Book Review: “Drums & Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon” — Overcome by Madness

By Tim Jackson

Drums & Demons is at times frustratingly unclear on dates, but its research is comprehensive about the brilliant career and disastrous end of drummer Jim Gordon.

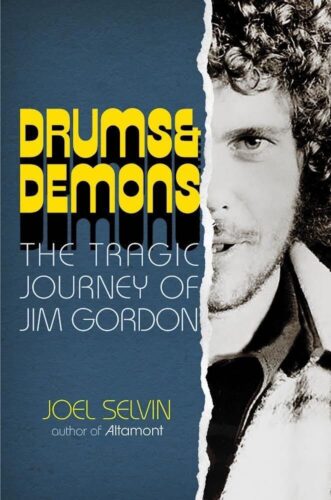

Drums & Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon by Joel Selvin. Diversion Books, 288 pages, $28.99. (hardcover)

Of the most influential drummers of the late 1960s and ’70s, among the key figures who come to mind are the Brits Ringo Starr, John Bonham, Keith Moon, and Charlie Watts. In the States, the list would include Dino Danelli, Levon Helm, Russ Kunkel, and Jim Keltner. West Coast drummer Jim Gordon, arguably this period’s most influential session drummer, is mentioned the least. That’s partly because it is difficult to reconcile his creative reputation with the crime that he committed in 1983. Armed with a hammer and butcher knife, he struck his 71-year-old mother in the head and then stabbed her in the heart. The police found him in his apartment sobbing, curled up in a fetal position. The crime has eclipsed all else. Joel Selvin’s book, Drums and Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon chronicles the drummer’s rise as a gifted young musician and it is an attempt to restore his standing. Only in the book’s final three chapters does the biographer dive into the musician’s tragic final days, when his undiagnosed schizophrenia finally consumed him.

Of the most influential drummers of the late 1960s and ’70s, among the key figures who come to mind are the Brits Ringo Starr, John Bonham, Keith Moon, and Charlie Watts. In the States, the list would include Dino Danelli, Levon Helm, Russ Kunkel, and Jim Keltner. West Coast drummer Jim Gordon, arguably this period’s most influential session drummer, is mentioned the least. That’s partly because it is difficult to reconcile his creative reputation with the crime that he committed in 1983. Armed with a hammer and butcher knife, he struck his 71-year-old mother in the head and then stabbed her in the heart. The police found him in his apartment sobbing, curled up in a fetal position. The crime has eclipsed all else. Joel Selvin’s book, Drums and Demons: The Tragic Journey of Jim Gordon chronicles the drummer’s rise as a gifted young musician and it is an attempt to restore his standing. Only in the book’s final three chapters does the biographer dive into the musician’s tragic final days, when his undiagnosed schizophrenia finally consumed him.

Drums & Demons focuses on Gordon’s remarkable musical contributions. It was a time when rock and roll was moving from the sounds of the ’50s, reinventing itself with an array of new artists, producers, and writers. Gordon worked with most of them: The Everly Brothers, Bobby Darin, Sonny and Cher, Delaney and Bonnie, Joe Cocker, Eric Clapton, Stevie Winwood, Richard Perry, Jack Nitzsche, Frank Zappa, Leon Russell, The Beach Boys, and Glen Campbell, to name just a few.

After serving in the Army, Gordon’s father, a staunch Republican and troubled alcoholic, moved the family from New Jersey to Los Angeles in order to give himself a fresh start. He was a distant and abusive parent who once told his son that rock and roll would cause the boy to burn in hell. The young Gordon was shy and withdrawn. Even as a teenager, he heard voices, but they were friendly. Selvin speculates that Gordon “developed a rich inner life” because of this psychological condition, even if it made him fearful at times. Drums were a place of self-worth and calm and the burgeoning music scene of L.A. was advantageous to a dedicated, hard-working young musician. Music remained medicinal throughout his most troubled days.

Before he was out of high school, Gordon was spotted playing at a small club by the Everly Brothers’ music director, Frankie Knight, who saw that Gordon had, as Selvin describes it, “a bounce, a lilt, a boiling undercurrent, and an instinct to drop bombs and when to hold back that couldn’t be learned.” Gordon was an excellent sight reader; he also had a solid musical understanding of where to push and when to leave space. Soon Gordon was in demand, and not just for rock and pop sessions. Artists as varied as Joan Baez, Judy Collins, Bobby Darin, and even Tiny Tim on his novelty hit, “Tiptoe Through the Tulips,” called on his services.

