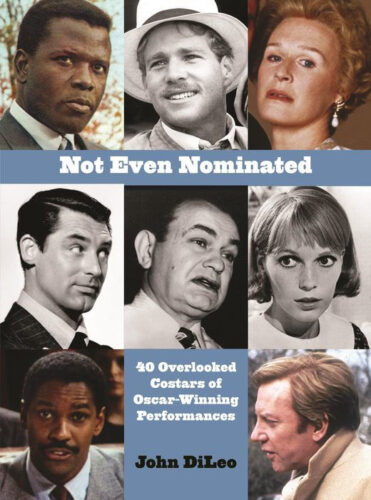

Book Review: “Not Even Nominated” — They Shoulda Been Oscar Contenders

By Robert Steven Mack

Critic John DiLeo argues that even the Academy Awards can make mistakes. And, in the process, he constructs an alternate history of who should or should not have been Oscar nominees.

Not Even Nominated: 40 Overlooked Costars of Oscar-Winning Performances by John DiLeo. G Letters, 320 pages, $33.25.

Ostentatious gowns, slick comic monologues, an occasional streaker — the glitzy happenings at the Academy Awards ceremony have made it one of America’s cultural touchstones. For many, the prizes the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences hand out are the last word in movie excellence. Film critic John DiLeo’s book Not Even Nominated: 40 Overlooked Costars of Oscar-Winning Performances begs to differ. He shows that even the Academy Awards can make mistakes. And, in the process, he constructs an alternate history of who should or should not have been Oscar nominees.

DiLeo’s main line of attack focuses on how “showier” performances steal the attention from subtler and more nuanced turns. He takes readers from the first Oscar ceremony in 1928 to 2015, highlighting under-appreciated performances in both well known classics and less remembered gems. DiLeo compares the winning performances in the films with their unnominated costars. His aim is not denigrate the winning actors or to assert that his picks should necessarily have won. His mission is to give great pieces of acting their due — when the Academy didn’t.

Sometimes DiLeo finds two actors equally responsible for the success of a film where only one was singled out. For example, James Stewart received an Oscar for 1940’s The Philadelphia Story while co-star Cary Grant wasn’t even nominated. Grant played the straight man to a more broadly comic Stewart, but the comic electricity is generated by the way they play off of each other. Grant delivers an integral performance, alternating effortlessly between charmingly smug humor and his genuine passion for Katherine Hepburn’s character. DiLeo notes that, surprisingly, Grant never won a competitive Oscar; he was only nominated twice, for the forgotten dramas Penny Serenade (1941) and None But the Lonely Heart (1944). Even when he thrived taking on a darker role, in Alfred Hitchcock’s Suspicion (1941), Grant went unrecognized until the Academy granted him an honorary Oscar in 1970, after he had already retired.

DiLeo also makes an excellent case for Gregory Peck’s performance opposite Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday (1951). Although Peck would win for his celebrated portrayal of Atticus Finch in 1963’s To Kill A Mockingbird, DiLeo argues that Peck deserves another look as the newspaper man who ends up spending the day with Hepburn’s Princess Ann, who has snuck out of her isolated palatial digs to spend one day as a regular girl in Rome. Audiences were no doubt dazzled by newcomer Hepburn as a reverse Cinderella, but Peck’s character gives the film much of its dramatic weight. His jaded outlook on life is subtly adjusted over the course of 24 hours with the Princess.

Captains Courageous: Freddie Bartholemew, rather than Spencer Tracy, should have been nominated for an Oscar.

In fact, DiLeo argues that the Oscars often overlook performances in which the actor is playing a character whose arc is integral to the plot. For example, he convincingly notes that young Freddie Bartholemew’s spoiled child, who undergoes a heartfelt transformation in 1937’s Captains Courageous should, have been nominated rather than Spencer Tracy, who gives an endearing but admittedly mannered performance as the sailor Manuel. In another instance, Sidney Poitier may have won Best Actor for his iconic Virgil Tibbs in 1967’s In the Heat of the Night, but Rod Steigers’ racist police chief undergoes a more challenging transformation.

DiLeo insists that the performers in some roles are overshadowed by their more iconic counterparts.Julie Andrews won for the title role as Mary Poppins (1964), but DiLeo wonders why the Academy did not pay more attention to David Tomilson as George Banks. Andrews was so “practically perfect” as Poppins that her character never developed throughout the film. DiLeo makes the case that the film revolves around Tomilson’s Mr. Banks, who learns how to prioritize his children over his job. DiLeo neglects to mention that Tomilson’s Mr. Banks served as the prototype for all the Dads in ’90s comedies who learned the value of spending more time with their children.

