Music Commentary: A Deep Dive into The Mothers of Invention’s “Plastic People”

By Trevor Fairbrother

Frank Zappa’s tight editing ensured that “Plastic People” was a compelling aural creation, and his fierce confidence compelled listeners to pay attention to the words.

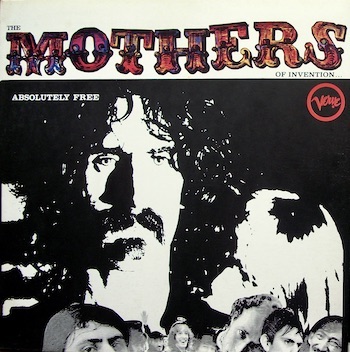

Absolutely Free was the second album by California’s inimitable nasty rock band, The Mothers of Invention. When it was released in 1967, I responded emotionally to the mutinous array of musical styles and weird humor, but in truth I was ignorant about the work’s origins and context. Today, a vast stockpile of internet data informs me about things previously beyond my reach. Online foraging has deepened my admiration for the album’s experimentalism and the brainpower of its composer, Frank Zappa (1940–1993). This essay takes a close look at “Plastic People,” the opening track.

Absolutely Free was the second album by California’s inimitable nasty rock band, The Mothers of Invention. When it was released in 1967, I responded emotionally to the mutinous array of musical styles and weird humor, but in truth I was ignorant about the work’s origins and context. Today, a vast stockpile of internet data informs me about things previously beyond my reach. Online foraging has deepened my admiration for the album’s experimentalism and the brainpower of its composer, Frank Zappa (1940–1993). This essay takes a close look at “Plastic People,” the opening track.

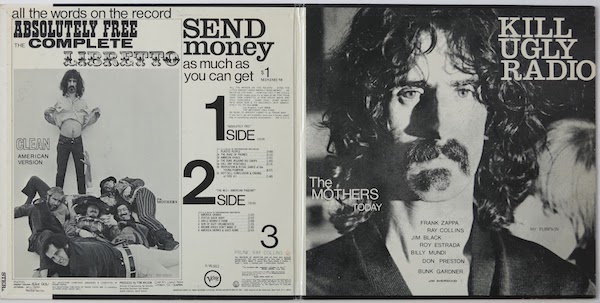

The Mothers recorded Absolutely Free in four sessions in Hollywood at T.T.G. Inc.; then the material was edited and remixed at MGM Studios in New York City. Those efforts took place over the course of two weeks in November 1966, and were unusually long and expensive for rock music at that time. Surprisingly, six months passed before Verve Records released the album. The group wanted a gatefold sleeve that included all the lyrics and the company balked at some of the language. The Mothers withstood censorship and Verve’s end product was a visually ebullient gatefold with no lyrics. Independently, the group made the “complete libretto” available by mail order. Accordingly, the sleeve included a prominent text that plugged the indie publication: fans were invited to send a minimum of $1 to receive a booklet with “all the words on the record … even the little sneaky ones.”

“Plastic People” begins with a drum roll and the formal introduction of the President of the United States. He says two words — “Fellow Americans” — then someone (the President?) intones “doot doot doot” to oafishly plunked guitar sounds. “He’s been sick,” someone explains. This is the first of several sections devoted to recordings of men talking, with weird musical fragments in the background. Next comes the chorus: “Plastic People, oh baby, now you’re such a drag.” This stern pronouncement lasts about seven seconds. The third structural element is the verse: an infectious and delectable mid-tempo R & B item. Zappa uses these elements multiple times, relying on an abstract sensibility to make patterns and set up sonic disjunctions. He incorporates an instrumental break and closes his composition by riffing out the third R & B unit while spoken comments, some in Spanish, swarm to a crescendo.

Zappa’s tight editing ensured that “Plastic People” was a compelling aural creation, and his fierce confidence compelled listeners to pay attention to the words. The surreal scenarios included a “guy from the CIA” who creeps around Laurel Canyon and “a vast quantity of plastic people” marching on Sunset Boulevard to Pandora’s Box. The commentary ranged from political pragmatism (“It’s hard to defend an unpopular policy”) to rueful lovers’ banter (“Sometimes I just get tired of you, honey, … it’s your hairspray or something”). Zappa deftly inserted the R & B hook to keep everything aflutter, while keeping the lyrics consistently chaotic and absurd. One verse described sappy devotion to a woman who “paints her face with plastic goo,” and another encouraged listeners to confront bigotry and conformity: “Take a day and walk around / Watch the Nazis run your town / Then go home and check yourself / You think we’re singing ’bout someone else.”

