Film Anniversary: From Punchline to Plausibility — The 50-Year Transformation of “Soylent Green”

By Michael Marano

Soylent Green should be seen as a work of future history, a docudrama of things that, in 1973, had yet to happen but are happening now, 50 years later.

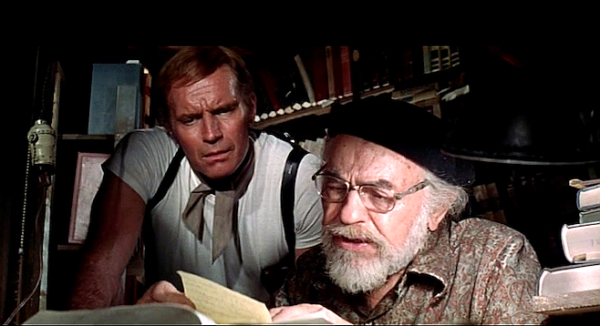

Charlton Heston and Edward G. Robinson doing some sleuthing in a scene from Soylent Green.

When working on an iteration of Invasion of the Body Snatchers in the early ’90s (eventually made by Abel Ferrara), screenwriter/director Stuart Gordon mentioned how Philip Kaufman’s 1978 Body Snatchers felt much more dated than did Don Siegel’s 1956 original. In ’93, the ’70s “California Pop Psychology and Hot Tub” vibe of Kaufman’s version seemed a relic of the Pet Rocks and Toe Socks era. But now, as the San Francisco in which Kaufman’s Body Snatchers was set is in the process of becoming a socio-cultural husk through gentrification, the 1978 version feels profoundly and scarily prescient. What’s the difference between a Pod Person and a Tech Bro whose idol is an affectless automaton like Elon Musk?

Richard Fleischer’s Soylent Green, released 50 years ago, has for decades been ridiculed as a relic of the bellbottomed ’70s. I hate to bring up spoilers, even for a movie half a century old, but Soylent Green‘s datedness was due in part to its final, shouted revelation of corporate cannibalism: “Soylent Green is people!” That slogan made Soylent Green fodder for SNL bits, multiple Simpsons gags, and even an NPR April Fools Day bumper. By 2013, the term “Soylent” has been so defanged that a real life company, which manufactures meal replacements, used the name.

Yet, like Kaufman’s Body Snatchers, Soylent Green has become grimly prescient.

Soylent Green is a police procedural set in 2022 in an overcrowded New York City (population 40 million) sweltering under the effects of global warming. And, though it was not as apparent decades ago, the prophetic Soylent Green turns out to be the most authentically film noir of all science fiction/noir films. Unlike Alphaville before it and Blade Runner, Dark City, Minority Report, etc. after it, Soylent Green was made by people who actually helped forge noir as a genre.

Fleischer made The Narrow Margin, Armored Car Robbery, and Trapped. He drew on those chops for his incredible “True Crime” trilogy of Compulsion, The Boston Strangler, and 10 Rillington Place, the last released just before Soylent Green. Lead Charlton Heston plays Homicide Detective Thorn; he’d been cast in Welles’s Touch of Evil, 1950’s Dark City, and Bad for Each Other. Thorn’s elderly roommate and “Police Book” (researcher for the presumably less-than-literate cops) Sol Roth is played by Edward G. Robinson, who, given his roles in Scarlet Street, The Stranger, Double Indemnity, and Key Largo, is probably the most “noir” actor outside of Bogey himself. Joseph Cotten, who plays Simonson, the billionaire industrialist who lives in a fortified luxury high-rise and whose murder sets the plot of Soylent Green in motion, had been in Shadow of a Doubt, The Third Man, and Journey into Fear. Tab, Simonson’s bodyguard, is played by Chuck Connors, who’d been in Walk the Dark Street and Death in Small Doses.

These film noir faces were, in 1973, iconic figures of the past: UHF-and-rabbit ears staples of TV’s The Late Show. But Soylent Green weaves the black-and-white anxieties of traditional noir into new contexts. Noir was an expression of disorientation and culture shock as Americans found themselves in the new reality of the post–WWII world, in a rapidly expanding American Empire of prosperity and comfort, courtesy of the burgeoning consumer power of corporate culture. Soylent Green flexes similar noir muscles, but to deal with the violent disorientation generated by an imploding American Empire of the Vietnam and Watergate era. The film posits a fragile future that would make post–WWII prosperity and comfort an impossibility. Soylent Green reflects what sociologist Alvin Toffler called “Future Shock” — the psychological trauma caused by too much rapid technological and social change. Post–WWII alienation of the past becomes alienation of the future, bridged by the genre conventions of noir and science fiction.

New packaging for an old product?

A particularly revealing victim of the film’s “Future Shock” is Edward G. Robinson’s Sol. Shots of him shuffling down darkened, trash-filled streets suggest the ending of Scarlet Street, in which the actor played a broken man, destitute and homeless. In Soylent Green he is “going home,” a euphemism for a government-assisted suicide center. He’s a learned Jew, trudging in rags to a state-sanctioned assembly line dedicated to the disposal of human bodies. At the euthanasia center, Sol chooses to be surrounded by projected footage of nature — as it used to be. Sol’s exhausted gaze, a fatigue that’s amplified when he sobs “how did we come to this?” as he gazes on fresh food for the first time in years, expresses a moral despair at what we have done to ourselves in the name of progress.