Selvin sets the stage with a short history of the development of the modern drum set. In the ’20s, drums were a collection of percussion devices like bells, ratchets, whistles, and wood blocks, known as a “contraption set” (these were also used to accompany silent films). A derivation of the term used today is the “trap set.” Gene Krupa, who helped design the contemporary drum set, worked with Avedis Zildjian to develop thinner, more practical cymbals. (Zildjian Cymbals has been in business since 1623, and the factory has been in Massachusetts since 1929.) By the ’60s, jazz and swing drummers were coming up with rock and roll rhythms. In Los Angeles, a group of session musicians — famously called “The Wrecking Crew” — were cranking out the backing tracks for dozens of artists. Earl Palmer or Hal Blaine was usually in the drum chair. Gordon became a protégé of Blaine, who quickly recognized, as the author describes it, Gordon’s “instinct for punctuation, decoration, and percussive commentary.”

Former swing jazz players, Blaine and Palmer were inventing rock and roll drums. Gordon grew up listening to these players, eventually developing a more deliberate rock feel accented by a strong backbeat. Gordon had other merits: producers valued his ability to anticipate what any song needed. In the studio, Gordon could organize his drum parts quickly and duplicate them perfectly in take after take. He was content to drive a song or disappear into it.

An early example is “Misty Roses,” performed by Bobby Darin. The percussionist holds back with a cross stick on the rim of one drum. Then the chorus breaks into quarter notes on the snare drum. The strategy is bolder than expected for a ballad, but Gordon recognized that a producer could choose to mix his sound back or bring it forward. His intuitive understanding of how to tailor his part to the artist’s taste gave all involved complete confidence. In many of Gordon’s early recordings the drums are heard deep in the mix: the percussion takes the form of an insistent and steady drive that adroitly underpins even the most delicate songs, such as when he backed up Collins and Baez.

Drummer Jim Gordon. Photo: Zappa Wiki

Gordon Lightfoot had questions about how best to use the drums in his song “Sundown” (1974). He was won over by Gordon’s approach of leaving out a single beat on the verses — which gave Lightfoot room for voice and acoustic guitar. The drums would then drive the chorus, supplying no extraneous fills or embellishments. Producer Richard Perry knew he could depend on Gordon. Perry was working with Carly Simon on the song “You’re So Vain,” and the sound he wanted was not coming from Simon’s drummer, Andy Newmark, or session player Barry Morgan. In interviews, Newmark recalls watching Gordon put down the track; he says he received a priceless education watching his fellow drummer organize and color the track with surgical precision. It took 60 takes over five hours. Jim Keltner, one of the most recorded drummers of the past 50 years, says that when he was a young drummer he found his own style by recognizing he would never duplicate the kind of consistency and finesse Gordon excelled at.

The laid-back L.A. sound was one side of Gordon’s playing. But he could explode when necessary on songs like Mason Williams’s “Classical Gas” (1968) or John Lennon’s “Power to the People” (1971). Gordon played sessions and toured with Frank Zappa. The notorious perfectionist had been very impressed with the 21-year-old Gordon’s sight-reading skills as he saw the drummer working through complex charts for producer Tom Wilson. Gordon’s hard rock playing on “Apostrophe” is another side of his style. When called for, he could combine accompanying difficult written passages with lengthy improvisations.

In the late ’60s and early ’70s, rock music changed. The Wrecking Crew lost its cachet when bands came on the scene with original compositions that matched their distinctive sound and image. Leading the charge was, of course, The Beatles. The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Eagles, and others sold millions of records. That success meant less demand for the session players who had been the recording backbone for bands whose material had been supplied by a stable of professional songwriters.

Gordon biographer Joel Selvin. Photo: Diversion Books

Gordon still thrived: he was a chameleon who could play in any style. Leon Russell, who Selvin labels “the circus master,” had assembled a stable of musicians (including singer-songwriters Delaney and Bonnie) and brought in Gordon. That led to a tour with Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs and Englishmen, followed by Eric Clapton’s project, Derek and the Dominos. Gordon’s work with Clapton, claims the author, “had a rhythm section operating on almost telepathic levels, and Jim, freed from the microscopic intensity of the recording studio, was unchained and unbound, exploding on the drums in all directions at once.” Gordon was no longer a session drummer but part of an elite circle of world-famous musicians. Clapton, at this time, had a severe drug problem, and Gordon was also taking harder drugs. As all this happened, the drummer “grew more private and self-contained.” Though he cared deeply for his only daughter, Amy, born in 1968, Gordon’s marriage was falling apart.

One time, after Gordon had spent hours setting up and tuning a new 10-piece drum set, Clapton walked into the studio. He was taking considerable time tuning his guitar. “You want me to tune that damn thing for you,” Gordon barked. Clapton had had enough. Despite being co-writers of the hit song “Layla,” the pair had been in constant bitter conflict. Clapton fired Gordon on the spot; the drummer then joined Stevie Winwood’s Traffic.

