Traveling Exhibit Review: “Auschwitz — Not Long Ago. Not Far Away.”

By Robert Israel

Auschwitz: Not Long Ago. Not Far Away. is compelling, but its message feels hermetically sealed — the exhibit needs to draw crucial connections with what is going on now.

Yellow badge bearing the-word Jood (Jew), issued to Jenny Hanf. Photo: Musealia

Does the traveling exhibit Auschwitz: Not Long Ago. Not Far Away., now on view at The Saunders Castle at 130 Columbus Ave., across from Park Plaza in Boston, deliver on the promises implied in its title? Does it make viewers go beyond its startling images and think seriously about what led up to the creation of a Holocaust death camp? Does it challenge us to reflect on how this horrific chapter of the 20th century shapes our lives today? And one more question: does this exhibition force us to consider how the hard-earned lessons of the Second World War impact our world now — specifically in Boston, one of 14 cities on the show’s roving schedule?

For me, the answers to these questions are mixed. Yes, the exhibit is brilliantly staged and the staff of Musealia, a Spanish-based company that is responsible for mounting the show, deserves high praise. But the experience on display faltered because it did not forcefully connect the lessons of the Holocaust to the resurgent conflagrations of antisemitism that inflame our daily lives.

The exhibit unfolds along dark corridors with graphic images of life before, during, and after the Holocaust. The visual narrative traces the roots of antisemitism, exploring how — slowly and methodically — the Nazi rise to power nurtured a systematic process in which those deemed unworthy of Aryan value — namely Jews, Gypsies, homosexuals, and others — were singled out as less than human and marked as expendable. Mug shots taken by the Politische Abteilung (Political Department) line one wall. Like mug shots of suspected criminals today, this process set into motion a mechanized process that inevitably led to their ultimate imprisonment and extermination.

The prose explaining each step is terse and succinct, leaving no room for doubt. This was how methodically the Nazis worked, adhering to a systematic approach to identifying, persecuting, corralling, and then eliminating perceived enemies of the Reich.

In the exhibition: a woman’s dress shoe belonging to a deportee. Photo: Musealia

What makes this exhibit particularly compelling is its focus on the whole of the Holocaust and the sum of its parts. We see large photos of so-called “round-ups” of Jews and others, the stripping of their citizenship, the looting of their personal items, and their eventual transportation to the death camps. No Jewish population escaped their purview: Jews, arrested from as far away as Ioannina, Greece, were sent to be murdered in Auschwitz. There is, in a small display case, a small red dress shoe worn by a woman. It was found among the thousands upon thousands of shoes taken from Auschwitz’s prisoners. That one small shoe reminded me of the image of a girl in a red coat in Steven Spielberg’s movie Schindler’s List. The image speaks volumes about the losses that occurred.

But what troubled me was the lack of connection to Boston, in particular, and to the rise in antisemitism in these United States, and, indeed, the world, especially in the wake of the Hamas massacre of innocent Jews in Israel in October 2023.

I asked Luis Ferreiro, director and CEO of Musealia, why a stronger statement was not being made that conjoined these links.

“The aim of the exhibit,” Ferreiro told me, “is to show how societies make small steps leading to this kind of terror, and that we all need to understand that the Holocaust brought engineers, doctors, and many others together to plan it and to operate it. It is being aimed at educating those in the 21st century that the responsibilities lie within each of us to prevent such human tragedies from occurring.”

A Zyklon B gas can. Collection of the Auschwitz Birkenau State Museum. Photo: Pawel-Sawicki Auschwitz-Birkenau-State-Museum/ Musealia.

And what of the New England Holocaust Memorial, erected in 1995, which abuts the Freedom Trail across from Blackstone Block on Union Street? Or the plan to build a Holocaust museum on Tremont Street? Surely it is the exhibit’s responsibility to at least inform those visiting — many of them new to Boston — that we are aware of our history and are taking a stand.