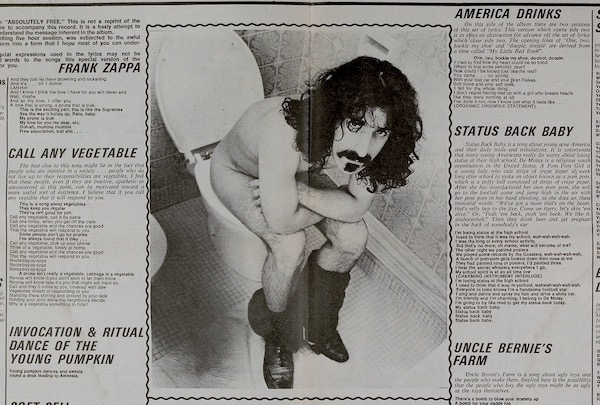

Absolutely Free: open gatefold of the American sleeve.

Tom Wilson, the prescient African American who had recently produced Bob Dylan’s revolutionary recordings with rock musicians, signed The Mothers to MGM/Verve in early 1966. Freak Out!, their debut album, was released in the US in June that year. The band presumed the freedom to veer in any musical direction — from orchestral soundscapes, experimental and electronic genres, jazz and R & B, to Doo-wop — and they crafted literary/musical social satires which they directed at anything and anyone, including themselves. In fact, Freak Out! heralded the start of their war on plastic. The song “You’re Probably Wondering Why I’m Here …” included these lines about fashion-crazed young adults who didn’t know how to (or didn’t want to) think for themselves: “You boogied all night in a cheesy bar / Plastic boots and plastic hat / And you think you know where it’s at?”

I was a low-born English teenager in a semi-industrial wasteland when I fell for Absolutely Free. Evidently, the buzz about the group in the weekly pop music tabloids reached me, but I don’t remember any breakthrough moments. My passion for music had been guided by the amazing trajectory of the Beatles, from peppy hit parade exuberance (“From Me to You,” April 1963) to dense psychedelic experimentalism (“Strawberry Fields Forever,” February 1967). I probably saw The Mothers as exotic foreigners who were harbingers of aspiration. For parochial me, London was another country, and Los Angeles another planet. How could I understand their comments about Pandora’s Box? Twenty-first-century folk can easily learn that it was a club on the corner of Sunset and Crescent favored by trendy juveniles. Moreover, the month before The Mothers recorded Absolutely Free local officials enforced a curfew to mitigate the crowds and traffic jams, leading to protest rallies and conflicts between the cops and the kids.

My strongest association with the opening song was the titular plastic. I grew up in an English working-class culture pelted with such plastic products as artificial flowers, hula hoops, and industrially processed milk. I remember the advent of vending machines dispensing saggy pyramidal plastic bags filled with milk. The opening sequence of the 1964 movie A Hard Day’s Night spoofed the phenomenon: the Beatles’ road manager makes a purchase on the platform of a train station, then struggles to tear through the plastic with his teeth. Another connection for me was The Who’s 1966 single “Substitute.” Pete Townsend may have intended the protagonist of that song to remain enigmatic, but he was overt, nonetheless, in equating the word plastic with British social and economic hierarchies that subjugate the working poor. Hence the cherubic sarcasm of one crucial line (“I was born with a plastic spoon in my mouth”) and the glowering hurt of another (“I can see right through your plastic mac”).

Absolutely Free: back cover of American album.

Verve released Absolutely Free in the UK in October 1967. The tracks were the same but the visual and verbal hoopla was scaled back because the LP came in a standard (nongatefold) cover. Two key parcels of text were retained: an aphorism by Zappa’s avant-garde idol (“The present-day composer refuses to die!” / EDGAR [sic] VARESE, July 1921) and headings to indicate the album presented two suites or “Underground Oratorios.” Thus, on the first side, “Plastic People” introduced the seven-part cycle titled Absolutely Free, and the second side presented the six-part oratorio The M.O.I American Pageant. The one novel addition to the British sleeve was an untitled free verse commissioned from Mike Raven (real name Churton Fairman). Raven, a well-bred jack of all trades, hosted a blues show on the new “pop” channel BBC Radio 1. His overripe text (“the empty cesspits of our souls”) ended with these lines: “the voice is here for those with ears to hear / the plastic people will hear nothing but noise.”

