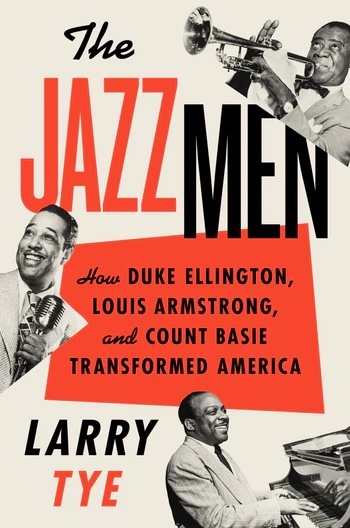

Book Review: “The Jazzmen” — Three Private and Public Lives, Intertwined

By Steve Provizer

In this book, readers are given a full taste of the lives of three complicated musical artists.

The Jazzmen by Larry Tye. Harper Collins, 416 pages.

A number of books assemble short bios under one heading: Greatest Swing Trumpet Players, Best Bop Bassists and the like. What’s unusual about The Jazzmen is that — under one cover — it presents fairly exhaustive biographies of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie. Of course, the question immediately arises of what might be missing.

A number of books assemble short bios under one heading: Greatest Swing Trumpet Players, Best Bop Bassists and the like. What’s unusual about The Jazzmen is that — under one cover — it presents fairly exhaustive biographies of Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, and Count Basie. Of course, the question immediately arises of what might be missing.

First off, this is hardly a Cliff notes version of the lives of these musicians. Given the length of the Bibliography and the copious Notes section, it’s fair to say few stones have been left unturned in gathering information. In addition, author Larry Tye informs us that he conducted 250 interviews of “aging bandmates and friends, relatives and biographers.” No doubt, voracious readers of separate biographies of Armstrong, Ellington, and Basie will notice some omitted information. For example, biographies of jazz performers usually provide lists of gigs as well as some analysis of the performances: the band did so many successful one-nighters through the Midwest, then a disappointing two-week engagement at the Blackhawk, etc. The comings and goings of sidemen is noted more systematically than it is here. Discographic information is also often a part of the package. The Jazzmen supplies this in a scattershot way. If this is the kind of detail you’re after, you will not find it in this book.

That said, this book does what it sets out to do well. Tye organizes the chapters so that he can interweave the lives of his three protagonists: “Setting the Stage,” “Musical Lives,” “It’s an Ensemble,” “Offstage,” “Race Matters” and “Last Acts.” The strength of this method is that the juxtaposition of the information allows for a quick way to compare the lives of his subjects. This is no fault of Tye, but a downside of this approach (for me) was the side-by-side-by-side description of the callous treatment of women by all three men. The sheer accretion of various misogynistic behaviors became slightly depressing.

Overall, it’s difficult to point to any significant biographical matter that’s missing. In fact, the chapter that deals with the musicians’ childhoods supplies some information that was new to me. Ellington’s early self-assuredness is explored. Not only is Armstrong’s brief first marriage described in depth, but his relationship with Lil Hardin looked at from an interesting perspective. The secrets held by Basie’s family foreshadow his lifelong disinclination to talk about his personal life. The trio’s early careers were familiar to me and they are well charted here. I learned new information about Basie’s dissolute behavior and Machiavellian maneuvers in Kansas City.

Tye’s description of drug and alcohol use, friendships, hatred, loyalty and envy proves that life in the Ellington band was anything but dull. Dining in a restaurant meant 15 tables for 15 men. On the other hand, Basie’s band was a tight group that hung together. It’s easy to see why his musicians were loyal to Basie — personnel turnover was small. What’s harder to understand: why so many players stuck with Ellington for decades. Yes, there was a steady (if less than satisfying paycheck) and, oh yea, the music.

Duke Ellington. Photo: Wiki Common

The differences between the public and private personae of the jazzmen are explored. In all three cases, womanizing was successfully kept away from the public, as was Basie’s gambling habit and Ellington’s hypochondria. All three were willing to consort with gangsters, but that was a fairly entrenched aspect of surviving in jazz. Of course, the public presentation of each man was very different. Ellington set himself up as regal; his relationship with audiences was shaped by a “majeste’ persona buttressed by his publicity. Basie was understated; he didn’t even begin to directly address audiences until later in his career. When he did speak, it was like his piano playing — concise. Armstrong, on the other hand, was the consummate all-round performer. Perhaps more than any musician in American musical history, he combined the roles of artist and entertainer. At certain points in his career, this dexterity was not easy for critics — and for his own people — to accept.

