Book Review: “At the Vanguard of Vinyl” — Illuminating and Frustrating

By Steve Provizer

Other readers may be more sympathetic to this informative book’s broader conclusions about the rise of LP’s and the “erasure of black bodies and black aesthetics.”

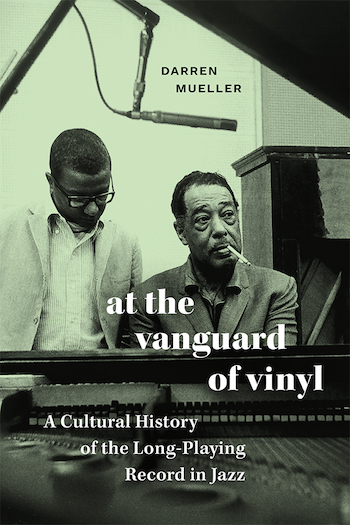

At the Vanguard of Vinyl: A History of the Long-Playing Record in Jazz by Darren Mueller. Duke University Press, 448 pages, $31.95.

The books I read about jazz from the Academy usually demonstrate considerable research, but their illuminating findings are often filtered through an excessively narrow interpretive lens. Not just filtered, really, but at times distorted: the power of the protagonists of the story are attenuated and, by my lights, facts are distorted to fit the Procrustean bed of a grand thesis.

The books I read about jazz from the Academy usually demonstrate considerable research, but their illuminating findings are often filtered through an excessively narrow interpretive lens. Not just filtered, really, but at times distorted: the power of the protagonists of the story are attenuated and, by my lights, facts are distorted to fit the Procrustean bed of a grand thesis.

In At The Vanguard of Vinyl (a title I don’t really understand), author Darren Mueller describes the movement from shellac 78’s to newer formats like the long-playing record (LP) and 45 rpm records. These developments paralleled and, to some extent, were made feasible by the development of recording on magnetic tape. Mueller claims that it has generally been accepted that the process came about much more quickly than it did. He goes on to explain why it took a decade for the LP format to triumph. This is a reasonably interesting premise and he has gathered compelling evidence to support this thesis. However, Mueller interprets these events in a particular way: “…records are the product of social structures and cultural schemas that surround the business and artistic creation of music making. Ideological underpinnings about sound, technology, race, race, gender and performance guide the decisions of record makers.” There is some truth to this, but it should not be accepted as a definitive explanation of a particular person’s behavior in a particular situation. It takes a lot of squeezing, minimizing, and adapting to make this explanation hold water.

For example, Mueller details the editing that George Avakian did on the recording Ellington at Newport. The heart and soul of that 1956 album, which rejuvenated Ellington’s career, was the performance of “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue.” In particular, Paul Gonsalves’s 27 chorus tenor saxophone solo. Gonzalves choose the wrong mic for his solo — technological compensation had to be made. Crowd noise was also added. The author calls his editing intrusive, saying: “Avakian’s various activities in the 1950’s thus expose a particular record making blend of whiteness that centered white male norms and values in iterative fashion…This lens effectively distanced jazz from the broader black popular music by emphasizing the music’s greatness and lasting historical value.” Again, there’s some truth here, but it is unfair to completely characterize this affair as an unalloyed negative, given that the recording resurrected Ellington’s career.

Compare the author’s treatment of Avakian’s editing to how he describes the editing Charles Mingus did on the Jazz at Massey Hall LP (1953). Mingus thought his bass playing was under-recorded, so he overdubbed new bass parts, leaving the old part to ghost in the background. Mueller writes that it is unclear if he let any of his collaborators know of, or approve, his edits. He concludes that it was “a pervasive form of experimentation…his experimentations are a statement about control over his intellectual property…” So, Avakian: intrusive. Mingus: experimental.

Reading this book was a bumpy ride. One page would intrigue or enlighten, the next frustrate, even infuriate. Mueller goes into just how important re-issues were during the initial stages of the development of the LP. They were cheap because old material was available to be repackaged in creative ways. This made me wonder: did the prevalence of re-releases mean that, in live performance, more old material would be performed? Historically, much new material in jazz came from musicals and film. Did the emphasis on marketing old jazz make it more possible for this older body of body to become a canon? Or did the proliferation of jazz recording in toto mean that more “originals” were recorded and performed?

Mueller underlines that the record industry did a lot of experimenting with musical genres in different formats. Record labels chose to feature jazz on LP’s, but tended to release R&B on 78‘s and 45’s. This fits with the points made in Jazz with a Beat, which I recently reviewed. Mueller says the exceptions were the Mills Brothers and Ink Spots — groups with crossover appeal. That said, it was perfectly logical to match jazz with LP’s, given that the length of most jazz performances was well beyond the 3 minute limit of 78’s. Mueller shows there was a concerted effort to cultivate a more upscale demographic that would buy into the higher price point of LP’s. That demographic was largely white and, because jazz worked well on LP’s, a lot of jazz marketing targeted that group. That seems clear. But did this process merely benefit white musicians, as Mueller posits, resulting in the “erasure of black bodies and black aesthetics.”

