Book Review: “Lena Horne — Goddess Reclaimed”

By Steve Provizer

One might conjecture that Lena Horne’s career was something like a mink-lined minefield: the promise of wealth and fame went hand-in-hand with the possibility of annihilation.

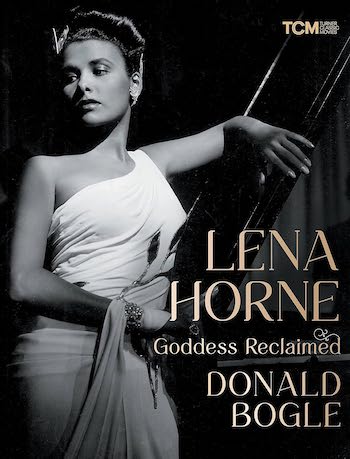

Lena Horne: Goddess Reclaimed by Donald Bogle. Running Press Adult, 478 pages, $35.

I wanted to read this book for two reasons. First, I’ve always been puzzled by my own reaction to the singing of Lena Horne. She had qualities that I admire in vocalists — technical competence and an investment in the lyrics. But I was never moved by her. Second, she held a unique position in American culture and I wanted to learn how she achieved that position and the effect it had on her.

Author Donald Bogle has written books about Black Hollywood, Ethel Waters, Dorothy Dandridge, and Black Female Superstars. He has produced here another profusely illustrated coffee-table-sized book in conjunction with TCM (Turner Classic Movies). Although the emphasis is on glamour (”Goddess Reclaimed”), the text supplied me with answers to my questions.

We learn about Horne’s disrupted and peripatetic childhood, including periods of abandonment by her mother Edna, who wanted desperately to have the career that her daughter ended up having. Edna arranged for 16-year-old Lena to audition for the chorus at the Cotton Club. The Cotton Club is a good exemplar of 20th-century Black artistic participation in the wider culture. It was owned by white criminals, who excluded Blacks from entry, except those at the very top of show business. Stage sets used the kind of “Plantation” motifs that marked Minstrelsy. Yet, within these parameters, Duke Ellington created art of a high order. Only attractive, “high yella” (light-skinned) women got into the chorus, and Lena Horne qualified. She later called the job “indentured servitude.”

Horne had no voice or dance training, but she had aptitude and was growing increasingly attractive. During the mid-1930s, she was cast as a dancer in a Black Broadway show, “Dance With Your Gods,” and a short film — Cab Calloway’s Jitterbug Party. She also sang with Noble Sissle’s Society Orchestra. Sissle, of “Shuffle Along” fame, performed standards, and his band was the first Black group to play the rooftop at Boston’s Ritz-Carlton. Horne also met Vincente Minnelli, who was trying and failing to put together a show for Broadway. Years later, as director of the film Cabin in the Sky, Minnelli would eventually play a large part in Horne’s career.

In 1937, Horne went to L.A. to be in the film The Duke Is Tops (nothing to do with Ellington). She had little to do in the film, but began to make friends in the Black “race” film industry. These included music director Phil Moore and choreographer-vocalist Marie Bryant, both of whom eventually worked in major film studios like MGM (Bryant would be the singer on the famous 1944 Djon Mili jazz film Jammin’ the Blues). There were about 900 theaters across the US that played “race” films, and efforts like The Duke Is Tops were important enough to the Black community that Horne’s participation inspired aggressive, positive coverage by the Black press, including the Pittsburgh Courier, Horne’s hometown newspaper.

Horne began to study singing more seriously and performed standards in a duo in Pittsburgh. As she became more aggressive about her career, Horne decided to move to New York City. Her first marriage, with Louis Jones, dissolved, and she had to negotiate custody terms. She retained custody of her daughter Gail, but not Edwin (Little Teddy), which remained a source of pain for her throughout her life.

In New York, she appeared at a benefit at the Apollo Theatre and was brought to the attention of white bandleader Charlie Barnet, who hired her as his singer in 1940. Along the way, Horne was meeting (and having affairs with) A-list musicians. After she left Barnet’s band in 1941, she landed at Café Society (”the wrong place for the right people”). This was an integrated club that drew a wide range of artists as well as political and intellectual figures, including the outspoken Communist sympathizer Paul Robeson. As described by Bogle, Horne seems to have had considerable grit in personality, but she felt somewhat at sea in this left-leaning racial and political milieu. Robeson helped focus Horne’s sense of unease. He inspired a process of radicalization that continued through the coming decades.