All three of these men were complex, but one could argue that Armstrong’s ambiguities were the most public. Did his choice of “Sleepy Time Down South” as his theme song, his smiling persona, and his willingness to be Zulu King in Mardi Gras mark him as an “Uncle Tom”? As a performer, he sweat blood for his audiences, but he sheathed his personal feelings in a demeanor that exuded outgoing, upbeat joy. When Armstrong displaced the Beatles from the charts in 1964 with his version of “Hello Dolly,” the debate ratcheted up.

In the ’60s, I was a typical young jazz fan when it came to my attitude to Armstrong. It was an era of free blowing, Black liberation and Miles Davis turning his back on his audience (or so it was thought). I knew nothing of Armstrong’s foundational musical contributions to jazz or of his staunch, anti-racist positions. After I learned about these things, it was still difficult for me to accept what seemed to be his obsequious mien on white bread television shows (In fact, it was upsetting for me to read in this book about Armstrong’s physical mistreatment of his first 2 wives. One of the reasons the artist/entertainer issue remains thorny is how hard it is to not project what we hear in the music onto the music makers).

The question of artist vs entertainer did not impinge on the career of Basie. As time went on, his band grew to rely on more complex arrangements, but the steadiness of the rhythm section, the power of the horns, and Basie’s pithy piano cues retained the essence of the musician’s sound. Ellington tried to straddle the line between artist and entertainer. Throughout his career he continued to write and perform “tunes.” Revealingly, until the latter part of his career, whenever Ellington stretched the boundaries of his music and wrote longer form compositions, he encountered pushback. His view about this was pragmatic: “The support of the ordinary masses for the music from me, which they like, alone enables me to cater for the minority of jazz cognoscenti, who certainly, on their own, couldn’t enable me to keep my big and expensive organization going.”

Count Basie at the piano performing “One O’Clock Jump.”

There were some revealing stories here that I hadn’t encountered before. Basie trumpeter Harry Edison was arrested for tossing a bagel that knocked a toupee off a guy’s head in a restaurant. In Hollywood, Armstrong performed at Cary Grant’s 38th birthday party: the guests and Grant attended in blackface. Frank Sinatra told his bodyguards in Las Vegas to break the legs of anyone who looked funny at members of the Basie band. Ellington tried to embarrass his musicians, when they were obviously drunk, by making them solo. In response, musicians who felt they weren’t getting enough chances to take the spotlight pretended they were drunk to get more solo time.

Are there gaffes in the book? Not many that I could spot. Tye says Armstrong’s boss Erskine Tate made Armstrong switch “from the cornet to the mellower trumpet,” but it’s the cornet that’s mellower. Armstrong, it is written, recorded “Hello Dolly” for the “relatively unknown Kapp Records.” In fact, David and Jack Kapp were two of the most well-known record producers in the U.S., well situated to handle the distribution of this pop record.

Basie, Ellington, and Armstrong are solidly in the jazz pantheon. They were also roués, at some points blackguards, generous to a fault and, especially as they aged, increasingly religious. Scores of books have been written about all three (fewer for Basie). Not everything one might expect from a conventional biography is here, but Tye’s approach is a very reasonable substitute for leafing through three separate volumes. In The Jazzmen, readers are given a full taste of the lives of three complicated musical artists.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Tagged: "The Jazzmen", Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Larry Tye

I’d be curious to read a comparison of how they each handled the decline of the big band era and the trendiness of bop.

A complicated question, dealt with only peripherally in the book. You had some big band leaders trying to scale down and specifically respond to bop-Artie Shaw, even Goodman. The Herman and Kenton bands were early adopters. Armstrong had already made the switch to smaller groups. He had initial conflicts with the boppers and that settled down but he remained unaffected by the newer music. Basie brought on some soloists that spoke bop and that, along with new arrangements, was part of the change in his sound. Some of what Ellington had been doing for a long time was foundational to bop, but his music remained sui generis.

Monk admittedly took a lot from Ellington’s piano style which, I believe, wasn’t fully recognized until Ellington started doing more trio work in the 1950s. But then there’s Blanton-Ellington recordings from the 1940s.

Re Ellington and bop — I always felt “Cotton Tail” sounds like a bop line