And to that, I would add that a mandatory request be made for viewing a small statue, hidden by the side entrance of the State House on Beacon Street: a shadowy, less pride-worthy monument to Boston’s history, the oft-ignored bronze statue of Mary Dyer. Dyer and several of her brethren were hanged in Boston in 1660. Their crime? They were Quakers. On my way to Park Plaza, I walked past the spot where the Quaker lynchings took place on Boston Common. The passage of years from 1660 to 1940-45 indeed seemed “not long ago.” Puritan henchmen built public gallows to do away with Quakers in Boston; Nazi henchmen built the killing factories and murdered Jews in Oswiecim, Poland. In Boston, five innocent people were lynched; in Poland, the number of blameless Jewish men, women, and children who met their deaths — by hanging, asphyxiation, torture, starvation, and exhaustion — exceeded one million.

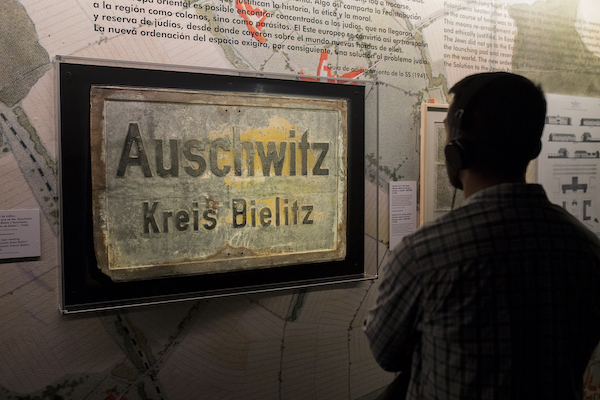

In the exhibition: A sign from Auschwitz. Photo: Musealia

But the exhibit does not provide these crucial details that connect its purpose to the very city that is hosting it. The least the organizers could to is to provide a detailed map of the aforementioned statue and Memorial, and to include additional resources directing visitors to where they might learn more about Boston’s role in WWII, about antisemitism here and in the United States, and how this exhibit links up to them.

The need to connect the past with the present is obvious. Two weeks ago, a Jewish student at SUNY Binghamton said she received online insults. Among them, “We tried our best to put you in Auschwitz” and “History will judge Hitler as a hero” were among the taunts she heard as she defended Israel’s existence on campus. Last week there was the plea of Jewish director Jonathan Glazer, whose film The Zone of Interest had just won the Academy Award for best international film. The movie presents images of the death camp as seen from the perspective of the Nazis; it is a harrowing study in cold-blooded indifference to inhumanity. Glazer bravely told the Academy Award audience when he accepted the award, “All our choices were made to reflect and confront us in the present — not to say, ‘Look what they did then,’ rather, ‘Look what we do now.’ Our film shows where dehumanization leads at its worst. It shaped all of our past and present.”

Auschwitz: Not Long Ago. Not Far Away. is compelling, but its message feels hermetically sealed — it needs to draw crucial connections with what is going on now.

Robert Israel, an Arts Fuse contributor since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Following up on Zone of Interest director Jonathan Glazer’s stingingly salient point about the relevance of “dehumanization,” one of the best books I have read on that topic is Making Monsters: The Uncanny Power of Dehumanization (Harvard University Press). I interviewed the study’s author, David Livingstone Smith here. One of his responses that has stuck with me:

Perhaps the “crucial connections with what is going on now” are not missing, as the author of this article suggests, but are painstakingly implied.

Anyone walking through the exhibition will surely find modern-day parallels without the curators detracting from the Auschwitz story being told and the honoring of its victims. The exhibition’s title does this brilliantly. As does the short film at the very end of the exhibition, which shows the normal life of happy, naïve pre-WWII families in Austria, Poland, the Netherlands, Croatia, and Czechoslovakia and cleverly juxtaposes the red shoe on display at the exhibition’s entrance. I had no problem making the connection.

