Jazz Album Review: “Pastor’s Paradox” — Paying Homage to Martin Luther King, Musically

By Michael Ullman

The intent of this fine album to dramatize the enduring legacy of Martin Luther King: no justice, no peace.

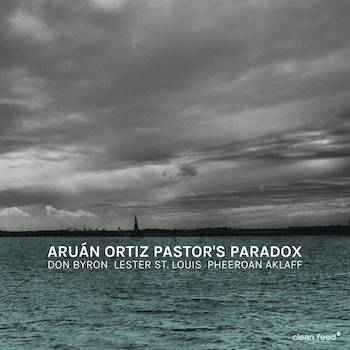

Aruán Ortiz, Pastor’s Paradox (Clean Feed)

Martin Luther King Jr. is the pastor who inspired this seven-movement suite by the Cuban-born pianist Aruán Ortiz. The musician draws on two famous speeches by King: predictably, his “I Have a Dream” masterwork of August 28, 1963, and the less well known “Drum Major” sermon of February 4, 1968. Actor Mtume Gant intones portions from both. (The other participants on this session are the wonderful Don Byron on clarinet and bass clarinet, Lester St. Louis or Yves Dhar on cello, and Pheeroan akLaff on drums.)

In both speeches, King celebrated the “marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community.” But there’s a significant difference. The Washington address was delivered to many thousands (really to the world), and King spoke of “this sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent.” He looked forward to an “invigorating autumn of freedom and equality.” (Autumn isn’t usually seen as liberating, but once you’ve committed yourself to the summer of discontent you don’t have much choice.) The metaphors King used are grand, though readily comprehensible, and the rhetoric magnificent. In one section, America is seen as being a bank of opportunity: “We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.” There’s wit as well: “We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote.”

In contrast, the “Drum Major” speech was spoken to the congregation of the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta. It was meant to inspire that congregation to be better. “There is deep down within all of us,” the pastor says, “an instinct. It’s a kind of drum major instinct — a desire to be out front, a desire to lead the parade, a desire to be first.” It’s in all of us, including his parishioners, and it has to be controlled and directed by all of us as well. This is King’s metaphorical explanation for, among many other things, aggressive acts such as the Vietnam War, which he vigorously and courageously opposed. (I remember supporters of King who thought that he should stick to race relations. To King, the war was an aspect of race relations.)

The first of Ortiz’s seven movements is entitled “Autumn of Freedom.” Sounds hopeful, but the music behind Gant’s reading is, to my ears, anguished. The cello begins with a kind of high-pitched whine over akLaff’s intrusive drums, Ortiz’s darting gestures, and Byron’s wildly off pitch lines. “Who said there is no time?” Gant asks repeatedly. That opening comes to an abrupt end. “Pastor’s Paradox” follows. It features Byron’s brooding, but inconclusive, bass clarinet solo over Ortiz’s shattering chords. It could be that the paradox refers to King’s activism, a willingness to disrupt that is rooted in Christianity’s need for self-correction and humility. Ortiz’s next movement, “Turn the Other Cheek No More,” may provide the way out of the contradiction. It begins with a held note by Byron’s clarinet (a D natural by my ears) over the rapid trilling of the cello and Ortiz’s chords. The piece seems to move via jumps and starts to held notes, before the band begins to improvise.

Cuban-born pianist Aruán Ortiz. Photo: courtesy of the artist

Parts of Pastor’s Paradox come off as program music, but there’s also state-of-the-art segments that feature group improvisation. AkLaff begins “The Dream That Wasn’t Meant to be Ours” with that rarest of musical happenings — a quiet drum solo, much of it on various cymbals and tom-toms. Then in comes Gant, asserting that “all have the drum major instinct.” In terms of being belligerent, Reverend King is probably referring to himself and his flock as well as those who oppose their liberation. “From Montgomery to Memphis” makes use of a repeated, anxious phrase by Ortiz, on which Byron comments while the cello takes on the role of bass and akLaff accompanies. The interlude becomes disorderly after two minutes, the resulting group improvisation perhaps suggesting the violence of Montgomery. We all know what happened in Memphis.

Ortiz does not leave us in this miasma of chaos and despair. There follows “An interlude of hope,” its restatement of the question”who says there is no time” followed by an answer, which was also Charlie Parker’s. “Now is the Time. No Justice, No Peace Legacy!” opens with the band members chanting the title rhythmically: a statement of political fact is transformed into a kind of percussion solo. Via well-spaced stereo, the speakers play with the words of the title: “No justice,” chants one, and another will say “no legacy,” or “no peace,” the words bouncing around in circular fashion. The intent is to dramatize King’s enduring legacy: no justice, no peace. With his small cast of exquisitely creative musicians, Ortiz makes this crucial point in satisfying musical terms.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Aruán Ortiz, Don Byron, I Have a Dream, Martin Luther King Jr., Mtume Gant, Pastor’s Paradox