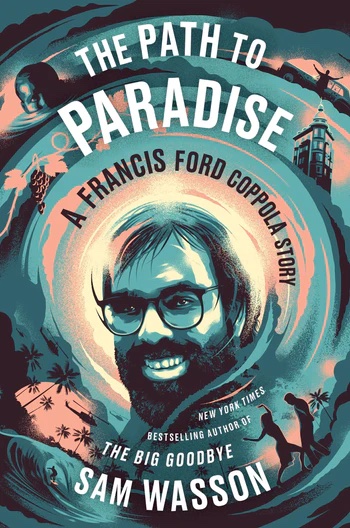

Book Review: “The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story” — Still Carrying On

By Gerald Peary

The Path to Paradise is yet another bio in praise of a high modernist male artist who is seen as that much more colorful because of his excesses and failures.

The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story by Sam Wasson. Harper, 400 pages, $32.99.

Reader, be forewarned. Are you seeking a comprehensive biography of Francis Ford Coppola including scholarly discussions of his movie? The subtitle of Sam Wasson’s book, The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story, clues you that you should look elsewhere. Please note that it’s “A” Coppola story, not “The” Coppola story. And that translates into Wasson being enormously subjective about what aspects of Coppola he’s going to emphasize and what things, some unarguably essential, he’s going to pretty much leave out.

Reader, be forewarned. Are you seeking a comprehensive biography of Francis Ford Coppola including scholarly discussions of his movie? The subtitle of Sam Wasson’s book, The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story, clues you that you should look elsewhere. Please note that it’s “A” Coppola story, not “The” Coppola story. And that translates into Wasson being enormously subjective about what aspects of Coppola he’s going to emphasize and what things, some unarguably essential, he’s going to pretty much leave out.

It’s a bit disappointing that Wasson doesn’t analyze any Coppola movie, but maybe that’s what to expect of someone who is a cultural historian and not really a film critic. Instead, he’s going to dwell on the making of films, not on the films themselves, a strategy that worked beautifully for his acclaimed earlier book, The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Days of Hollywood. But what a comedown with The Path to Paradise. Many of Coppola’s movies are practically skipped over, or given just a couple of cursory pages. And this includes, inexplicably, The Godfather and The Godfather II. The latter, perhaps Coppola’s greatest film and an abiding masterpiece of American cinema, is especially maltreated, almost ignored. Given no more weight than, say, a Coppola trifle, You’re a Big Boy Now.

So where is Wasson’s attention? There are many contradictory sides to Coppola that a biographer might wrestle with. Wasson consistently highlights the moments in an 84-year life when the filmmaker was craziest, acted craziest. The Coppola he forefronts is the manic high modernist borrowing irresponsibly and spending wildly, hiring and firing on a whim, buying and selling homes and office buildings and theaters and film studios, whatever, also creating a movable feast of pasta treats and the finest wine for hundreds at a time, smoking dope and, yes, cheating on his beleaguered wife. He is sometimes joyous amidst the chaos, other times depressed, even gloomily contemplating suicide. But the self-willed sturm und drang somehow opens a space for Coppola to create momentous Art. Or that’s what he seems to believe. Anyway, Wasson is there for the turmoil: the rise and fall of Coppola’s financially precarious film studio, American Zoetrope; the behind-the making of Coppola’s two most megalomaniac and runaway projects: Apocalypse Now and One From the Heart.

A conventional biographer probably would start with Coppola’s early life. The first pages of The Path to Paradise jump straight to Apocalypse Now, Coppola’s eighth feature. Seeking an entry point of maximum excitement, Wasson plunges the reader immediately into the Conradian madness of the shoot in the jungles of the Philippines. He tells the tale with Tom Wolfean huff-and-puff, a stab at New Journalese myth-making. But it’s a well-worn saga, all déjà vu. Who can get excited anew hearing about Coppola’s harrowing filmmaking, his making it through a crippling typhoon and nervous breakdowns among the cast and crew?

