Jazz Album Reviews: New Sets of Previously Unreleased Music — Art Tatum, Yusef Lateef, and Others

By Steve Elman

These four sets among five new collections of previously-unreleased music provide crisp snapshots of renowned jazz performers in the second half of the twentieth century and precious documents of great originals in their prime.

Art Tatum: Jewels in the Treasure Box [1953]; Yusef Lateef: Atlantis Lullaby: The Concert from Avignon [1972]; Sun Ra: At the Showcase – Live in Chicago 1976 – 1977; Mal Waldron & Steve Lacy: The Mighty Warriors [1995]

The passage of time often changes one’s perspective. As artists die, their undiscovered work takes on a sheen it might not have if it had come to the market in its time. Five new sets of previously unreleased music prove this once again, providing crisp snapshots of renowned jazz performers – in Chicago in 1953; in Avignon, France and Tustin, California in 1972; in Chicago again in the mid-1970s; and in Antwerp, Belgium in 1995.

Depending on your perspective, you will probably find one of these releases invaluable. But your sense of their importance will depend directly on what kind of music you value.

Chet Baker & Jack Sheldon: In Perfect Harmony – The Lost Album [1972] (Jazz Detective / Elemental) is a genial outing for two trumpeter-singers, a West Coast pairing with a section that includes pianist Dave Frishberg. Sun Ra: At the Showcase – Live in Chicago 1976 – 1977 (Jazz Detective / Elemental) captures the last territory band on its home turf with ample space for saxophonist John Gilmore, a circus of music that was the Greatest Show in Jazz. Mal Waldron & Steve Lacy: The Mighty Warriors [1995] (Elemental) represents one of the most focused and passionate performances so far released by two unique talents, with extraordinary support from rhythm players of the first rank.

Two other Fuse writers have already weighed in on these recordings. Steve Provizer opined on Baker – Sheldon (and provided a compare-and-contrast feature about the same artists in 2019) and Michael Ullman provided perspective on the Sun Ra set.

I am batting cleanup on the other three, and I have some additional comments below on Sun Ra.

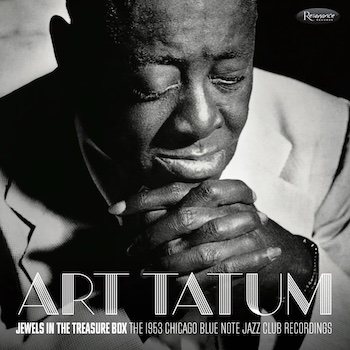

Photo: Herman Leonard

Art Tatum: Jewels in the Treasure Box [1953] (Resonance) is the most extensive document yet discovered of club performances by one of the great masters, working with his regular band in a very sympathetic venue.

I will be forever grateful to my father for introducing me to Art Tatum. Ed Elman was an amateur accordionist and, like every other keyboard player in the world, he could not believe Tatum’s virtuosity and inventiveness. “And this man is blind!” he’d say, shaking his head, not knowing that Tatum had a tiny bit of visual ability – it was functional blindness, to be sure. I am also grateful to him for never once mentioning that Tatum was Black; I learned that fact only years after I had come to appreciate him.

But that fact (or the irrelevance of it) was an essential part of the Tatum legacy. The man’s ability at the piano was so dazzling that it eclipsed his racial identity. Vladimir Horowitz and Sergei Rachmaninoff were not afraid to go to jazz dives on 52nd Street to hear Tatum play; Tatum might never have been allowed to see them perform in some of the segregated venues of the US, but they knew an artist when they heard one.

Volumes have been written about the rhapsodic way Tatum interpreted tunes of the Great American Songbook, his thrilling speed, his absolute control of every tool in the pianist’s arsenal, the way he executed the most difficult passages with unerring accuracy . . . the superlatives make him sound superhuman.

I will not add to them, nor will I bother to highlight naysayers’ concerns that he used the same motifs in every performance of a particular tune, that he occasionally chose some very thin material as vehicles for his wizardry, that he seemed unconcerned with the original emotional content of the songs he was playing, that he was constrained by the presence of a rhythm section, and that sometimes his live performances seemed to lack passion or fire. Those are small snowballs thrown at a statue a hundred feet high.

