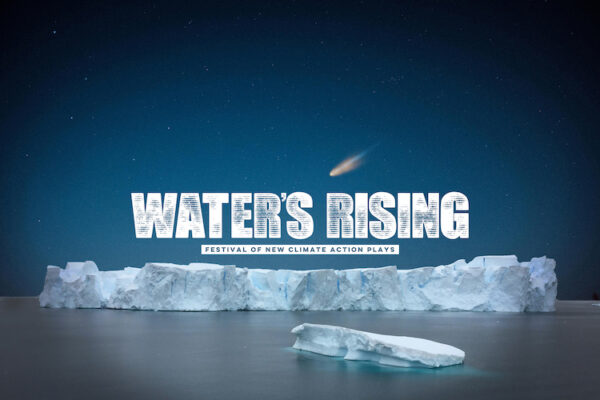

Theater Interview: GSC’s Rebecca Bradshaw on “Water’s Rising: Festival of New Climate Action Plays”

By Bill Marx

“We need hope in the possibility of change in order to survive what’s coming.”

I have been outspoken in my impatience with Boston-area theater’s lack of concern with an issue that many would argue is the overriding emergency of our time and time to come — the climate crisis. Our companies either ignore what seems (at least to New Englanders) to be a slow-moving global tragedy or treat it as a box to be checked off before moving on to more appealing (and boffo) topics. In 2022, the American Repertory Theater presented the non-Broadway bound climate allegory Ocean Filibuster, which freed it up to return to its usual lineup of commercially palatable New York fare.

The truth is, provocative scripts are being written about the degradation of the environment, the best often pitting conflicting perspectives against one another. But they aren’t being selected for production. As I wrote in a recent column, “theater should be part of a worldwide effort to alarm, inspire, and challenge. Our stages need to project speculative utopias and dystopias, look for ways to change hearts and minds, and encourage collective action by collaborating with concerned organizations and unions. The theatrical imagination should be tapped to map the way forward. That it is being left in the wings — aside from a workshop or two — is deeply troubling.”

So it is with real pleasure … bordering on existential relief … that I salute Gloucester Stage for its upcoming Water’s Rising: Festival of New Climate Action Plays (April 26 through 28 at 7 p.m. at Gloucester Stage, 267 East Main Street, Gloucester). The company vetted over 2oo submissions and selected three scripts for staged readings: Maximilian Gill’s A Few Fun Facts About Greenland on April 26; Hannah Vaughn’s Cincinnati by the Sea on April 27; and Emma Gibson’s If nobody does remarkable things on April 28. Each play will be followed by a talkback session featuring experts on the climate; they will address “the themes of the theatrical piece, highlight organizations taking action, and discuss the impact of climate change on Gloucester and the global landscape.” May this event inspire other companies to follow suit with full productions of dramas that deal with climatic disruption. Not only are the oceans rising — they are warming up to dangerous levels.

I emailed a few questions to Gloucester Stage artistic director Rebecca Bradshaw about the festival, how scripts can find the right dramatic balance, and the reluctance of theater companies to deal with the climate crisis.

Arts Fuse: Playwright Chantal Bilodeau has said that the climate crisis has been called a “crisis of imagination. The phrase refers to our inability to grasp the magnitude and violence of the changes we are facing, our reluctance to let the reality of it permeate our collective consciousness, and our resistance to envision positive futures.” Would you agree?

GSC artistic director Rebecca Bradshaw. Photo: Darcy Rose

Rebecca Bradshaw: Yes, I would. I believe theater has the power to unpack extreme realities and the future of our planet is in extreme crisis. We need to no longer ignore it. We need to work within our communities to adapt and change because we can no longer stop climate change. Theater is an art form that can change minds through storytelling. It’s harder for me to be changed by a scientific study, but if I see someone who I can relate to going through a hardship that sits with me emotionally, then when I am outside of the theater walls, I am reminded of that resolution when confronted with a similar dilemma. Theater may not save lives, but we can save a few souls along the way.

AF: I would add that it is also a crisis in terms of taking chances in programming. Many theater companies in the Boston-area and beyond are afraid to stage plays that deal with the climate crisis. It is felt that scripts on the topic will inevitably depress audiences. You obviously don’t agree …

Bradshaw: Believe me, I have many days that it is much easier to curl up and not think about the magnitude of the world’s problems. But I believe there is a power in putting a story on stage and saying “look, this is important.” The climate crisis affects everyone. The floods won’t care what political party you back when they continue to break down our seawalls. Theater is a powerful medium to unpack complex and hard realities TOGETHER across all lines. I also learned a ton from reading these plays. It made me google things I didn’t know about. By learning more about the world and its future, you become a better citizen, a better neighbor. And I think you will find out that the plays selected for this series leave you in a more hopeful place than expected because at the end of the day, we need hope in the possibility of change in order to survive what’s coming.

AF: Do you see a generational divide in theatrical responses to the climate crisis? I find that younger performers and writers are much more concerned with creating a theater that moves away from nostalgia and grapples with the future.

Bradshaw: In general, sure. There is an inevitable fighting rebelliousness in a younger generation that may become jaded with age. However, I’ve been at climate marches with folks double my age yelling as loud as me. I have also been in too many lobbies to know that one critical dismissive thought will be refuted with celebratory gratitude by another — often in the same audience! Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. I think the key is balance. Balance within a season, balance within a performance. This is why I look for plays that showcase a moment of deep cathartic humanity. We may not have had experience in our lifetimes yet, but that doesn’t mean we won’t in our future.

AF: You had over 200 submissions to Water’s Rising. So dramatists are interested in writing about what is happening to the climate. What were the strengths and weaknesses of the plays that were submitted? Were there any surprises?

Bradshaw: For some reason, I was nervous that we would receive a bunch of heady scientific plays that read more like research studies. However, what we received was a ton of plays about humans from all walks of life dealing with the emotional and factual change of the world around them. Of course, there were allegorical plays set in metaphor, but more and more the climate issues addressed were concrete and issues facing a specific community. It made me realize how many examples we have of witnessing climate change in our day-to-day lives.

AF: Do you see “climate action” dramas as inevitably political? What other kind of “action” are we talking about? Doesn’t that approach cut against the apolitical grain of American theater?

Bradshaw: Theater is political. Whether you agree or not, as a producer I am putting things that I and our company think are important onstage and telling everyone to witness them. The climate around us has been changing for decades, if not centuries. The earthquakes don’t care if you voted for Trump. Climate action plays should be the most bipartisan theater we produce. Emphasis on should.

AF: What do you think should be a theater company’s commitment to the climate crisis? It seems to me troupes should move with alacrity. It was not reported much in American media, but in an April 10 speech UN Climate Change executive secretary Simon Stiell posited that we have about “two years to save the world.”

Bradshaw: Oh, I would love it if everyone put on a play that had themes of the world’s climate crisis. More informed thinkers about this issue will breed more change. We cannot turn our back on the world changing daily around us. The reality of “two years” is terrifying, but I have been thinking about the planet since I learned the importance of cleaning up our green spaces in Girl Scouts as a kid. I have been trying to leave any space better than I found it and it maddens me that others do not. Humans caused this, so we have a responsibility to not make it any worse. It’s a fight. Fights are hard and uncomfortable. But adapting to what is happening is the only way to mitigate the damage.

Bill Marx is the editor-in-chief of the Arts Fuse. For four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: Climate Change, Climate Crisis, global warming, Gloucester Stage Company, Rebecca Bradshaw