Theater Review: Stephen Sondheim’s “Here We Are” — The Canon Is Complete

By Martin B. Copenhaver

As satisfying as this incomplete work is — much like Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony,” which the composer inexplicably abandoned six years before his death — we can still regret not being able to experience the completed work.

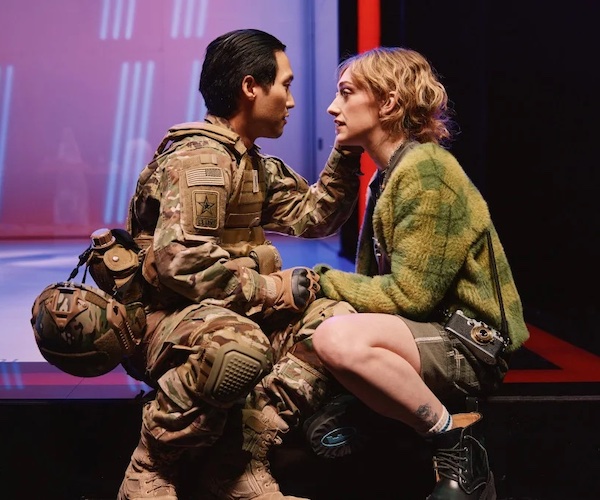

Micaela Diamond and company of Here We Are. Photo: Emilio Madrid

Attending Steven Sondheim’s last show — Here We Are, currently in a limited run at the Shed Theater in NYC — is a multilayered experience. It is a workshop production of an unfinished work, inside a slick world premiere, wrapped in an aura of tribute to a revered artist who has recently departed. It shouldn’t work but, in most respects, it does.

Sondheim often chose unlikely subjects for his musicals, such as penny dreadfuls (Sweeney Todd), a pointillist painting (Sunday in the Park with George), a chorus line of killers (Assassins). The sources of this last work, however, are so improbable that it can seem like Sondheim agreed to tackle them on an impulsive bet. The first act of Here We Are is based on the Louis Buñuel film The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), a biting satire that follows an obliviously privileged group in their continually thwarted attempts to get a meal. The second act, based on another Buñuel film, The Exterminating Angel (1962), follows the same group trapped at a meal that, for reasons that remain mysterious, they cannot leave.

Both films skewer the vanities and ennui of the flaky upper crust of society. No problem there. That is familiar Sondheim territory, well traversed in Company. The satire here, however, is thoroughly up-to-date. One couple had their poodles genetically copied so they can have identical dogs in residence at each of their houses. Another character screams to no one in particular, “Oh my God, my phone is dead!” as if that were a fate of tragic proportions.

This is not the first time Sondheim has based his work on a movie. In Passion, he adhered quite closely to the Italian film Passione d’Amore, on which it is based. That is less true here. The Buñuel films include heavy doses of surrealism (one of Buñuel’s early films was a short subject made with Salvador Dali), which does not translate easily to the stage. As New York Times theater critic Jesse Green points out, “Musical theater is surreal enough already.” If we can accept characters bursting into song in the middle of a conversation, why should we be startled by a bear that inexplicably wanders through the house?

So, rather than heap surrealism upon surrealism, Here We Are dispenses with most of the surrealistic images of the films. The situations the characters find themselves in are absurd enough.

The irony would not be lost on Sondheim that the first act of this show is about a group of people who never actually arrive for a meal (“Here’s to the ladies who can’t lunch!”), written by someone who was unable to arrive at an ending for the show. The sung music stops 20 minutes into the second act. But why?

Other notable works of art were never completed and for different reasons. Michelangelo described some of his most powerful works as “non-finito” (that is, literally, “unfinished”), and intentionally so. For instance, in the Accademia in Florence there are four massive statues (variously referred to as “Slaves” or “Prisoners”) that can look like works in progress. The figures are roughly hewn: much of the marble blocks in which they are embedded remains untouched. Nevertheless, these are fully realized works. Michelangelo’s intention was to create figures who seem to be emerging from the block of marble or who are stuck in the marble and unable to escape.