In a number of cases, DiLeo finds impressive younger costars overshadowed by more established actors. For instance, DiLeo points to Johnny Depp, who is overlooked as the earnest yet hopelessly untalented film director in Tim Burton’s Ed Wood (1994). In this case I disagree: winner Martin Landau was more touching as Bela Lugosi, the dying actor who originated the film role of Dracula. DiLeo writes that the 21-year-old Kim Darby was ignored in favor of an aging John Wayne in True Grit (1969) — though he concedes that Wayne’s win was a consolation prize for not winning for 1948’s Red River, 1949’s She Wore a Yellow Ribbon, or 1956’s The Searchers. The critic correctly admits that John Wayne doesn’t always just play John Wayne. He also contends that amiable Ryan O’Neal was unfairly passed over in favor of his eight-year old daughter Tatum O’Neal in 1973’s Paper Moon.

Actors that play the riskier or more “shocking” roles often have an Oscar edge. Tom Cruise’s Charlie Babbitt faded put up against Oscar-winner Dustin Hoffman’s autistic titular character in 1988’s Rain Man. Another is Jeff Bridges’ Jack Lucas, thrown into the shadow by Robin Williams’ admittedly impressive portrayal of a psychotic homeless man in Terry Gilliam’s haunting The Fisher King (1991). DiLeo also suggests that Tom Hanks’ Oscar-winning performance as a gay man dying of AIDS in 1993’s groundbreaking Philadelphia overshadowed Denzel Washington’s less “risky,” but still nuanced, performance as the homophobic lawyer who defends him.

Other times the Academy simply takes more restrained performances for granted, such as the perennially underrated Myrna Loy in The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). Loy was known for playing intelligent women like Nora Charles in The Thin Man series, yet she never won a competitive Oscar. In The Best Years … she plays the wife to Oscar-winner Frederic March, one of three soldiers in the movie who come home after WWII and have a hard time adjusting to civilian life. Loy, as the quietly strong housewife, provides one of the movie’s most grounding performances. DiLeo particularly admires the scene in which March’s character returns home and surprises his family. As he comes through the front door, Loy is in the kitchen, her back turned to the camera. We can tell — simply by a subtly sensitive straightening of Loy’s back — that she realizes that her husband has returned from the war.

Maggie Smith and Rod Taylor in The V.I.Ps.

As compelling as DiLeo can be, he sometimes tries too hard to defend heartfelt performances that simply aren’t the main draw of the movie. Take the Richard Burton-Elizabeth Taylor drama The VIPs (1963) — the critic is correct that a young Maggie Smith is fascinatingly restrained as Miss Mead, a secretary pining after Rod Taylor’s industrialist Les Mangum. But, compared to the comic theatrics of winner Margaret Rutherford as a cash-strapped Duchess — essentially rehashing her lovable Miss Marple, I admit — Miss Mead fades into the background. I was more moved when the Duchess miraculously resolved her cash problems than when Miss Mead finally got Mangrum to notice her. Another instance: I get why DiLeo lauds Edward G. Robinson as the gritty gangster Johnny Rocco in 1948’s Key Largo, but Claire Trevor steals the show as Rocco’s alcoholic girlfriend, achingly belting out her old nightclub song in exchange for just one drink. There’s no question hers was the stand out performance deserving of the Academy’s recognition.

But it is the book’s multiple invitations to argue rather than agree that makes Not Even Nominated ideal for classic film buffs, particularly those who want to come up with their own alternative list of Oscar nominations. Besides that, DiLeo will no doubt introduce readers to superb films that they had missed; he will also encourage a fresh look at familiar performances. At every Oscar ceremony somebody (perhaps more than one) walks out at the end, muttering under their breath that “they wuz robbed.” Here’s a long overdue book for them and their sympathizers.

Robert Steven Mack is a Southern California-based ballet dancer and filmmaker. He has also contributed to The New Criterion, Law and Liberty, and American Purpose, holds a Master of Public Affairs from the O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs, a BA in History from Indiana University, Bloomington, and a BS in Ballet Performance from the Jacobs School of Music.

Tagged: "Not Even Nominated: 40 Overlooked Costars of Oscar-Winning Performances"