Classical Album Reviews: Eric Coates Orchestral Works, Vol. 4, and Prokofiev Orchestral Works

By Jonathan Blumhofer

John Wilson and his players clearly have the measure of Eric Coates’ tuneful, often clever, style and deliver it to the hilt; Aziz Shokhakimov and the Strasbourgers, though still on a learning curve, have a bright future ahead of them.

“Especially in Germany,” Anne-Sophie Mutter told me a couple of years ago, “there’s this way of thinking [about music…being] either ‘serious’ or ‘light.’ And that sort of boxed thinking is really highly damaging.”

“Especially in Germany,” Anne-Sophie Mutter told me a couple of years ago, “there’s this way of thinking [about music…being] either ‘serious’ or ‘light.’ And that sort of boxed thinking is really highly damaging.”

As if to underline Mutter’s point, John Wilson and the BBC Philharmonic have been busy these last several years simply ignoring such distinctions. To wit: their survey or the orchestral music of Eric Coates (1886-1957). Back in 2019, I reviewed the first installment of this set; now, the pairing’s up to Volume Four.

This latest one is, in many regards, not all that different from its predecessor. The BBC Philharmonic’s playing is polished and secure. Wilson and his players clearly have the measure of this music’s tuneful, often clever, style and deliver it to the hilt.

Most of the disc’s seven selections are dances – Coates, as Richard Bratby’s excellent, informative liner notes tell us, loved nothing more than a night out on the dance floor with his wife – and his expertise with the waltz genre is frequently on display. Rarely do Coates’ emerge so melancholy as, say, Josef Strauss’s. Rather, the English composer’s conception of the form is brighter and busier, sounding like a decidedly urbane, mid-20th-century update.

Often, too, they involve more than a little bit of counterpoint. Footlights, a charming “concert valse” from 1939, rarely passes up the opportunity to showcase a countermelody or two. Neither does the thoroughly sophisticated “Evening in Town” of From Meadow to Mayfair, a suite of three lilting movements from 1931.

At the same time, Coates’ technical skill is never fusty or dry. He was a composer who hardly ever seems to have met a tune he couldn’t elevate, be that the central theme in a jaunty curtain-raiser like Music Everywhere or a limpid, sentimental ballad like I Sing to You, the last an instrumental morale-builder composed for the BBC in the opening months of World War 2.

On occasion, Coates’ facility got the better of him. The Four Centuries Suite, an overview of dance forms from the 16th through 20th centuries, is a bit stiff over its first three sections. Then comes the finale, a cheeky, spry, neo-Gershwin earworm (called, appropriately enough, “Rhythm”), that blows everything before it out of the water.

More typical is The Three Bears, a birthday present for the composer’s four-year-old son, that relates the story of Goldilocks in a concise nine minutes. For thematic directness, instrumental sophistication, and wit – “Enter the Three Bears” sounds a bit like a cross between Ein Heldenleben and Charles Gounod’s Funeral March of a Marionette – it’s riotous fun.

Wilson and his band clearly understand this and play the piece (not to mention the whole album) with a proud, palpable sense of ownership.

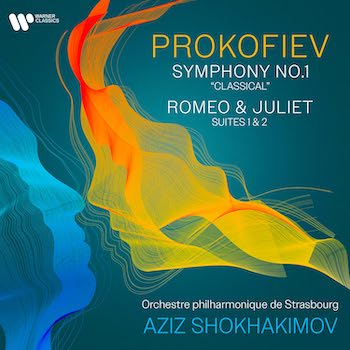

Aziz Shokhakimov’s sophomore effort with the Orchestre Philharmonique du Strasbourg tackles, like the first one did, familiar Russian music. This time, though, the focus isn’t Tchaikovsky but Sergei Prokofiev, whose “Classical” Symphony and suites from Romeo and Juliet stand among the most popular, and canonic, of 20th-century fare.

Aziz Shokhakimov’s sophomore effort with the Orchestre Philharmonique du Strasbourg tackles, like the first one did, familiar Russian music. This time, though, the focus isn’t Tchaikovsky but Sergei Prokofiev, whose “Classical” Symphony and suites from Romeo and Juliet stand among the most popular, and canonic, of 20th-century fare.

The most consistently satisfying performance belongs to the Symphony, whose droll, vivacious spirit comes out strongly. Rhythms, articulations, and tempos are well-judged and uniform. Textures, too: the score’s playful inner voices emerge winningly and the first movement’s noodling, woodwind 8th-note figures seem to anticipate Philip Glass and early John Adams.

Shokhakimov’s readings of the first two suites from Romeo and Juliet boast similarly lean voicings and balances. The “Balcony Scene,” for instance is highlighted by some delicate harp and wind figurations, as well as lush string glissandos, while “Masks’” turns are tight and the ticking figures in “Romeo and Juliet at Parting” are nicely colored.

Yet some spots underwhelm. The “Balcony Scene’s” lyrical climaxes want for fervency while the coda of the “Death of Tybalt” is monodynamic (for comparison, listen to what Michael Tilson Thomas did with that). Likewise, “The Montagues and Capulets” offers little sense of mystery or urgency.

Though the interpretations’ cumulative results are mixed, the pairing’s attention to the finer details of the music – evinced, say, in the flawless balance of the last chord of “Romeo at Juliet’s Grave” – are impressive. If nothing else, they suggest that Shokhakimov (who’s just 35) and the Strasbourgers, though still on a learning curve, have a bright future ahead of them.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Aziz Shokhakimov, BBC Philharmonic, Chandos, John Wilson, Orchestre Philharmonique du Strasbourg