Also: “Hatred, racism, antisemitism and intolerance are, unfortunately, concepts we still have to face nowadays,” said “Auschwitz: Not Long Ago. Not Far Away.” exhibition director Luis Ferreiro in a recent interview in The Times of Israel. “Therefore, it is of vital importance to remember the road that led to Auschwitz and the consequences it had.” Yup.

I have not seen the exhibit, but it must be pointed out that there are some concepts that resonate with the Holocaust that Luis Ferreiro didn’t go into in The Times of Israel feature.

Mass killing, for one. There are a number of genocides going on at the moment. Russia’s demolition of Ukraine and its people; the starvation and esculating murder in Sudan about which the West is “unforgivably silent“; and yes, Israel’s mass killings of the Palestinians. According to the U.N., more children have been killed in Gaza in recent months than in four years of conflict worldwide: “at least 12,300 youngsters have died in the enclave in the last four months, compared with 12,193 globally between 2019 and 2022.”

Would it be too much to ask that a Holocaust exhibit have a room that calls specific attention to contemporary instances of what many experts/historians would consider genocide? Even if it means disturbing viewers, perhaps even creating political controversy?

Other concepts that, unfortunately, we still have to face: indifference and collective madness.

Agree 100% with this. Visitors will easily find modern-day parallels in the descriptions of each artifact and each section of the exhibit as well as in the accompanying audio and videos with survivors. My mind immediately made the connection. The last 2 videos of the exhibit will resonate with me for the rest of my life. The exhibit is thought provoking and will put you on an emotional rollercoaster. It is all worth it because we need to be reminded of what evil and hatred can lead to. We must honor all those precious lives lost and those who survived by teaching future generations about the Holocaust and simply by never forgetting.

Of course, “we must honor all those precious lives lost and those who survived by teaching future generations about the Holocaust and simply by never forgetting.” Recent polls show that young people need to be educated about the horror of what happened. But I would add that we honor “precious lives lost” by doing what we can to save lives from mass killing today. A headline from two days ago: Sudan: 5 million at risk of starvation due to war, UN says. And of course, there is Israel’s wholesale destruction of Gaza.

From Naomi Klein’s fine piece in The Guardian on Zone of Interest — and the director’s statement at the Oscar Ceremony — about dehumanization:

In an exhibit I reviewed in Toronto on the (ongoing) conflict in Syria (https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/a-heartwarming-and-heartbreaking-exhibit/), the curators devoted a section to viewers’ responses, encouraging them to write/video their reactions to the exhibit’s scenes of destruction. A similar area devoted to further engaging the audience would help this exhibit immensely. Lastly, a handout detailing additional resources (the N.E. Holocaust Memorial, etc.) would anchor viewers to our community so that those attending, if they so choose, might participate in ongoing discussions, and further learning opportunities.

It is not the job of a traveling exhibition on a specific, devastating time in history to also cover all the atrocities, racism, and bigotry taking place across the globe in modern day.

It is simply enough to have a dedicated space covering this atrocious incident in history and not also curate galleries for the evolving situations taking place in Israel/Gaza, Russia/Ukraine, and, as the author asks for………. Boston(?)

Auschwitz and the Holocaust can stand on their own. And frankly, it wouldn’t do the topic justice to try and create parallels for people to modern antisemitism and racism in Boston.

I attended the exhibit last weekend and overall, I think it was well presented and informative. After visiting the Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum in Poland, I guess my experience here could only pale in comparison. Some improvements that could be made, in my opinion: Almost all of the items on display had corresponding labels/explanations but I do recall looking at a few artifacts, videos and photographs and having absolutely no idea of what I was looking at! Also, some of the family photographs of victims and survivors were so small that they really didn’t even merit the display space they took up. Why in this age of advanced photography, they were not blown up to large size for easier viewing, is beyond me! They could have had the original photograph side by side with a larger image to se the faces and people. Finally, I recall looking at several exhibits with German captions and wondering why they couldn’t have been translated them into English.