Book Review: “The Work of Art” — Capturing the Experience of Creativity

By John R. Killacky

Adam Moss’ book is an inspiring compendium of interviews and profiles of 43 creatives on how they make their work, using iconic examples to illuminate their process.

The Work of Art: How something comes from nothing by Adam Moss. Penguin Press, 431 pages, $45

Last week I was artist-in-residence at The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia developing ideas for an interdisciplinary installation for an exhibition this fall. I am primarily a filmmaker and got to experiment with a very talented studio production team. A rare and precious opportunity indeed.

Last week I was artist-in-residence at The Fabric Workshop and Museum in Philadelphia developing ideas for an interdisciplinary installation for an exhibition this fall. I am primarily a filmmaker and got to experiment with a very talented studio production team. A rare and precious opportunity indeed.

Accompanying me was a perfect book, Adam Moss’ The Work of Art: How something comes from nothing. The writer, former editor of New York magazine and The New York Times Magazine, interviews 43 creatives on how they make their work, using iconic examples to illuminate their process.

His aim: “to render the experience of creativity – that is, the frustration, elation, regret, first glimmers, second thoughts, distress, and triumph that leads to works of art.” Conversations are augmented with notebook entries, napkin doodles, early sketches, reams of false starts, iPhone photos, lyric fragments, and other ephemera illustrating the alchemical process of artistic conjuring.

Tenacity and resilience abound throughout the beautifully designed compendium. Author Michael Cunningham shares multiple drafts of what became his Pulitzer Prize winning The Hours and we see 39 iterations for a single canvas by Amy Sillman.

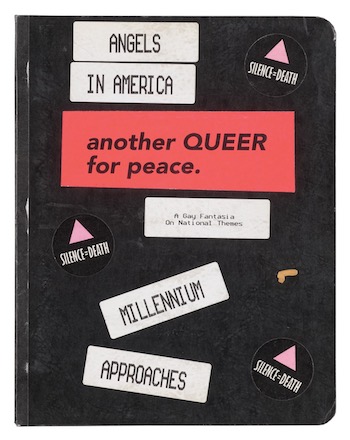

Tony Kushner details free associations, chance happenings, practical constraints, and deep listening to his characters (“I was just taking dictation”) as Angels in America develops. The late poet Louise Glück mentions lines appearing in dreams or fragments scribbled during faculty meetings, only to be fleshed out during long walks.

Cartoonist Roz Chast keeps a shoebox of “idea germs” to draw upon and choreographer Twyla Tharp uses her “sperm bank” of archival videos. Others hack their own systems. Visual artist Kara Walker began one project by drawing with her feet: “I can’t trust this hand not to make something very obvious, that we already know.”

The late Stephen Sondheim recalled dropping a song from Company for its out-of-town tryout and having one week to come up with “Getting Married Today.” Fashion designer Marc Jacobs reiterates the pragmaticism of deadlines: “Time becomes the greatest editor. The only way to get things done is to finish.”

Backstories by pioneering journalists are quite satisfying. Gay Talese’s meticulous and colorful outlines of his travails of never getting to interview Frank Sinatra for his 1966 Esquire piece “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold” sheds light on the what it takes to produce exemplary feature writing.

Excerpts from Wesley Morris’ discursive “My Mustache, My Self” 2020 essay in The New York Times on Black identity and masculinity elucidates why he has been awarded two Pulitzer Prizes in criticism. Fun too are his snippets culled from notes written in the dark while viewing films.

The cover of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America notebook. Photo: Penguin

Architectural inspirations are also provided. Frank Gehry’s initial scribble for the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao opens the book, and in later pages Elizabeth Diller describes the conception of her firm’s Blur Building, which was inspired by airness of water. Like others in the book, she affirms the importance of doodling, as it “imprints something in my brain.”

As a filmmaker, I was particularly heartened to read Andrew Jarecki reminding us that, despite the value of storyboarding, “the footage suggested its own path” and Sofia Coppola’s advice: “…when you have an instinct to do something, you shouldn’t doubt yourself – go with it.”

Other photographers, chefs, puzzle masters, songwriters, radio hosts, sculptors, and graphic designers complement the treasure-trove. And the appendix is chock-a-block full of glorious artifacts from Bob Dylan, Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and other aesthetic forbearers.

The culminating chapter is Suzan-Lori Parks discussing Plays for the Plague Year. Unlike her Tony award-winning Topdog/Underdog, which was written in three days, this episodic theatrical work began during Covid lockdowns and took over two years to come into being. Despite the struggle, she is grateful: “But we are lucky enough to do what we enjoy right? Even if it is hard.”

As for my residency at The Fabric Workshop and Museum, each day brought new possibilities to explore with the production team. All the while, stories from The Work of Art encouraged me to contribute to a collaborative environment of play, creative investigation, and trusting the process.

John R. Killacky is the author of because art: commentary, critique, & conversation.