Critical Homage: A. Alvarez — Beyond Fiddling Away

By Bill Marx

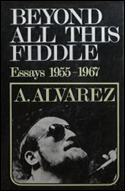

Al Alvarez’s new book of essays provides an opportunity to also strongly recommend his first collection of literary commentary and reviews, 1969’s Beyond All This Fiddle, one of the most invigorating collections of cultural commentary from that period.

The latest issue of the TLS features an irritatingly short review of Risky Business, a new gathering of essays on “people, pastimes, poker and books” by the fine critic, novelist, and poet Al Alvarez. Best known for his book on modern poetry, The Shaping Spirit, and the sometimes hysterical analysis of Sylvia Plath, The Savage God: A Study of Suicide, Alvarez occasionally takes up subjects that aren’t of much interest to me, such as gambling and rock climbing. (Those interested in his rebellion against the contemplative should turn to his enjoyable 1999 memoir Where Did It All Go Right?) Fortunately, along with his intense meditations on nerves of steel, Risky Business includes pieces on, among others, Plath, the Polish poet Zbigniew Herbert, Seamus Heaney, Jean Rhys, and Malcolm Cowley.

The appearance of this book gives me an opportunity to recommend it and Alvarez’s first collection of essays, 1969’s Beyond All This Fiddle, which is sadly out of print. It is one of the most invigorating collections of cultural commentary from that period, holding up better than ballyhooed volumes by Susan Sontag and other camp hipsters of the time. The volume features a sympathetic yet skeptical mind in the thick of things, trenchantly evaluating some of the artistic transformations and misfires of the ’60s, forcefully calibrating changes for the better and the worse. And that is why the volume hasn’t dated as badly as other reports from the front who jumped on the bandwagon of the “far out.”

Also, Alvarez is alert to the fear, as well as the promise, at the center of a period of transition, when “the electronic culture threatens to shatter all the traditional disciplines which are worked so hard for and acquired only slowly and with such difficulty.” For him, the antique discipline practiced by the best critics builds a world of values out of literature: “Inevitably they don’t like much, for in all visible moralities the elect are, of necessity, few. So their work is devoted to keeping up standards, always with an intellectual passion, sometimes with a certain savagery. Like old-fashioned doctors, they believe that blood must at times be let to preserve the health of the patient.” Ironically, the popular brand of new-fashioned medicine practiced by most of today’s arts critics amounts to “doing no harm” until the patient expires.

The reviewer-doctor administers some wounds, slashing at theater critic Ken Tynan (“It is as though Tynan inhabited a world in which haute cuisine and politics were equal and interchangable”), art critic John Berger (“For all his brilliance, Berger is a sentimentalist, and what he sentimentalizes above all is the ideal of solidarity”), Norman Podhoretz, and, of course, the faddish Sontag (“It is as though she felt she had to justify her enjoyment of things lowbrow by a sophisticated double-take which proves that, in the last analysis, what is terrible is good, since boredom is the only interesting emotion left.”).

Alvarez not only bitingly sizes up his contemporaries, but also provides plenty of admirations, spreading his thoughtful praise over an impressive range of writers and books from John Dryden and John Keats to Miroslav Holub, Piotr Rawicz, and Patrick White.

Here is one of my favorite passages from Alvarez’s essay “The Limits of Analysis”:

“The one demand that can reasonably made of the critic is that he be original. In the last analysis, it doesn’t matter if he is right or wrong, bigoted or generous, narrow-minded or catholic, provided he says his own say, gets his own feelings straight and sets up his own standards for inspection and, if necessary, for disagreement; provided, that is, he creates his own moral world with as much intelligence he can muster. And this is the most fundamental form of commitment; it is not a matter of political dogma or accepted standards, but of the life of the man linking creatively with the life of the work.”

Also worth bearing in mind, from the same essay:

It is the business of the pedagogues to be useful, but it is the business of the critics to be lucid… For it is lucidity. not complexity, that is the final token of intelligence and honesty.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: 60s, Al-Alvarez, Books, beyond-all-this-fiddle, criticism, risky-business