Jazz Album Review: Ohad Talmor’s “Back to the Land” — Homage to Ornette Coleman

By Michael Ullman

We should be grateful for Ohad Talmor’s wide-ranging curiosity, not only because of the detective work he put into the Ornette Coleman/Lee Konitz recordings, but because of his uniquely varied presentations of these mostly unknown pieces.

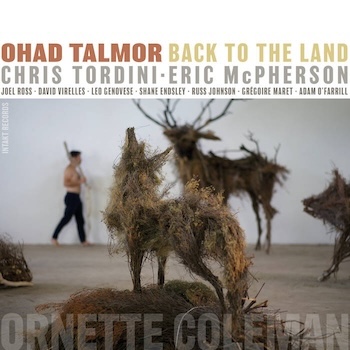

Ohad Talmor, Back to the Land (2 CDs, Intakt Records)

Born in 1970 and raised in Geneva, the peripatetic saxophonist Ohad Talmor attended high school in the United States and subsequently studied musicology at the University of Geneva. He is best known in this country for his recordings with Steve Swallow and for his many enterprising collaborations with his mentor, Lee Konitz: these include big band arrangements, small groups, and his writing/arranging for the session that became Konitz’s New Nonet. The pair were nothing if not ambitious: I’ve just listened to Lee Konitz and the Axis String Quartet Play French Impressionist Music from the 20th Century. Talmor did the arrangements (and some of the composing) in these treatments of pieces by Debussy, Ravel, and Fauré.

Born in 1970 and raised in Geneva, the peripatetic saxophonist Ohad Talmor attended high school in the United States and subsequently studied musicology at the University of Geneva. He is best known in this country for his recordings with Steve Swallow and for his many enterprising collaborations with his mentor, Lee Konitz: these include big band arrangements, small groups, and his writing/arranging for the session that became Konitz’s New Nonet. The pair were nothing if not ambitious: I’ve just listened to Lee Konitz and the Axis String Quartet Play French Impressionist Music from the 20th Century. Talmor did the arrangements (and some of the composing) in these treatments of pieces by Debussy, Ravel, and Fauré.

Konitz was indirectly the inspiration for Talmor’s two-CD collection Back to the Land. The saxophonist tells us in his notes that the project partially followed the discovery of three tapes found in Lee Konitz’s effects after his death in 2020. The tapes contained a 1998 recording of two master alto saxophonists — Ornette Coleman and Konitz — informally rehearsing in Coleman’s loft. Talmor elaborates: “It was Ornette and Lee together with Charlie Haden and Billy Higgins, rehearsing all this new music that Ornette had just written for an upcoming concert…. They’re playing, stopping, talking about women, talking about reeds, things like that.” (Only a saxophonist would consider reeds and women comparable subjects for conversation.)

Talmor began to “make some assumptions” about this music, on tape and in incomplete, fluid form. Sometimes Konitz played the material one way and Coleman another. The result: Talmor came up with versions of 10 unknown, untitled Coleman tunes, and they form the core of Back to the Land. Added to these new tunes are several Ornette pieces (from other recordings) and Talmor originals, including the title cut. On top of that, he pays tribute to another saxophone mentor, Dewey Redman, with a pair of tracks — Redman’s “Dewey’s Tune” and “Mushi Mushi”. If I am hearing the tune correctly, the latter, though copyrighted by Redman, goes back a little further. Redman’s version, heard on Keith Jarrett’s Bop-be, seems to be a variation on Herbie Mann’s “Mushi Mushi,” which the flutist recorded at the Village Gate in 1965 and issued on the disc Standing Ovation at Newport. (Labeling on records wasn’t always accurate: the Village Gate is obviously not Newport. On the Bop-Be album, bassist Charlie Haden’s name is misspelled as Hayden.)

Saxophonist/composer/arranger Ohad Talmor. Photo: Bandcamp

Talmor elaborates on his handling of the Coleman tunes: “All the pieces at some point are played trio in their purest form in very short three-minute versions, theme and variations. ‘Tune 4’ was given a new life with the four sextet variations, and the same thing with the septet on ‘Tune 1.’ Sometimes I added chords when I heard chords; other tunes were heavily reappropriated in an electronic environment.” This saxophonist/composer is his own man with his own mellifluous sound. Talmor’s playing doesn’t proffer the intense forward motion of Coleman’s, who at times could sound both totally in control and as if he were about to fall down the stairs. Instead of this kind of teetering fierceness, we have 24 lyrical tracks that include the exquisitely wistful beauty of “Tune 10,” whose theme is introduced with a harmonica solo by Grégoire Maret over the bass lines of Chris Tordini. Pianist Leo Genovese supplies an introduction that sounds as if it was from a soundtrack for the beginning of a French movie.

On “Tune 10,” Talmor’s gently probing solo is confined to the upper range of the tenor. He doesn’t sound like either Coleman or Konitz. His trio version of “Tune 1” is dreamy in a way that Coleman never was. Talmor adds variety to this collection by arranging some of the same tunes for different configurations. He brings in special guests. “Dewey’s Tune” opens with Joel Ross’s vibraphone solo, for instance. Talmor can evoke the Coleman spirit when he wants: “New York” opens with a bass solo whose calm use of space reminds this listener of Charlie Haden. The tune is taken from Coleman’s album Prime Time/ Time Design.

On the album’s second disc, Talmor plays with electronics. His “Astonishment” kicks off with a jumble of hissing/sissing sounds that soon leads to a conversation between prerecorded electronics and bass. It gives way to one of the most Coleman-sounding pieces, “Trio Variations on Tune 2.” Then we return to dollops of electronics on “A Good Question.” Variety is very much the spice of musical life for Talmor. We should be grateful for wide-ranging curiosity, not only because of the detective work he put into the Coleman/Konitz recordings, but because of Talmor’s uniquely varied presentations of these mostly unknown pieces. He adds in the notes that the piano recorded on Back to the Land was previously owned by Konitz. Fittingly, it landed with Talmor.

For over 30 years, Michael Ullman has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. He has emeritus status at Tufts University, where for 45 years he taught in the English and Music Departments, specializing in modernist writers and nonfiction writing in English, and jazz and blues history in music. He studied classical clarinet. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: "Back to the Land", Adam O’Farrill, Chris Tordini, Denis Lee, Eric McPherson, Grégoire Maret, Ohad Talmor, Ornette Coleman