At this point, Horne was offered a singing gig at a big club in L.A. and she took the offer. She became a known quantity in the Black performing world and was invited to see Ellington’s 1941 revue Jump for Joy. There she met Ellington collaborator Billy Strayhorn and they began an intense friendship. Her affection for him was so strong that if Strayhorn had not been gay, Horne would have been happy to marry him.

While Horne was not very involved in film, she knew many people in the business, including Moore and Bryant from her time on The Duke Is Tops. Roger Edens, an important producer at MGM, was impressed enough with her nightclub performances to set up an audition with Arthur Freed, the man in charge of the studio’s musicals. It went well, but Horne thought things were moving too fast and she got her father (who had left the family early on) to come from Pittsburgh and help negotiate with Louis B. Mayer. She ended up being signed to a seven-year contract at MGM at a fairly modest salary.

At the same time this was happening, the Black press was lobbying the film industry to expand the roles it gave to Black actors, to go beyond the servile roles to which the performers had been restricted. Walter White (of the NAACP) came to Hollywood with presidential candidate Wendel Wilkie to meet with studio heads. At the NAACP convention in 1942, White told Horne, “You’re our test case.” In later years, Horne said, “I was just a pawn.”

Lena Horne and Eddie Anderson in 1943’s Cabin in the Sky.

A fairly long section in the book deals with the way MGM handled Horne’s hair and makeup. Apparently, it was the first time a major studio had to pay significant attention to how a Black actor appeared in front of the camera. The hairdressers didn’t know what to do; the head of the department had to work on her himself. Eventually, he hired a Black beautician to be with Horne on set. These efforts — to find makeup that would give Horne a “natural but glamorous look” — found little success. MGM decided to simply approach her as they would a white actress, only using a “browner base.”

Horne had much to negotiate. L.A. was segregated and there were only certain places she could go with white or Black friends. She lived in a white area and her neighbors circulated a petition to get her out of the area. To further complicate matters, Horne was being treated by the studio in a glamorous way that was threatening to “Black Hollywood” — those actors who were trying to make a living in bit parts, often playing servants. They wondered if they would be able to continue to work if there was change, and held “protest meetings,” which Horne attended. She evinced sympathy for the actors but, apart from two strong allies, Hattie McDaniel and Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, she felt besieged on all sides. In fact, when she went back to New York to perform at a benefit, she told Count Basie that she was ready to leave Hollywood. Basie was adamant that she go back, saying “You’ve got to stay.… You’ve been chosen and whether you like it or not, you’ve got to stay.”

Horne returned and began her period of intense film work. For the most part, she is not treated as an actress but as a singing-dancing performer. The exception is 1943’s Cabin in the Sky, directed (as noted) by Vincente Minnelli, with an all-Black cast, starring Ethel Waters. I won’t go into the plot, except to say that it is laden with old racial tropes interrupted by some sparkling music and performances. There was tremendous tension between Horne and Waters on set: the latter was adamant that she receive due deference as the movie’s star. She often exploded during the filming. Horne was sometimes on the receiving end of Waters’s fury. She noted how the power of a star’s ego could dominate a film set. In future productions, Horne would be as profanely insistent and controlling as Waters.

Horne returned to NYC’s Savoy-Plaza’s Café Lounge. Her contract with MGM was not so lucrative that it didn’t take the intervention of Andrew Goodman of Bergdorf-Goodman to provide her (on the installment plan) with a gown for her opening. The pattern was essentially set for all of her vocal performances to come. Horne would always be elegantly gowned and accessorized to ensure there would be no fall-off from her glamorous screen image.

When she returned to L.A., Horne’s “code-shifting” intensified as she traveled in elite film circles while still identifying with Black Hollywood. For the moment, Horne kept her counsel about racism, prioritizing her career. Given that in films she was largely a musical-dancing presence, she was surrounded by background Black singers and dancers. This may have alleviated some of the antagonism she felt coming from Black Hollywood. These scenes also were useful because of the studios’ concern over integration issues. Of course, Horne’s segments were often cut out of the films for Southern distribution.

