. An intimate, lyrical mood suffuses a piece Baum dedicates to her mother — “My Grandmother Is in the Stars,” on a text by Naomi Shihab Nye, sung gorgeously by Sara Serpa. At the other extreme is the spare funk of “Sorrow Song,” with rap by KOKAYI and then the rapper’s deeply committed recitation of a poem by Lucille Clifton, which also includes a fine solo by Baum on alto flute with electronic chorusing. One more word of praise: for the utterly beautiful French horn playing of Chris Komer and equally beautiful wordless vocal from Aubrey Johnson on “Dreams,” perhaps the most conventional of Baum’s pieces here, if anything this good could be called “conventional.”

Perhaps the heart of the CD, worthy of more detailed parsing, is found in the two pieces with texts by Adrienne Rich.

“In Those Years” is realized with a bit of electronic coloring to showcase the singing of Theo Bleckmann, who has a broad range, from contralto to bass. Baum constructs a prelude for it that recalls the English vocal music of Taverner and Tallis, with Bleckmann overdubbing the words “I,” “we,” and “you,” reflecting a line in the poem (“We lost track of the meaning of we, of you”). Baum’s follow-on music is punctuated with a two-beat stop-time effect, which underpins a creative restructuring of the Rich poem; Baum doubles Bleckmann’s vocal with guitar, brings the electronic chorus back for support midway, and sets up fine solos by Sam Sadigursky on alto and Luis Perdomo on piano, using only spare instrumentation behind them. The piece is rounded out by more of the electronic chorus in the background of the final measures.

“What Kind of Times Are These” is purely acoustic, another feature for Sara Serpa, with one of Baum’s most inspired melodies, a setting that rivals the beauty of Maria Schneider’s writing for voice. Serpa sings with great feeling here, with a central theme of the CD emphasized in a modification of Rich’s words: “because in times like these / because in times like these / to have you listen at all / in times like these / it’s necessary to talk about trees / about trees.” The track has one of several guitar solos by Brad Shepik, whose fuzz-tone approach thickens and enriches the overall effect.

I can cavil a bit about the recitations on the first two poem settings, because Baum and her trumpeter Jonathan Finlayson do the readings there. In comparison with KOKAYI’s deeply felt reading on “Sorrow Song,” these lack a bit of passion, and I was surprised to hear that Baum, a wind player, doesn’t get enough of a column of air under her voice when reading “To Be of Use” by Marge Piercy.

But these are tiny flaws in an otherwise superb collection. I would be remiss here if I did not point out that Mike Holober, whose recent CD (This Rock We’re On: Imaginary Letters) I critiqued sharply in August, is one of the producers of this outstanding project, along with Baum herself and the excellent keyboard player Richie Beirach.

Finally, a musical work that is sui generis, something that I found appropriate to the holidays even though it has barely a hint of Christmas about it. Florian Weber’s Imaginary Cycle: Music for Piano, Brass Ensemble and Flute (ECM, 2024) is a secular liturgy, a collection of pieces arranged in the form of a religious service — intensely spiritual music for an agnostic age. Improvisation is essential to this music but not central to it. It could not exist without jazz, but jazz is only one of 10-plus influences that Weber brings together — I hear ancient hymnody, medieval choral music, Bach, George Gershwin’s “The Man I Love,” Bill Evans, Claude Debussy, Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo vamp, Conlon Nancarrow, and moments with a vaguely Christmas-y vibe; you may hear more.

In almost every aspect, this is a collection of original ideas. The ensemble has three principal voices — piano (Weber), flute (Anna-Lena Schnabel), and tuba (Michel Godard, who also doubles on the ancient wind instrument called serpent). The support is provided entirely by eight low brass instruments — four women trombonists who have some experience in contemporary improvisational music, and an organized quartet of French euphonium players who come from a traditional classical background. Finally, the producer has an unusually prominent role. Manfred Eicher, the guiding light of ECM Records for 55+ years, suggested a larger ensemble and a particular acoustic to Weber, ideas which the composer embraced. Weber says that his concept “started out from a piano-centric approach. Manfred [Eicher] introduced the idea of having other instruments join in, but from afar.” In the recording, we hear the brass support players positioned at an acoustic distance, but still heard with clarity. The idea must have taken considerable studio time to refine, but it works very well.

The music consists of 17 individual pieces, each of which provides a satisfying statement on its own. But Weber intends them to be appreciated as a suite, and the collective impression of the work is much more than the sum of its parts. Perhaps I’m being overly simple, but I believe this is accurate nonetheless: it casts a spell.

A prelude and epilogue frame the suite proper, which Weber organizes into four sections, “Opening,” “Word,” “Sacrifice,” and “Blessing.” Christians will recognize these sections corresponding to the traditional form of Sunday worship, from the Catholic Mass to the most austere Protestant sect. Weber says it is “a transfigured Mass, stripped of its dogmatic structure and expanded with the improvisational language of more modern designs.” “Word” could be interpreted as referring to gospel reading, but I think Weber intends it to be a reference to preaching; Anna-Lena Schnabel (flute) and Michel Godard (tuba) have their moments to preach in this section, and each is eloquent.

The composer’s piano contributions always sound authoritative, even if he is not “soloing” in the traditional sense. Some of his work is undoubtedly improvised, but it is so well integrated into the overall structures that one does not hear it as something independent. One of his most prominent statements is in the fourth movement of “Word.” After Schnabel and Godard have preached on flute and tuba in the second and third movements, Weber has his say. At first he is modal and mysterious, then more evocative of rippling water. The brass appear behind him, declamatory. Weber has another piano passage, and then the brass introduce a theme that recalls ancient hymnody, very beautiful. Weber decorates this with piano figures as the music moves to a long sustained brass chord at the end.