The one Apocalypse Now episode I did wish Wasson would elucidate is not in the book. I was curious for his take on the movie’s New York City press conference, which was like no other I’ve ever attended. 45 years later, I still smile about the Happening atmosphere, with many of the large cast hanging about doing nothing, with contentious questions for Coppola from the gathered journalists (including me) about the film’s sketchy politics, and a weird show-stealing appearance of a smelly and unwashed Dennis Hopper spouting stoned-out nonsense to the air. Months afterward, he was still in the outfit from the druggy days in the Philippines. (Brando was a no-show.)

It’s only at page 55 that Wasson finally gets to Coppola’s miserable New York childhood. Recall his father, Carmine Coppola, who composed music for some of his son’s movies and who became quite famous for his score, played around the world, for the Abel Gance silent epic, Napoleon. Well, Coppola the filmmaker son was incredibly gracious to his dad considering how badly he’d been treated by him as a youth.

Carmine was a self-absorbed, ever-angry musician and composer who moved his family about on a whim, even transporting them all to Los Angeles, driven by his obsession with achieving fame and success. He never asked how little Francis was doing, or cared much about any of his kids. Meanwhile, Francis spent a year sick in bed with his left side paralyzed. Says Wasson, “He was thick-lipped, friendless Francie Coppola — like his father, a disappointment, oyster-ugly…. He was the stupid one, he thought, stupid and ugly, a disappointment to both his parents. “

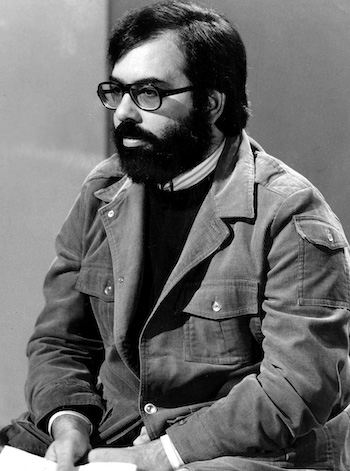

Francis Ford Coppola in 1976. Photo: Wiki Common

It was while he attended Hofstra University that the frog-like Francis miraculously transformed into royalty. Perhaps forever. As an 18-year-old he took over two drama organizations, wrestling them away from faculty control. Coppola: “I went from being this lonely kid who had no friends to being like the king of Hofstra…. I had all the keys. I ran everything.” He acted in plays, he directed them, he also discovered cinema. A campus screening of Eisenstein’s silent Ten Days That Shook the World made him dizzy with possibility. He wrote to the UCLA department of theater arts: “I would like to study Motion Picture writing, directing, and production. I see these three aspects as one, and so I would like to become a Motion Picture Artist.”

The early ’60s were the fledgling days of film schools and Coppola at UCLA made friends with his peers in LA, many enrolled at USC. Here was the first academically trained movie generation: George Lucas, John Milius, Carroll Ballard, Walter Murch. Spielberg hung about as a college dropout; also there was their pal Scorsese at NYU. Guys. Guys obsessed with cameras and the quickly developing film and video technology, Coppola perhaps most of all. He followed the path of other ambitious young filmmakers by apprenticing with “B” movie impresario Roger Corman. In exchange for doing for Corman the most menial tasks at laughable pay, he would be in line to break into cinema. Eventually, Coppola was allowed to hold the boom, and he shot second unit for Corman’s The Young Racers. He was rewarded for his loyalty by being allowed to direct his first feature, the exploitation cheapo Dementia 13. Then away from Corman, he made the low-budget You’re a Big Boy Now. The latter played at Cannes and it also got Coppola his MA from UCLA.

It is when Coppola moved both his filmmaking and his home to San Francisco that Wasson’s writing really wakes up. For the first time the director had some real money in his pocket, not from directing movies but for writing the script for Patton. It was here, before even The Godfather, that he built the first version of his utopian Zoetrope Studios, a gathering place for his young filmmaker friends to be creative. His wife, Eleanor Coppola: “He had always wanted to be in this wonderful community of artists at the moment people would talk about later as some golden era.”