During World War II, Horne appeared on radio and in USO canteens entertaining Black GI’s, which only elevated her importance to the Black community at large. White soldiers eyeballed pictures of Betty Grable or Lana Turner; Black soldiers had Lena Horne as their pinup girl.

Lena Horne as Glinda in 1978’s The Wiz.

Still, even in studios where she received star treatment, there were racist incidents, such as not being able to be served in the “white” studio commissary. Ironically, despite her success, there was little solid footing. Horne met and then spent time with Lenny Hayton, a white composer-arranger-conductor at MGM. Eventually she decided to marry him. Interracial marriage was illegal in California so they took their vows in Paris. In later interviews, she was candid in admitting that she did it to help her career. But she said she eventually grew to love him. They had to keep their relationship secret for as long as possible to avoid adverse public fallout.

At this point, Horne was performing in high-end nightclubs. Let me quote her about her approach to singing for the elite, because it addresses the question I posed at the beginning of this review: “I developed an isolation from the audience that was only a sophisticated cover for hostility, but the audience didn’t see it; they were too busy seeing their own preconceived images of a negro woman. The image that I myself chose to give them was of a woman whom they could not reach.… They get the singer, but they are not going to get the woman.”

This may be a formula for entertainment, but not for emotional connection. This is a reasonable explanation of my ambivalence toward her singing.

Life was already complicated enough for Horne when the late ’40s-early ’50s Red Scare entered the mix. She had friendships with many people involved in left-wing politics and had served on committees which — at that point in American history — might easily be tarred with the Commie brush. Her friendship with Paul Robeson was especially “problematic.”

With her movie career on the wane, television became an important means to revive her career. Scheduled to perform on TV’s The Ed Sullivan show, the Hearst newspaper the Journal-American mounted a campaign to keep her off the program. She was in jeopardy at that point of falling onto the blacklist.The only effective way for her to escape was through a “fixer.” Herald-Tribune columnist George Sokolsky published a “statement” by Horne. In it, she argued that Negroes had been making advances that would have been even greater if the Communists “didn’t deliberately try to confuse the issue and stir agitation.” A particularly bitter pill: she had to disavow her affiliation with, and admiration for, Robeson, insisting that he “does not speak for the American Negro.” She also composed a 12-page letter that was sent to the owner of a Las Vegas club and to executives at studios and networks. Bogle concludes: “It took a while, but apparently, Lena’s situation improved.”

Still, Horne was becoming more outspoken about and involved in civil rights. She threw an ashtray at a man in a restaurant who called her the n-word. She attended a meeting in Washington with RFK on the racial climate. She traveled widely to perform at civil rights benefits. The murder of Medgar Evers inspired her to a higher level of political investment. Meanwhile, her marriage to Hayton grew increasingly difficult because he couldn’t really understand her activism. She recalled: “Lennie had washed me. He didn’t see me as Black.”

She continued to do some film, stage, and television work and to record. She did many advertisements. Some boomers may remember her “What becomes a legend most” ad for mink coats. Her level of cultural recognition had reached icon level: she was referred to via a single name, as in “Liza,” “Liz” and “Lena.”

One might conjecture that Horne’s career was something like a mink-lined minefield: the promise of wealth and fame went hand-in-hand with the possibility of annihilation. Her 1981 one-woman show Lena Horne: The Lady and Her Music can be cited as the culminating event of her career. Bogle observes that in that performance Horne demonstrated an ability to laugh at herself and admit her vulnerabilities. In other words, the performer was finally willing to show the woman, not just the singer, something that might previously have cost her a career, her sanity, and her freedom. American culture, for its part, was showing its appreciation for the continued appeal and value of Horne’s art. Whether or not the culture finally understood that it is what had maintained the threat Horne feared for 45 years, that’s another question.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

I wonder why Lena Horne’s manager, William Dillworth is not mentioned in the article.

There is nothing in this book about WIlliam Dillworth.