Joe Montello, who directed Here We Are, and David Ives, who wrote the script, would have us believe that the show is “non-finito,” an idea they originally pitched to Sondheim. Never mind the simpler explanation: Sondheim was a notorious procrastinator who was unable to compose much music in the last three decades of his life. No, they contend, the composer was not able to write songs for the second act because music does not fit with the story. The characters don’t sing because they wouldn’t sing under such circumstances.

A scene from Here We Are. Photo: Emilio Madrid

It is an absurd contention befitting an absurdist drama. The British composer Thomas Adès has written an operatic adaptation of The Exterminating Angel and, as one might expect, the characters sing. Quite simply, Here We Are was not so much finished as it was declared finished. As satisfying as this incomplete work is — much like Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony,” which the composer inexplicably abandoned six years before his death — we can still regret not being able to experience the completed work. In fact, it seems to me that the premise of the second act has more potential for music than does the first act. A group of people trapped together is a common conceit in everything from murder mysteries to Sartre’s No Exit because it is replete with dramatic potential. It would have been wonderful to hear how Sondheim would have worked with that premise.

Also, it is lamentable that Sondheim did not live long enough to complete this production. He was a genius who worked best under pressure. Some of his best work — e.g., “Being Alive” from Company and “Send in the Clowns” from A Little Night Music — was written during out-of-town tryouts when the deadline of opening night loomed.

The songs that Sondheim did compose for Here We Are exhibit his characteristic wit, such as when a bishop sings about why he is a terrible priest. There are examples of Sondheim’s signature word-play (a waiter sings, “We do expect a little latte later/But we haven’t got a lotta latte now”). There is also a poignant duet, saved from sentimentality because it is sung by a most unlikely couple.

Throughout the score there are motifs or phrases that seem to be musical references to other Sondheim shows, giving his last show the feel of a retrospective. We will never know if that was Sondheim’s intention. Jonathan Tunick, Sondheim’s long-time orchestrator, and Alexander Gemignani, music director and the son of Paul Gemignani (who conducted many Sondheim shows), also left their mark on the score.

The cast is comprised of A-list actors, certainly a starrier company than would usually be found in an off-Broadway show. Their various Emmy and Tony awards would fill a large trophy case. David Hyde Pierce is brilliant as the bishop manqué, able to make a weak character winsome. Rachel Bay Jones as Marianne carries the second act almost single-handedly — without the help of any Sondheim songs. Dennis O’Hare, who plays an unnamed waiter and then a servant, is, by turns, funny and threatening.

David Ives’s script is witty and engaging. This is especially evident in the second act after the music has stopped. A particularly affecting dialogue between the bishop and Marianne could only have been improved upon if Sondheim had set it to music. My only quarrel with the script is that the only truly despicable character in Ives’s version is the servant played by O’Hare, which is a complete and inexplicable reversal of Buñuel’s focus on the loathsome characteristics of the rich.

It is difficult to know what the ultimate verdict will be on Here We Are. Perhaps this production benefits from the proximity to Sondheim’s death, with audience members (including this one) yearning to hear something more — anything more — from the master. Or, perhaps it will grow in stature over time, like its uptown sibling, Merrily We Roll Along, which is enjoying a hit Broadway revival after 40 years in the wilderness. (See Arts Fuse review)

In any case, the Sondheim canon is now complete. In the future, we will have to be content with revivals, which is an inadequate word in Sondheim’s case. “Revival” seems to imply that something returns after being away. We don’t refer to a Shakespeare play being “revived” because it never left. It now appears that will be true of Sondheim musicals, as well.

Martin B. Copenhaver, the author of nine books, lives in Cambridge and Woodstock, Vermont.

To me, that butler was loathsome because all people, regardless of class or social standing, can display loathsome characteristics.

Yet I agree with the rest of your insightful review. Though is the canon complete? Sondheim did write an entire score for a film that was never made. We’ve heard “Sand and Water Under the Bridge” from it. But where’s the rest?