Jewels in the Treasure Box is a 3-CD (or 3-LP) set that presents 34 performances by Tatum’s trio and five solos, all recorded at the Blue Note in Chicago over a period of 14 days in August 1953. There is only one song duplicated – “There Will Never Be Another You,” which Tatum uses as the introduction to “September Song” on August 16 and as the introduction to “Judy” on August 21. Each of the trio performances is carefully worked out, with bassist Slam Stewart barely playing second fiddle to Tatum, taking every solo in his usual extrovert style, singing wordlessly along with his arco playing. Guitarist Everett Barksdale has only a few moments to shine, because Tatum doesn’t need an instrument to supply additional harmonies; even so, Barksdale’s strumming is a kind of substitute for drumming.

All of this shows how detail-oriented Tatum was. He had a choreography in mind for each of these performances, and his partners never deviate from those ideas. They all know where the tune is going and where the emphases will be. It does not mean that these renditions are formulaic, especially on tunes that are relatively rare in the Tatum discography – “I’ve Got the World on a String,” “Tabu,” “Judy,” “Dark Eyes,” “If,” “What Does It Take,” and “Air Mail Special.” The last three are particularly interesting – “If” for its intriguing chord structure, “What Does It Take” for its stop-time arrangement, and “Air Mail Special” for the freewheeling quality of the performance. Hearing a Tatum interpretation that is not familiar from other recordings of the same tune provides valuable insight into how any one of these performances would affect a listener hearing it for the first time – that is, how utterly astonishing the piano playing is.

A seasoned Tatum listener looks for nuances, little signs that the performance is being invested with special feeling. I hear these qualities especially in the final set here, from August 21. These tunes seem just a bit looser than the others, as if Tatum, Stewart, and Barksdale have really gotten comfortable in the venue and have a good crowd on hand – Tatum points to this in his closing remarks, where he says, “You’re a lovely audience, so nice and quiet. We love you dearly.” This contrasts with his gentle admonishment of the audience a week earlier before doing a solo on “Someone to Watch Over Me” (“If you’ll just be a little quiet, I mean, I’d appreciate it, ‘cause I’m going to play piano by myself, and I’m not going to play loud. Thank you.”)

Those who love Tatum and his other recordings do not need this new set, but there is enough worthwhile material here to give them plenty of new enjoyment. And if you are among the few who might say, “Art who?” the variety of the program will make this a worthwhile place for you to start your Tatum appreciation.

The sound quality is good, although not first-rate – there is some distortion in the original Frank Holzfeind recordings, and the restoration engineers have done as good a job as can be expected. (Holzfeind, the owner of the Blue Note, was using what the notes call “portable gear” for his archive recordings. He probably had a standard consumer tape machine of the early ’50s and the typical consumer mics of the day. Most amateurs weren’t springing for the cost of professional mics in those days.)

Still, the commitment of these trio performances is anything but perfunctory. They are perhaps the best example yet of an extended Tatum live stand at a single venue, proof of his amazing consistency and the precision he demanded of his sidemen.

Most writers are so impressed by Tatum’s technique that they never get beneath the surface of his work. But there is much beneath that surface. Tatum was an heir to the legacy of the great Romantic pianists. He had Liszt’s technique and Chopin’s delicacy, grafted onto a Harlem stride sensibility. Like the Romantics, he knew that his music had a functional role in society, and he knew that relatively few of his listeners were appreciating him as an artist. He always knew he was there to entertain, and he seems comfortable with that role.

But a Tatum aficionado lives for those moments when he reaches emotional peaks in his playing, where the music has an almost operatic intensity. I think this set has some of those peaks – on “Air Mail Special,” “If,” and especially on “Tea for Two” and “Lover” (where you can hear Barksdale working hard to stay as hot as Tatum).

Photo: Jan Persson

Yusef Lateef: Atlantis Lullaby – The Concert from Avignon [1972] (Elemental) is a superbly-recorded European date from a quartet of masterful players, serving as a reminder not only of the leader’s versatility but the brilliance of pianist Kenny Barron and as a timely memorial to drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath. The 2 CDs (or 2 LPs) are eminently satisfying.

Reedman Lateef (1920 – 2013) occupies a stylistic space between Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, and his music draws from hard bop, modal, and free-form bags. This set shows off all his facets – his big vocal sound on tenor sax, his use of Middle-Eastern and Indian modalities, his solid groove playing, his appealing tone on flute, his ability to stretch into free-ish territory, and his ventures into exotica (represented here by a duet with Lateef on Indian flute and Bob Cunningham on bass).

Bassist Cunningham (1934 – 2017) was ever a solid rhythm player, and he shows off his groove chops on “Yusef’s Mood,” a 17-minute boogie blues that puts the session in the alley. But he has some beautiful spots playing arco as well.