Back then I was clueless about one exceptional musical feature of “Plastic People.” Being unfamiliar with the R & B standard, “Louie Louie,” written and recorded by Richard Berry in 1957, I failed to register that Zappa’s verses repeated its catchy chords and phrasing. In addition, he rehashed some of the lyrics. This is by Berry:

“Me see Jamaica moon above / It won’t be long, me see me love / Me take her in my arms and then / I tell her I never leave again.”

And here is Zappa:

“Me see a neon moon above / I searched for years and found no love / I’m sure that love will never be / A product of plasticity.”

Furthermore, the “doot doot doot” moment noted earlier bastardized the instrumental beginning of Berry’s song. Last but not least, Zappa’s chorus – “Plastic People, oh baby, you’re such a drag” – was a choppy makeover of Berry’s genial declaration “Louie, Louie, me gotta go.”

Years later I learned that Zappa occasionally explained the connections between “Louie Louie” and “Plastic People” on stage. In 1988 he released a recording of one such performance on You Can’t Do That on Stage Anymore, Volume 1. It was part of a 1969 show in the Bronx, New York, and it also featured a new verse: “Three nights and days I walked the streets / This town is full of plastic creeps / Their shoes are brown to match their suits / They got no balls, they got no roots.”

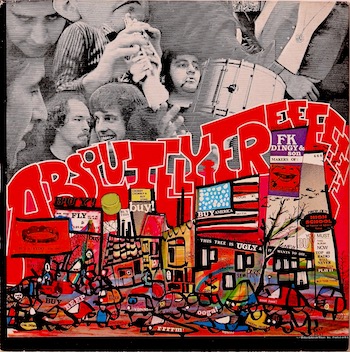

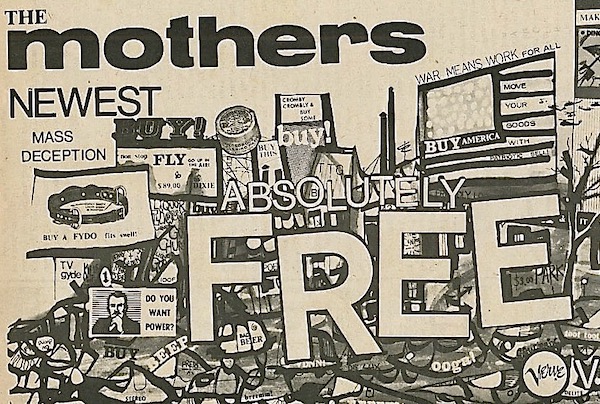

The standard format sleeve of the British Absolutely Free deprived consumers of most of the ebullient visual ingredients on the American gatefold. One key omission was the cartoonlike cityscape on the back. The US liner notes included the credit line “Cover Art, Layout, Notes, Collages, Etc. / ZAPPA,” implying that Zappa created that fiendish image. I thought more about this after enjoying the sections in Alex Winter’s 2020 documentary biopic that discussed Zappa’s day jobs in the early ’60s. During his brief first marriage he worked at the Nile Running Greeting Card Studio, in Claremont, 40 miles west of Hollywood. Although his main responsibilities were in production, he designed and promoted his own line of humorous cards targeting the younger crowd. The wacky red cityscape doubtless benefited from his experiences as a graphic artist, and I think he took inspiration from illustrator Geoffrey Dickinson, whose magazine covers included “LONDON: The Swinging City” (Time April 15, 1966) and an impressive run for England’s Punch. Zappa’s urban landscape may include Pandora’s Box and its tiled roof, dwarfed by billboards. There’s a giant Dadaistic ad for dog collars that shouts “BUY A FYDO – fits swell!” I see this congested picture as a visual correlative of “Plastic People.” Verve used a black-and-white version of the cityscape to promote the album in some American publications; those ads included slogans that did not appear on the album cover: “WAR MEANS WORK FOR ALL” and “MASS DECEPTION.”