But as always in Coppola’s future, it was a golden era with asterisks. He allowed his eager pals to work around the clock developing exciting personal projects. But Zoetrope was a non-union shop; film editor Richard Chew complained in the name of many employees about “minimum wage, long hours, hundred dollars a week, seven days a week.” This was when Coppola began to indulge in his habit of spending extravagantly on anything that smacked of emerging technology. Another Zoetrope employee, “We’d be working and it would suddenly be, ‘Oh look! Come see the new machines that Coppola bought!’”

Wasson is excellent at taking the reader through the SF years, especially after the two Godfather films, when Coppola was suddenly famous and getting Great Gatsby rich. He bought a 22-room house for his family, an 8-story office building for Zoetrope with a lavish office for himself. He bought SF’s City Magazine. And his own jet plane. “I am at the zenith in my opportunity to make big deals,” Coppola declared.

Francis Ford Coppola in 2011. Photo: Wiki Common

So let’s skip ahead a few years to when the filmmaker went really grandiose, gambling his accumulated fortune on moving American Zoetrope to LA, including the purchase of nine sound stages for his studio. In order to make his all-time pet project, his dream movie One From the Heart.

First, the hippy vibe continued on from San Francisco. Extras were hired by open call, unheard of in Hollywood. Zoetrope was a place of impromptu classic movie screenings and drop-ins by the likes of Godard and Wenders and also of movie-interested junior high kids. And — why not? — he put on the payroll film legends Michael Powell and Gene Kelly. Old-time director King Vidor arrived in a wheelchair for a visit and Coppola said to his staff, “We have to find something for Mr. Vidor.” But the real money (in the millions) was being thrown at the thin artificial romance which was One From the Heart. Making it, Coppola discovered a new way to direct his actors, by watching them on monitors inside his camper. He loved doing it that way, though the actors felt neglected, being talked to on a microphone.

But what extraordinary sets by Dean Tavoularis! The most beautiful and artful ever! The price of the film escalated from $15 million to $23 million. Wasson: “Coppola added 32 extra days of reshoots, additional special effects photography, and an elaborate opening title sequence…16,000 miniature light bulbs in all.” Finally, finally One From the Heart was ready to be unveiled. What a fiasco! A newspaper reporter: “…the parts that didn’t work at all were the dialogue, the acting, and the directing.” Critic Andrew Sarris: “Coppola has thrown out the body and kept the bathwater.” One from the Heart needed to gross 68 million dollars to break even. It took in $982, 492 in 5 weeks in theaters and then was exiled to home video.

The end of American Zoetrope? Not quite. It still exists today, though on a smaller scale, and returned to San Francisco. Even when Coppola sinks into debt, seemingly sells off everything, he still has infinitely more riches than you and I. In the last three decades, his few movies have faltered but his wine business has kept him a multi-multi-millionaire.

Finally, is Coppola a really good guy or an Ahab of a narcissist who has taken everyone down with him numerous times? Wasson, who did his research hanging around with the Coppola clan, is definitely forgiving of Coppola’s gargantuan shortcomings. Ultimately, The Path to Paradise is yet another bio in praise of a high modernist male artist who is seen as that much more colorful because of his excesses and failures. Coppola is let off the hook, given tacit permission to carry on forever with his boundless money and privilege.

Can I say that I’m a bit jealous?

About fifteen years ago, both Coppola and I were guests in Finland at the Midnight Sun Film Festival. It took place in a tiny town in the polar zone, and there was literally only one place for everyone to stay there. I remember taking satisfaction in knowing that both the world-renowned Godfather director and little film critic me were bedding down at the same crummy two-star hotel.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque; and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world.

Tagged: Francis Ford Coppola, Sam Wasson, The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story

Great review. You might have skipped the jealousy part.

I didn’t want to skip it because it probably informed my somewhat skeptical view of Coppola, High Modernist Genius.

I loved this book. What fascinated me was the “hippie vibe.” It’s strange, though, that Coppola was trying to recreate the studio system with Zoetrope. Still, I greatly admire his ambition. I could never be as adventurous as he was in the ’70s.