Albert “Tootie” Heath (1935 – 2024) was a compleat drummer. By this point in his career, he had adopted the African nickname “Kuumba,” and Lateef uses it several times in his intros and outros. His death on April 3 of this year makes the release of this set especially poignant and valuable. Every aspect of great jazz drumming can be heard here, and his responsiveness to each soloist (along with a lovely tune he wrote for the duo mentioned above) is a consistent delight.

Pianist Kenny Barron (born 1943; he’ll turn 81 in June) is all over this release and might even deserve credit as co-leader – he is the composer of three tunes, a strong soloist, and the glue that holds the section together. His reputation has only grown as he has achieved senior status in jazz, but this set shows that he was a fully-accomplished artist at 29. He plays straight when called for (beautifully on his own “A Flower,” a duet with Lateef on flute that is one of the highlights of the album), funkily (in an extended solo on “Yusef’s Mood”) and near-out (on his own “The Untitled”).

Pianist Kenny Barron, who is almost a co-leader with Yusef Lateef on Atlantis Lullaby. Photo: courtesy of the artist

The sound is superb. This was is a recording made for RTF (Radio-Télévision Française), and like so many other jazz recordings made by European broadcast institutions, it is as meticulous in its detail as that of any recording of a classical ensemble.

Overall, the rapport is rich – including the band’s good-natured vocal backup on “Yusef’s Mood” – and the vibes are right. If you do not own any other Lateef recordings, this one would represent his work very well for your collection.

The cover of Sun Ra Live at Montreux, a recording made the year before At the Showcase – Live in Chicago 1976 – 1977. Photo: Ken Haas.

Michael Ullman’s comments on Sun Ra: At the Showcase – Live in Chicago 1976 – 1977 (see above for a link to his review) offer wise perspective on a very valuable release. I’ll just add these notes.

Sun Ra’s career was based on a persona and a metaphor. He wanted to make music on his own terms, and if it took the manufacture of an elaborate circus of trappings to get people to lay their money down, he accepted that idea, embraced it, ran with it, and made it into something never before heard in jazz. It was Music for the Space Age, even if the nature of Ra’s Space Age was a fantasy of Africaphilia, Dollar-Store costumes, fire-eaters, free improvisation, acrobats, cheesy electronic keyboards, hand-made headdresses, and an occasional look back to his roots as a pianist with Fletcher Henderson as the Swing Era was drawing to a close.

Throughout his performance life, Ra always was a kind of Janus figure, looking in two directions at once. His earliest recordings have a lot of straight-ahead post-bop material amid the space music, and two of the compositions in the 1977 concert released here – “Velvet” and “Ankhnaton” – revive early works. That show also has a cover of Art Hickman’s hoary “Rose Room,” which was previously released on a set called Hendersonia: Sun Ra Performs Fletcher Henderson. This is not one of Ra’s re-creations, like his reboot of Henderson’s “Yeah Man” (represented by several versions on other Ra recordings) where John Gilmore faithfully reproduces both the clarinet solo (by Russell Procope) and the tenor sax solo (by Coleman Hawkins) from the 1933 original. In this take on “Rose Room,” Gilmore is given the floor to do what he wants to, and he roars through it, quoting “Love in Bloom” and “Salt Peanuts” along the way in a very good-humored vein.

The other concert here has a lot more of Gilmore, the crowd-pleaser “Space is the Place,” and one of the most unusual pieces in Ra’s discography, where trumpeter Akh Tal Ebah begins speaking in tongues and then slides into scat.

Like Michael Ullman, I remember Ra in performance, and this set brings me back. When you went to see Sun Ra in the ’70s, you were part of what used to be called a Happening, but you never knew what would happen. The band might play it straight, or play out, or march into the audience singing, or serve as the backup band for vocalist June Tyson. You only knew that Ra would be a magisterial presence, that he would play outrageously and brilliantly on his organ and synthesizer, and that the band somehow knew what he wanted them to do as if they were wired into a collective consciousness in another dimension.

Of all five of these fine releases, I have the greatest regard for The Mighty Warriors.

Pianist Mal Waldron and soprano saxophonist Steve Lacy were firmly rooted, even though both had identities that might be considered “avant-garde.” Anyone who takes the time to listen to their work with both ears will hear artists who know and understand the great traditions of jazz, and he or she will hear them working to extend those traditions into personal languages of great force and elegance. When they played together, the meeting of their minds was usually illuminating and occasionally transcendent. The latter kind of encounter is preserved on The Mighty Warriors, a Belgian concert in 1995, when both Waldron and Lacy were at artistic peaks.

