Classical Music Concert Preview: Cappella Clausura to Perform Ethel Smyth’s Mass in D

By Aaron Keebaugh

Mass in D was Ethel Smyth’s first large-scale score and, according to Cappella Clausura conductor Amelia LeClair, the composition expressed her yearning for hope and redemption.

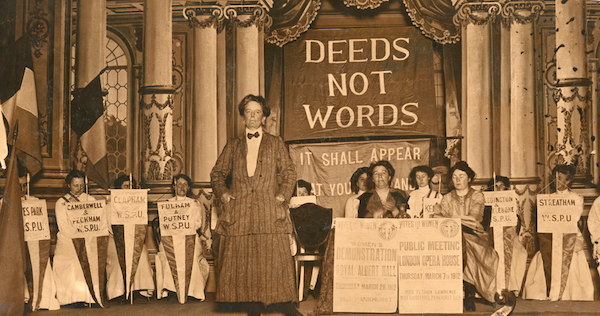

Ethel Smyth at a Women’s Social & Political Union (WSPU) meeting, 1912. Picture: The Women’s Library collection, LSE Library

By January 1891, Ethel Smyth had reached the lowest point of her life. Revelations of her love affair with the writer Harry Brewster, who was married, sparked a scandal, leading to her leaving Leipzig, where she was receiving her musical education, in 1885. Alongside that loss came the crushing break with Elisabet von Herzogenberg, Brewster’s sister-in-law, the wife of Smyth’s composition teacher Heinrich, and a close friend whom Smyth affectionately called “Lisl.”

Travels between her native England and Germany after that trauma only offered momentary solace. Alone in Munich one Christmas Eve, fighting illness, Smyth read The Imitation of Christ and experienced a revelation. “I had always thought of myself,” she recorded in her memoirs. “No wonder I had failed; no wonder all I had touched, no matter with what excellent intention, had turned to dust and ashes; no wonder that even Lisl was lost to me and that I had gone into the desert in vain. Now my path was clear.”

Smyth’s newfound religious fervor led to composing her Mass in D, which reflects the joys and sorrows of her life at the time. This was Smyth’s first large-scale score and, according to Cappella Clausura conductor Amelia LeClair, who will lead a performance of the piece tomorrow at Boston’s Emmanual Church, the composition expressed her yearning for hope and redemption. The rendition marks the score’s belated Boston premiere. Perhaps it will herald attempts to pay more attention to Smyth’s music, which may finally be getting its proper due.

That’s been a long time coming. While the past few years have witnessed a surge of interest in recording works by this distinctive British composer (and suffragette), Smyth’s music remains chronically underperformed in America. Cappella Clausura will be part of correcting that imbalance by performing LeClair’s edition of the Mass, scored for choir and full orchestra. This project has been long in the making: “This was in maybe 2014,” LeClair explained. ” [Musicologist] Liane Curtis introduced me to Mark Shapiro, who has the [notation software] Sibelius course in New York. And I had a conversation with him, and he said it would be a huge favor if [I] made an edition [of Smyth’s Mass in D]. At the time, I had never created an orchestral score.”

LeClair’s edition cleans up notational errors she found in a photocopy of the Mass from 1925. The new edition, she hopes, will enhance Smyth’s searching lyricism and culminating sweep.

LeClair’s edition cleans up notational errors she found in a photocopy of the Mass from 1925. The new edition, she hopes, will enhance Smyth’s searching lyricism and culminating sweep.

Completed in 1891, Smyth’s Mass in D eschews the traditional arrangement of Latin prayers in favor of a structure drawn from an old High Anglican practice. The Gloria is placed last; this way is delivers a sense of finality and hard-won triumph. Though Smyth would later in her career develop an affinity for the swirling mists of the Wagnerian style, she channels Beethoven in this score, with bold and urgent statements intermingling with passages of sumptuous melody.

“It establishes her as a composer of note,” said Dr. Amy Zigler, a scholar of Smyth’s life and music. “Here she is writing a large-scale work that is a litmus test for her life.”

Yet the Mass’s muscular tone and powerful tensions invited criticism at its 1893 premiere at Royal Albert Hall. Critic George Bernard Shaw wrote that Smyth composed “indiscriminately with the faith of a child and the orthodoxy of a lady.” Even when GBS grew to appreciate the piece when it was revived at the Birmingham Festival in 1924, he couched his praise in gendered terms. “You are totally and diametrically wrong in imagining that you have suffered from a prejudice against feminine music,” GBS noted in a letter to Smyth in March 1924. “Your music is more masculine than Handel’s.” Even a Grove’s Dictionary entry on Smyth from 1954 underlines that the Mass “placed the composer easily at the head of all those of her own sex” for its “virility and masterly workmanship.” Yet another review of the time calls her music “lyrical, ejaculatory, and dramatic.”

Though the 20th century gradually ate away at Victorian notions of a woman’s place in the arts, Zigler argues that “people were not expecting a woman composer and not expecting a woman composer to write like this.” There was always a caveat, even when her works were praised. “No matter what she wrote there was a lot of criticism,” Zigler added. “And if it was good, it was good for a woman.”

That damned-if-you-do, damned-if-you-don’t approach to women’s role in music no doubt contributed to how Smyth’s work was shunted to the sideline, even before her death in 1944. “History has found many creative ways of dismissing women composers,” music historian Leah Broad told VAN Magazine, “because they were too feminine, too masculine, too modest, too sensual, too famous, or not famous enough.”

Composer and suffragette Ethyl Smyth. Photo: Wiki Common

Still, Smyth was well known and much talked about in her day. Her work as both composer and suffragette earned her several honorary doctorates. The pinnacle of her achievement came in 1922, when she was named a Dame of the British Empire. Yet, as her music gradually faded from memory and performance, Smyth tended to be remembered for her eccentricities. She hunted, rode horses, and smoked cigars, which Zigler says were typically associated with masculinity. More recently, Smyth’s love affairs with women as well as men have defined her as a “lesbian composer.”

Looking at her music rather than her life discloses that she was a prominent voice in the musical world of Britain, then occupied by the likes of Hubert Parry, Charles Villiers Stanford, and Edward Elgar. Her opera The Wreckers (which predates Britten in its look at the pitfalls of populist justice in a coastal village) stands as her greatest achievement. One of her most arresting works, The Prison, is a choral symphony that focuses on the experience of a prisoner who is coming to terms with his imminent execution. In this case, Smyth was writing from experience: in 1912, she was imprisoned for three weeks for hurling a brick through a Parliamentarian’s window during a suffragette riot. Any sense of foreboding she may have felt when in captivity was exorcised through the music it inspired. Ironically, The Prison, expressive of Smyth’s agnostic point of view, resonates with an almost religious sense of peace and assurance.

The Mass in D grew out of a passionate reaction to hardship, albeit using a traditional instrument for solace. The pain she suffered in her personal life during the late 1880s — combined with the friendships and religious discussions with the family of the Archbishop of Canterbury as well as practitioners of the Catholic faith — led to Smyth embracing a belief in a divine plan and her place within it.

While the Mass did not signify an abiding religious belief, it stands as a personal document of devotion. The music, Zigler insists, offers “a very human journey for redemption and forgiveness.” Even when hearing it today, “one can feel redeemed.”

Aaron Keebaugh has been a classical music critic in Boston since 2012. His work has been featured in the Musical Times, Corymbus, Boston Classical Review, Early Music America, and BBC Radio 3. A musicologist, he teaches at North Shore Community College in both Danvers and Lynn.

Tagged: Amelia LeClair, Cappella Clausura, Ethel Smyth

And what a splendid performance it was!