Pianist Florian Weber. Photo: Christoph Bombart

I find some of the most remarkable moments in “Sacrifice,” which, after all, is the heart of the Christian liturgy. The third movement spotlights Godard’s serpent in conversation with Weber’s piano. It appears to be an improvised duet with musical “guideposts,” veering to and from “The Man I Love” in its second section. The last movement brings Schnabel to the fore. Weber’s piano is dark and questioning in the first section, perhaps peering into the abyss and finding something unsettling. A somber piano chord ushers in the flute, very active, with many glisses and interesting effects, including some vocal additions. The piano returns in a similar questioning mood, with the flute in duet. The brass come in under, and the entire ensemble moves to a sense of elevation and then conclusion. By this moment in the suite, it may be impossible to think of this music without attributing some sort of religious framework — is this the questioning believer being reassured by the Holy Spirit?

When the impact of a recording is so distinctive and spiritual, it is a bit unsettling to have it accompanied by an intellect-heavy liner note. This one comes from Friedrich Kunzmann, who hosts podcasts for ECM, and its English translation includes some welcome observations by the composer. But Kunzmann’s own appreciation is mired in logorrhea. At one point he describes the experience of the work as “polyphonic intuition … [when the] consciousness of listeners and players is put into a purely intuitive state by the simultaneity of musical events.”

But this is what jazz does every day, and it hardly needs multisyllabic explanation.

Even though each of the four releases here draws on jazz to succeed in its designs, none of them should be misunderstood as limited by that connection. Each of them reaches for the stars; I was glad to be along for the rides.

… so why do I tell you anything? / Because you still listen … — Adrienne Rich

Discographical details:

Kevin Harris Project: Embers (Kevin Harris Project, 2024) Rec. Manhattan, NY, probably 2024. Produced by Kevin Harris. Harris, p; Jason Palmer, tp; Caroline Davis, as; Max Ridley, b; Tyson Jackson, dm (replaced by Terri Lyne Carrington on “Beyond Gravity” and “Jim Crow and the Medicine Man”)

Frank Carlberg Large Ensemble: Elegy for Thelonious (Sunnyside, 2024) Rec. May 2022, Brooklyn, NY. Produced by Frank Carlberg. Carlberg, cond; 8 brass (4 cnt/tp/flug, 4 tb/btb), 5 reeds (fl/cl/bcl/as/ts/bari/lyricon), Leo Genovese, p/synth, Kim Cass, b, Michael Sarin, dm; Rahul Carlberg, elecs; Christine Correa, Priya Carlberg, vo

Soloists: Kirk Knuffke, cnt; Savid Adewumi, tp; John Carlson, tp; Brian Drye, tb; Nathan Reising, as; Jeremy Udden, as / lyricon; Adam Kolker, ts; Hery Paz, ts

An FYI key to the titles: “Spooky Rift We Pat,” as noted above, is based on “Skippy” and “Tea for Two.” “Out of Steam” is based on “Locomotive.” “Scallop’s Scallop” is based on “Gallop’s Gallop.” “Wrinkle on Tinkle” is based on “Trinkle Tinkle.” “Brake Tune” is based on “Brake’s Sake.”

Jamie Baum Septet +: What Times Are These (Sunnyside, 2024) Rec. Apr 2023, Mt. Vernon, NY. Produced by Jamie Baum, Richie Beirach, & Mike Holober. The Septet+: Jamie Baum, fl, al-fl, recit; Jonathan Finlayson, tp, recit; Sam Sadigursky, as, cl, bcl; Chris Komer, FrH; Brad Shepik, g, singing bowls; Luis Perdomo, p, e-p; Ricky Rodriguez, b, e-b; Jeff Hirshfield, dm

Guests: Theo Bleckmann, Sara Serpa, Aubrey Johnson, vo

KOKAYI, rap, vo, recit; Keita Ogawa, per

Florian Weber: Imaginary Cycle: Music for Piano, Brass Ensemble and Flute (ECM, 2024) Rec. Bremen, Germany, July 2022. Produced by Manfred Eicher. Florian Weber, p; Anna-Lena Schnabel, fl; Michel Godard, tu, serpent; Lisa Stick, Sonja Beeh, Victoria Rose Davey, tb; Maxine Troglauer, btb; Quatuor Opus 33 [Corentin Morvan, Jean Daufresne, Patrick Wibart, Vianney Desplantes], euph

Kevin Harris Project’s website

Frank Carlberg’s page from the MacDowell Colony website, with a biography

Jamie Baum’s Septet+ page from her website

Florian Weber’s website

Carlberg’s Elegy for Thelonious and Baum’s What Times Are These are available through Bandcamp. Sunnyside Records deserves a special tip of the cap for releasing both of these fine recordings in 2024.

I am very grateful to Bruno Råberg for recommending Frank Carlberg’s Elegy for Thelonious. Perhaps there is no greater compliment that can be paid than one artist of stature pointing to another and saying, “You’d better hear this guy.”

Finally, I recommend hearing Adrienne Rich’s own reading of her poems “What Kind of Times Are These” and “In Those Years,” along with a discussion of her intentions and ideas as part of a conversation with Bill Moyers.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.