The film’s vision of alienation taps into the social anxieties of the late ’60s/early ’70s. For example, garbage trucks serve as tools of state and corporate oppression in Soylent Green. Sanitation vehicles haul human beings to the processing plants in which they are made into food, while modified garbage trucks are enlisted for riot control, with bulldozer-like blades that catch and lift protestors into containment bins. The image of oppressed populations loaded into garbage trucks was visceral in 1973, just five years after two African American garbage collectors in Memphis, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed to death in a malfunctioning sanitation truck because they were not allowed to sit in the cab with the white garbage men. These deaths led to the Memphis Public Works Strike, during which the Memphis cops used mace and tear gas against nonviolent strikers as they marched to City Hall. Martin Luther King would travel to Memphis to speak in support of the strikers… and be assassinated there. Soylent Green features a Black religious leader who is assassinated (shot through the head) because he is seen as a threat to an established order of oppression.

The vibe of the food riot in Soylent Green is Newark, 1967. It’s Detroit, 1968. It’s the Days of Rage in Chicago and People’s Park in Berkeley. In the midst of the food riot, a green kid assassin (Stephen Young), working for government and corporate interests, shoots into the crowd, trying to kill Heston, whose investigation into Simonson’s death threatens corporate control. The random deaths of bystanders by gunfire in a moment of social upheaval committed by a kid echoes the Kent State shootings; the descending batons as those bystanders die echoes the police responses to the protests that followed the Kent State shootings, in places like Buffalo, Manhattan, and Jackson, Mississippi.

In 1973, Roe v. Wade had been handed down in January, and the ERA had been ratified in 30 states. The year before, Title IX had been passed, and the right of unmarried women to use contraceptives had been affirmed in the Eisenstadt v. Baird decision. Soylent Green forecasts the political backlash that is continuing today. In the film’s plutocratic dystopia, women are commodified. Leigh Taylor-Young plays Shirl, a young woman referred to as “furniture”: she is an amenity, like a dishwasher, part of what is paid for when rich men rent a luxury apartment. (No men are “furniture,” suggesting that no women can afford, or are allowed, to buy into this arrangement. And our post-Roe world recommodifies women.

What’s more, in Soylent Green‘s one percent world, the rich and powerful can also become commodities to be disposed of by the rich and powerful. Particularly when they question the system’s exploitative setup. Cotten’s Simonson, barricaded as the world dies in a luxury tower the way today’s billionaires are hiding themselves in bunkers, is killed because he develops that most intolerable of qualities in a billionaire: a conscience. That makes him “unreliable” in the political/corporate plan to commodify tens of millions of people as food.

Charlton Heston in Soylent Green. He is not playing a climate change denier.

This reduction of human beings to fodder is precipitated by climate change. “It’s still 90 degrees out there,” gripes Heston in the middle of the night in one scene. Later, Taylor-Young offers to crank the AC of the luxury apartment to which she belongs. She wants it to “feel cold, the way winter used to be!” Crops dying due to extreme heat is mentioned, as is the Greenhouse Effect and multiple uncontrolled wildfires. The titular Soylent Green food product had been made of plankton but, because the oceans are dying, the power brokers have come up with another exploitable resource. Human corpses are ground into Soylent Green; the business plan calls for the eventual breeding of people like cattle to keep up with increasing demand.

Absurd… in 1973.

But in 2023 the oceans really are dying. This July, the temperature of the ocean off the coast of Florida hit 100 degrees — perhaps the hottest sea water ever recorded. This year brought us the warmest September in 174 years. There’s a more than 99 percent chance that 2023 will be the hottest year ever recorded.

And the notion in Soylent Green that people found so funny — corporate cannibalism? We now live in a time, driven by high tech and social media, in which consumers are consumed as products. The “Attention Economy,” a term coined by psychologist, economist, and Nobel Laureate Herbert A. Simon, runs on the harvesting of human beings — not physically, but virtually, psychologically. Our digital selves are cultivated by corporations and then sold as consumables. AI programs accumulate (steal) our words and pictures, digests them, and then sells them. Soylent Green 2.0. is a powerful economic driver. And ponder this grotesquerie: GV, Google Ventures, the Google’s investment arm, provided major start-up funding for the real-life Soylent meal-replacement company.

Screenwriter Stanley Greenberg added these layers of sociopolitical critique when he adapted Soylent Green from Harry Harrison’s (really quite facile) novel Make Room! Make Room! His politically weighted plays Pueblo and The Missiles of October are credited with creating a genre that he called “the theater of fact.” Others at the time called it “docudrama.” In 1979, Greenberg, who marched with MLK, said that “if the only purpose of historical drama is to record history … then there is no reason to dramatize the material…. But once you get into the human dimension … then you have to dramatize it.”

From this perspective, Soylent Green should be seen as a work of future history, a docudrama of things that, in 1973, had yet to happen but are happening now, 50 years later. Not in the ways Greenberg envisioned, but maybe now is the time not to smirk so readily when you hear the line “Soylent Green is people!”

Novelist, writing coach, personal trainer, and critic Michael Marano only caught bits and pieces Soylent Green on TV growing up, and only saw it all the way through when he picked up the DVD on a whim at the library a few years ago. Each and every person to whom he mentioned he was working on this article said, “Soylent Green is people!” like they were saying “Gesundheit!” after someone sneezed. He’s on Bluesky @mikemarano.bsky.social and Threads @madprofmike and at www.GetOffMyLawn.Biz.

Tagged: Charlton Heston, corporate cannibalism, Edward G. Robinson, Film Noir, Richard Fleischer, science-fiction

Great essay about a film I had forgotten! It may have indeed been prescient about global warming, if not overpopulation (New York City with 40 million people!?).

Insightful comments about how the almost unimaginable (and utterly repulsive) 50 years ago has become normalized, even if not in every detail. The overheating of the planet, for example, which I our governmental leaders were mostly not concerned about and addressing fifty years ago. (And are we now, really?)