Detail of ad for The Mothers in Hit Parader, September 1967.

My understanding of Zappa’s advanced dovetailing of art and business grew when I recently read (for the first time) press coverage of Absolutely Free from 1967. Zappa knew how to work the system in order to get a foot in the door, then build the niche in which he could create and try to sell his one-off music. His efforts to promote The Mothers, their new album, and their first concert in London (Royal Albert Hall, September 23, 1967) exemplified his ingenuity. One goal was to beguile London’s countercultural publication, International Times. Sure enough, on August 31, 1967, the paper lavished a suite of articles on the band, including the libretto of Absolutely Free annotated with comments to explain “the message inherent in the album” to the locals. (Zappa’s tidbit about the first track said, “The insincere ass holes who run almost everybody’s country are plastic people.”) There was also a full-page promotion for the new album and single: the layout was a solid black page and a skinny white slogan near the top: “we can’t afford to print the lyrics … / … but we can afford to buy an ad. / M.G.M. RECORDS.” The band was pretending to ridicule the company, while deploying an inverted badass stance that would entertain the young audience they wanted to reach.

International Times‘s centerfold presentation of the libretto included a nude photograph of Zappa maestro sitting on a toilet. 19-year-old Robert Davidson had snapped a dozen bathroom shots during a press event in the maestro’s London hotel room. His images spawned several posters, often sold by hip boutiques; there is an example in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Ironically, British copyright law prevented Zappa from controlling and benefiting from that little goldmine. Although he received no royalties, the posters cranked up his twisted fame.

An unsigned review of Absolutely Free in the London weekly Disc and Music Echo (September 2, 1967) exuded an air of triumph. After declaring The Mothers “the best American group,” it listed British rockers Eric Clapton, Eric Burdon, and Spencer Davis as key “Mother-lovers.” The album was deemed “equal in progression, wealth of ideas and solid musicianship” to the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper, and, at the same time, “much, much freakier and weirder.” After The Mothers left the UK Tony Palmer, a Cambridge-educated filmmaker, wrote a high-handed testimonial in The Observer, a liberal Sunday newspaper (October 22, 1967). He made the preposterous claim that their recent visit “was almost ignored” and their “assault on our own precious musical culture … passed by without so much as a ripple.” Palmer preened himself as he chided “Britain” for failing to appreciate the group’s derisive attitude towards “the whole self-indulgent shambles that people pretend is ‘popular culture.'”

Detail of centerfold spread in International Times, August 31, 1967.

Zappa had in fact been forthcoming and informative in meetings with the press. The American public, he argued, was enthralled and conditioned by manufacturers’ products, and blindly accepted all they were offered. Likewise, he saw the Flower Power movement as another phony product, generated by “the hippie machine.” He believed that he and his band members had created their own market, from the ground up: they alone had convinced people to support The Mothers of Invention.

These are excerpts from his conversation with Nick Jones, reporter for Melody Maker (August 26, 1967): “We seem to thrive in areas where there is unrest between the generations, because we tend to pep things up! … My theory is that in America they purposely avoid teaching you to evaluate for the reason that they don’t want everybody evaluating every piece of the world they live in…. The system is f[ucked]. It’s crumbling. But only the young can see this. The old people don’t see the muck they have caused and are wallowing about in. Their egos won’t allow it.” Zappa told reporter Hugh Nolan the group had sold over 250,000 records in America, even though they were completely ignored by radio stations (Disc and Music Echo, September 30, 1967). Undeterred and sharp-witted as ever, he confessed to a higher mission: “Selling records is a by-product of what we’re doing. We’re there to help out — sort of like singing social workers.”

It’s impossible to parse Zappa’s intentions when he communicated these ideals and criticisms in 1967. Nonetheless, history has confirmed these actualities: he remained outspoken on certain political issues, especially freedom of expression; his penchant for satire and theatricality diversified and coarsened in keeping with culture at large; his creativity as a guitarist and orchestral composer grew splendidly; and, ever the workaholic in the niche of his own creation, he was a prosperous purveyor of records and CDs.

Trevor Fairbrother is a writer and curator. If you liked this essay, check out “Vapor Trail,” a kindred item he wrote about Andy Warhol.

Tagged: "Absolutely Free", "Plastic People", Frank-Zappa