Jazz Album Review: The Complete Massey Hall Recordings — The Legendary Concert Never Sounded So Good

By Michael Ullman

I heartily recommend this Craft Recording, even if (perhaps especially if) you have owned the LP version from (almost) a half century ago.

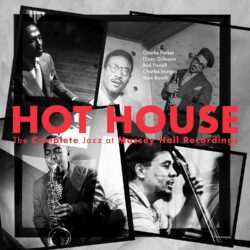

Hot House: The Complete Jazz at Massey Hall Recordings (2 CDs, Craft Recordings).

It still sounds like a bebopper’s fantasy: a concert in a decent hall featuring the greatest beboppers of all time: Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach. The Massey Hall (Toronto) concert of May 15, 1953, with the quintet and subsequently a trio set featuring Powell, is deservedly legendary. It’s surprising it happened at all. The Massey Hall concert was produced by the Toronto New Jazz Society, which had lost money in their previous concert featuring pianist Lennie Tristano with Lee Konitz. Though some of its members were disgruntled and even fearful, this new show was also originally intended to feature Tristano and bassist Oscar Pettiford with Parker and Gillespie. Tristano himself suggested that Bud Powell would be a better fit. Somehow Mingus replaced Pettiford. Astonishingly, to those of us who dream of hearing such a group, the doubters among the New Jazz Society were quite right: the audience was small, and the Society didn’t take in enough cash to pay the musicians. (If I read it correctly, several of the participants were handed bad checks.)

The Toronto group taped the concert. Charles Mingus, who was struggling to make his and Max Roach’s independent record company, Debut Records, a success, was given the tape in lieu of payment. He issued the quintet’s segment of the Massey Hall concert, first on 10-inch LPs and then on a single long-playing record. But first, he discreetly dubbed over his part in order to make the bass stand out. In 1990 Fantasy Records put out an 11-disc set: The Complete Debut Recordings. It included the seven quintet recordings in both the overdubbed and the original versions, the six trio sides, and Max Roach’s wonderful solo, “Drum Conversation.” Craft Recordings has done the same thing. The entire second disc here is the overdubbed version of the quintet’s concert. I bought the Massey Hall LP not too long after it was released. I can now confidently conclude that I prefer the original version. Mingus’s dubbing muddies the water. The band sounds clearer and more compact in the undubbed recording. It’s as if a veil were taken away.

Mingus, according to the notes in the Craft reissue, was not happy that the band only played such bebop classics as “All the Things You Are” and “Hot House.” I have a possible explanation. Powell, who had been recently hospitalized for his mental illness, seemed disengaged on the night of Massey Hall — except when he was playing. In 1963, saxophonist Dexter Gordon assembled a group that included Powell in the Paris CBS studio to make Our Man in Paris. He explained to me that, at the rehearsal, Powell seemed unable to play any of the new music Gordon had written. It looked like a disaster, but Gordon still went ahead with the session the next day. He had the band play bebop classics, including “Scrapple from the Apple” and familiar standards like “Willow Weep for Me.” The result, as Gordon modestly asserted to me when I interviewed him, was a classic: baffled by new music, Powell was able to improvise brilliantly on tunes and with chord changes he already knew.

Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, and Max Roach at Toronto’s Massey Hall. Photo: courtesy of Craft Recordings

The Massey Hall quintet sounds relaxed from the opening number, “Perdido,” whose familiar melody is met with a burst of applause not just once, but every time they play the recognizable phrase. Parker introduces Dizzy Gillespie’s “Salt Peanuts” by saying the tune was composed in 1942 by “my worthy constituent.” Later, as Parker solos with his miraculous fluency and seemingly effortless lyrical grace on that novelty number, we hear Gillespie yelling in the background. The quintet was having a good time, the players digging with gusto into the music. Of course, Parker is astonishing — virtuosic, yet balanced, like a champion boxer. His articulation of fast phrases, such as when he states his part of the melody of “Night in Tunisia,” sounds wonderfully poised. His relaxed solo on “Wee (Allen’s Alley)” stands as a challenge to every other jazz saxophonist. Gillespie is at a peak as well. I admire the unexpectedly sweet way he plays the melody of “All the Things You Are.” It’s the gentlest version I know. Mingus shines in his solo on the nine-minute “Hot House.” All praise is also due to drummer Roach: his precisely swinging introduction to “Salt Peanuts” is miraculous, given its ferocious tempo. “Go Max,” someone calls out at the beginning of Roach’s solo performance, “Drum Conversation.” The discussion is among his drums; his snare is overseen (as it were, or commented on) by tom toms. Roach is among jazz’s most orderly drummers, but he remains as exciting as any because of his brisk articulateness. With the quintet he solos on “Wee,” and in the trio with Bud Powell and Mingus, on “Cherokee.“

Disc one ends with six numbers by the trio, beginning with “I’ve Got You Under the Skin.” Powell gives no audible sign of his recent illness: he sounds lighthearted playing the theme statement of this Cole Porter tune. In the unaccompanied part of his solo Powell even produces some Art Tatum-like runs. Mingus’s equally buoyant lines can be heard clearly: the mike must have been close to his bass. Mingus solos enthusiastically on “Embraceable You.” In most of the trio sides, Roach is underrecorded. Powell plays the only piece that is even slightly obscure — his short version of Jerome Kern’s “Sure Thing,” which Neal Hefti had recently arranged for Count Basie. Perhaps he was uneasy because it stops abruptly, as if the pianist couldn’t wait to get to the bebop flag-waver, “Cherokee.” Here the recorded sound shifts; somehow the mike had been moved so that we hear Roach prominently.

I heartily recommend this Craft Recording, even if (perhaps especially if) you have owned the LP version from (almost) a half century ago. To my ears — and on my audiophile system — the original version of the Massey Hall concert, before overdubbing, has never sounded so good, or so compelling.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bimonthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Bud Powell, Charles Mingus, Charlie-Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, Hot House: The Complete Jazz at Massey Hall Recordings

I’m one of those people that own the LP from a half-century ago: the Prestige twofer The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever. It was my gateway drug into hardcore jazz when I was just a kid. You always hear those stories from jazz fans about the first time they heard Charlie Parker and their minds exploded—this was that album for me, esp. Bird’s solos on “Salt Peanuts” and “Night in Tunesia.” It’s also the album that made me a Dizzy Gillespie nerd all through high school (and beyond).

I’ll be getting this album, like TODAY. My old LPs are in tatters.