Mueller spends a lot of time parsing Bob Weinstock’s decision to use words like “new” and “modern” to hype his Prestige Records releases, suggesting that ”adopting such phrasing was also a clever way to brand the inexpensive labor of aspiring musicians eager for their first record deal. That is, this modernist language helped to downplay the capitalist concerns of record making…As was common for white male record collectors interested in the ‘modern,’ Weinstock used this kind of finesse marketing as a form of economic power.” Well, I suppose the producer was guilty of trying to sell records, but I consider this an acceptable tradeoff for the creation of the Prestige Record catalogue, most of which, to my knowledge, features Black musicians.

Weinstock’s efforts, the author goes on to assert, were part of a system that perpetuated a “violent structure of racism meant to exploit Black expertise, Black labor and Black capital…Eurological notions of historical tradition shaped the focus of critical and commercial attention in ways that normalized whiteness.“ Again, one can’t dismiss this point of out of hand: the record industry was and is part of a capitalist and racist culture. But putting it in such stark terms downplays any positive influence the record industry had on the careers of Black jazz musicians. It denies the possibility of the existence of purely altruistic motives, i.e, love of the music and of musicians of any race who played the music.

As noted, the information collected in At the Vanguard of Vinyl is welcome: there’s valuable nuts and bolts about the rise and fall of different recording formats and, at the end of each chapter, lists of representative recordings; there’s an eye-opening look at the skirmish over funding the US Information Agency program, which sent jazz “ambassadors” around the world; and an incisive examination of the role of Celia Mingus in Debut Records. Other readers may be more sympathetic to Mueller’s broader conclusions. For me, subsuming individual motivations to larger ineluctable cultural forces was too hard a polemical pill to swallow.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Whoa. Where to begin. I haven’t read the book, but from this review, it seems there are many holes here. For example, the whole transition from the big bands to small group bop coincided with the slow rise of LPs. The big bands (many, but of course not all, were white) played arrangements specifically geared to the 45 format. The bop groups (many, but of course not all, were black), played longer performances, as you point out, and needed the longer format. And what came between the two were box sets of 45s, approximating the content of an LP. Does Mueller mention those? And what about the less expensive 10-inch LPs, especially the masterpieces produced by Prestige? Or the organized sets of 10-inch recordings? And does Mueller acknowledge that 45s made their companies money not so much by people buying them (white or black, rich or poor) but by being made for jukebox play, which made them accessible to many black communities far away from stores and radio stations?

If this is really a book about music editing, no telling what Mueller makes of what Teo Macero did to the Columbia Miles Davis LPs. Awkard for the thesis that Miles gave Teo carte blanche (except for “Quiet Nights,” which Macero screwed up and Miles hated). The most heavily edited LP by Mr. White Capitalist Male, “Bitches Brew,” was Miles’ biggest hit among the black urban community.

Also, limiting the evolution of the LP to just jazz seems to distort the whole picture. What of Chess or Stax Records? That seems to go against the thesis pretty strongly here. Also, anything about the evolution of the LP both as a unique artistic medium and a commercially viable entity (especially among teen girls, who dominate the LP-buying demographic to this day) needs to include the Beatles.

Finally, I fail to see what gender would have to do with any of this, other than working with the gender imbalances in early jazz and the record business generally. But that isn’t either helped or hindered by the recording medium. But I haven’t read the book.

Allen-The book only goes to 1959, so some of what you say just doesn’t apply. He actually covers the combinations you mention-sets of 45’s and 10″ records-that’s part of what I meant by the book’s useful nuts and bolts. He doesn’t get into the Davis-Macero stuff, as I recall.

In terms of gender, as far as I know there is no book about jazz from an academic that doesn’t use it as a major filter in talking about anything. It’s certainly relevant to discuss the issue, but gender, like race, is used in such a determinitive way that the character and motivations of an individual are rendered insignificant. As far as I’m concerned, ignoring the difference between, say Herman Lubinsky and Michael Cuscuna, is not good writing of history.

Thanks, Steve. Good to know.

It’s impossible to separate the LP, or any physical recording medium for jazz, from how the vinyl is played. Seems to me there would have to be a parallel book about record players, jukeboxes, radio stations, and listening rooms: Where were they, who could afford them, how quickly were they adopted, how much were they available? How did any/all of this change as the technology got better (stereo, hi-fi, better cartridges, and the like)?

And, inevitably, the deterministic class/race/gender of it all.

The implementation of any format is extremely complex. The difficulty of pinning down details, such as those you mention, should make writers a little more reticent about making grand historical pronouncements. I think, at his point especially, that it’s too easy to let blanket evaluations on the basis of gender and race do that work for you.