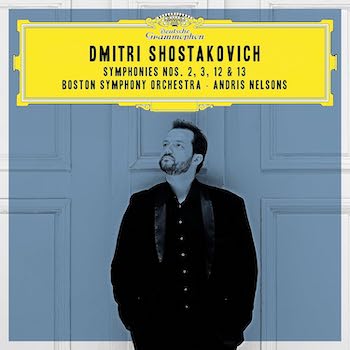

Classical CD Review: Andris Nelsons Conducts Shostakovich

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The final installment in the Boston Symphony Orchestra’ s Shostakovich symphonies series is not nearly as overwhelming as its kick-off disc.

Eight years ago, Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) kicked off an ambitious project to record the complete symphonies of Dmitri Shostakovich with an exhilarating account of the Symphony No. 10. That the final installment of the series, out in October, isn’t quite so overwhelming has about equally to do with the selections as with Nelsons’s interpretations of them.

Eight years ago, Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) kicked off an ambitious project to record the complete symphonies of Dmitri Shostakovich with an exhilarating account of the Symphony No. 10. That the final installment of the series, out in October, isn’t quite so overwhelming has about equally to do with the selections as with Nelsons’s interpretations of them.

To be sure, nobody programs Shostakovich’s Second or Third Symphonies on their musical merits. The composer himself chalked the former up as a creative failure though, conceptually, it has a few things going for it, including a dizzying climax involving 13 independent lines engaging in woozy counterpoint.

But there’s nothing particularly commanding about the actual content of either score, be that instrumental or vocal. The Second concludes with a setting of an execrable poem glorifying the cult of Lenin (Shostakovich wrote the piece to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution). Meanwhile, the Third celebrates the marriage of May Day and Communism with music of breathtaking vapidity.

That the BSO had no significant performance history with either piece before recording them isn’t surprising. Nor is the fact that the accounts here sound more like tentative explorations of unfamiliar terrain than vital interpretations meant to elevate this fare.

Whether the last can be done is an open question, though Nelsons’s penchant for broadening out tempos doesn’t advance the cause. Both symphonies — but especially the Third — need to at least feel like they’re moving and, clocking in at, respectively, 19 minutes and more than 35, neither of these performances do.

A similar stiffness pervades parts of the Symphony No. 12. Composed in 1961 to mark yet another observation of the October Revolution, the score is generally better written than its poor reputation (and certainly its tendentious, Lenin-to-the-rescue program) would suggest.

That said, Nelsons inexplicably does his best to hinder any appearance of edge, tension, or excitement that might crop up in the reading by again stretching things well beyond their breaking points: every movement goes at least a little over the average run-time. Most egregious is the second, which is prolonged to an almost-unbearable 14-plus minutes. The result is frequently a slog, though at least the lively spots in the outer movements stand out by contrast.

The conductor’s on generally firmer footing in the Symphony No. 13, which is the most compelling item on the album. Setting texts by Yevgeny Yevtushenko (most notably Babi Yar, a searing indictment of antisemitism that memorializes tens of thousands of Jews massacred by the Nazis outside Kiev during World War 2), the score takes an uncompromising moral stand at a time when the composer’s relationship with the Soviet regime was at its most ambiguous.

Throughout this performance, which was taped at Symphony Hall in May, baritone Matthias Goerne and the men of the Tanglewood Festival Chorus and New England Conservatory Symphonic Choir sing with stentorian power and focus. Goerne, in particular, brings a warmth and introspection that’s not always apparent in others’ renditions of his part.

Nelsons’s approach to the whole thing is sober and stately, and here his predilection for lingering is better supported by the music. (On the whole, his tempos are swifter than Riccardo Muti’s recent account but more spacious than Kurt Masur’s, Georg Solti’s, Vasily Petrenko’s, and Mark Wigglesworth’s.)

Interpretively, there are quirks: the tam-tam is strangely inaudible during most of the first movement’s shattering climax. And the second movement’s textures are weighted too heavily in favor of the brasses (its meter shifts also feel mannered).

But “In the Store” and “A Career” are strongly shaped. And the opening “Babi Yar” exudes a blend of defiance and righteous anger that is deeply affecting.

Having heard most of these performances live, it can be said that DG’s engineering manages to largely replicate the experience of being in the hall for the events. Additionally, as at Symphony Hall, whenever voices are involved, they’re judiciously balanced with the orchestra.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Andris Nelsons, Boston Symphony Orchestra