The music scene throughout the ’70s was awash in drugs of all kinds. On top of that, Gordon’s appetite for liquor was also enormous. The drummer was now snorting cocaine and shooting heroin as well as drinking quarts of liquor. His volatile temper could flare up at unexpected moments. Some of these stories are frightening. Yet, when he was recording, Gordon’s skill never faltered. Despite the drummer’s mental health issues and substance abuse, Gordon’s work with these bands feature some of his finest and best-known accomplishments: “Bell Bottom Blues” (1971) and “The Low Spark of High-Heeled Boys” (1971) being prime examples.

Drums continued to offer solace for a troubled mind. He contributed to the recordings of the top names of the era: Nilsson, Bachman Turner Overdrive, Burton Cummings, the Bee Gees, Manhattan Transfer, Hall and Oates, Steely Dan, and so many others. For every artist his drums served as the song’s nimble engine. That he maintained this high level of creativity given his psychological fragility is remarkable. Though Drums & Demons is at times frustratingly unclear on dates, its research is comprehensive. For those who want to follow-up on Gordon’s career, a playlist of his recordings is provided at the end of the book.

By the early ’80s Gordon’s auditory hallucinations were growing louder and more vehement. The drummer became increasingly unpredictable and delusional, to the point of becoming suicidal. Percussionists Gordon once influenced began to take over his session work. The details Selvin supplies of his subject’s final demise are heartbreaking. Following his arrest in 1983, the drummer was sentenced to 16 years to life. He never attended a single parole hearing.

Over the past two years, a couple of nonfiction films, The Wrecking Crew and Immediate Family — both directed by Denny Tedesco, son of Wrecking Crew guitarist Tommy Tedesco — have examined the careers of musicians who contributed to a very prosperous period of L.A. pop music. Drummer Jim Gordon, who died last year after spending nearly four decades in institutions and prisons, is barely mentioned.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story. And two short films: Joan Walsh Anglund: Life in Story and Poem and The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Great to hear that the talents of drummer Jim Gordon are being published. By the Bay Area reporter/music reviewer Shelvin, who’s known to research his topics. I have resided in Solano County for years and have known that the CDC facility in Vacaville had housed Jom Gordon. I’m pretty sure it was a dismal existence for him there. And it was there that he passed away. I just hope that some sort of royalties from being a coauthor of “Layla” would provide his prison account some form of income. My heart goes out to the mentioned daughter, who no doubt deserves any inheritance to his estate. He has been set free from the mental pain. Thank God

That’s all so amazing….. Layla… C’mon man…. But the guy that printed bell bottom blues on drums? C’mon man, that’s the tune reverses the upbeat/downbeat. It’s a work of art and difficult. That song alone is enough to recognize and remember this dude. 🤟

I met Jim in NYC while he was working with FZ. He was a very nice guy. A killer player onstage. Let it be a lesson to all the young players coming up. Don’t do drugs! Especially cocaine.

While the pernicious effects of cocaine abuse cannot be questioned, and Gordon’s drug intake was certainly a factor in his undoing, I have a feeling he was using substances to self-medicate rather than as recreation. I suspect the inner voices would have caused their havoc with or without drugs. Key phrase: “I suspect.” I wasn’t there. But Gordon’s top-flight percussion work is still out there for the listening. Can’t wait to dive into Selvin’s book!

Cocaine was impossible to avoid in the ’70s and, I agree, calmed a brain already in trouble. In interviews, Selvin says that other players could find him distant and without great interpersonal skills. His immersion into the instrument and intuitive understanding of the needs of a composition remain inspirational. It’s so unfortunate that the gift ultimately cost him his sanity and his mother’s life. She always thought his issues were drug-related; schizophrenia was not dealt with then as it would be now.

Great piece, Tim, using Jim Gordon as a window into a fascinating history of drumming. You are the one who knows with a half-century behind the drums. And going very strong, as evidenced by the recent Burren concert of your immortal Band That Time Forgot.

Wonderful piece. It allowed me hear the music in my head while I read! I suspect Selvin underplayed Gordon’s 1980s madness because he did not know very much about Gordon’s inner life during those mentally dissembling years. Or was it out of respect to the late artist? Was the period where Gordon lost jobs and sanity gone into at all?

Selvin did go into his last days. The book even starts with his stint playing for an unknown local group to which he had resigned himself. There, he showed evidence of erratic behavior, but the band knew he was a gift to their ensemble in any form. He was able to work recording sessions even during his decline. In my review, I prioritized his playing. The final chapters on his decline are a horror story and are best left to the author. In interviews, Selvin said that much of his research was new to Gordon’s associates and to his own daughter. She didn’t want to participate but appreciated the insights. He wasn’t great at communicating. In death, with facts revealed, there is a new appreciation of his talent.