Photo: Kanji Nakayama.

The set is really a Waldron trio set with Lacy as guest artist, although the “supporting players” are true giants themselves, with their own articulate reminiscences captured by producer Zev Feldman for the liner notes.

Bassist Reggie Workman has an awe-inspiring career, and his ability to do anything on his instrument makes him perfect for this ensemble. His gorgeous sound has rarely been captured so richly; so few jazz bassists have proper intonation on arco, much less an individual sound when using the bow, but Workman has both. His pizzicato playing is (of course) impeccable. His compositional contribution to this date, “Variations on III,” is a deep-focus contrast to the other repertoire (tunes by Monk, Waldron, and Lacy), and the other players give full attention to his ideas, which range from duet sections to free-form improvs to a Workman arco solo and a hint of a written line, stated at the very end.

Andrew Cyrille is a revelation in this release. He is known mostly for his extraordinary avant-garde work with a who’s who of innovative players. Even so, he could play straight time very effectively, as he did in 1982 in an album with Ted Daniel and Sonelius Smith (The Navigator, Soul Note). This 1995 session shows how versatile he is in-tempo, with solos that show a sense of melody on drums that is akin to Max Roach’s.

Steve Lacy always was himself, a master of every nuance of the soprano saxophone, and a soloist of economy and wit. Here, to a certain extent, he takes his cues from Waldron; still, he is in superb form. He contributes one of his obsessive tunes, “Longing,” to which the other players give a lovely rolling spring; the obsession never seems tense. Cyrille approaches it as Elvin Jones might have, well behind the beat, which is a departure from the approach the drummers take in many of Lacy’s own recordings.

Waldron is so strong a pianist that he is like a full orchestra behind the other players. His signature pedal points are on ample display here, in his originals, “What It Is” and “Snake Out.”

In “What It Is,” everyone works within and against a strong tonal framework – no one seems constrained by it, and the performance has a lot of power as a result.

“Snake Out” is one of this album’s highlights. The line is a series of repeated arpeggios contrasted with pedal-point chords. This tune has Lacy’s most active solo of the night, but there is melody anchoring all the effects he calls on. Workman has a fine pizzicato solo with delicate Cyrille accents under him, fleet and very smart. Cyrille’s own solo has lots of open space, with fingers on toms, careful use of cymbals, rumbling rolls, and some tap-dancing on the rims. Waldron’s solo, without the other three, is built on a Cecil Taylor line (at least per the title on the jacket), but I’m inclined to think that this is one of Mal’s little jokes; it’s the most melodic CT line I’ve ever heard, with some very familiar chord changes. The pianist ends his statement with tremolo emphases of those familiar chords, and then re-establishes the pedal point of “Snake Out,” leading into the outchorus.

The other two tunes draw from the songbook of Thelonious Monk, a composer the co-leaders revere as a master and an inspiration. “Epistrophy” is a classic, of course, but the respect Waldron and Lacy have for Monk doesn’t get in the way of this being a sensational interpretation of the tune. “Monk’s Dream” is yet another gift, with a great Cyrille solo; his vocal interjection within it is so musical that it’s a legitimate element in itself.

This beautiful recording is not attributed to a particular studio or broadcast outlet, but I’m inclined to think that it comes from Belgische Radio- en Televisieomroep, the Belgian state’s Flemish broadcast service at that time. As with the Lateef date also issued this month, the engineers involved extended it tender loving care, and the mix is perfect. This is one of the rare “unreleased recordings” that sounds as good or better than anything previously on record from any of the four players’ discographies.

In 1995, Lacy was 61. Waldron was 70. Workman was 58 (he is now 86). Cyrille was 56 (he is now 84). It is precious to have this document, one of the best performances ever by Waldron and Lacy, together or separately, with two brilliant rhythm players providing outstanding support. It represents an ideal introduction to any of them.

More:

As with all Zev Feldman’s recent productions or co-productions, the package for each of these releases is a model that makes it a collector’s item – beautiful design, great photos, comprehensive notes. I expect to talk with Feldman soon and provide an appreciation of his work in a future post.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

Tagged: "At the Showcase – Live in Chicago 1976 - 1977", "Atlantis Lullaby – The Concert from Avignon", "Jewels in the Treasure Box", "The Mighty Warriors", Andrew Cyrille, Art Tatum, Mal-Waldron, Steve Lacy, Sun Ra, Sun Ra Arkestra