Book Review: “That’s a Pretty Thing to Call It” — Prose & Poetry by Artists Teaching in Carceral Institutions

By Bill Littlefield

These essays and poems present incarcerated men and women as nothing more or less than our fellow humans.

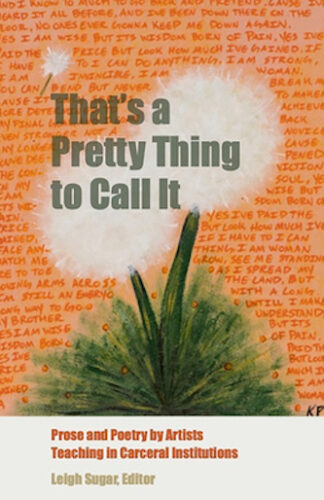

That’s a Pretty Thing to Call It: Prose and Poetry by Artists Teaching in Carceral Institutions, Leigh Sugar, Editor. New Village Press, 289 pages.

Working with incarcerated students presents distinctive challenges. The people who’ve contributed to this collection of essays and poems struggle with the debilitating notion that by meeting with their students in prison, they’re helping to make more tolerable — perhaps even more legitimate — a set of dehumanizing circumstances that nobody should have to tolerate. Some of the writers worry that they’re taking advantage of their students by using what they learn from their pupils to inform their poems and stories, thereby appropriating experience that’s not their own, since they get to go home at the end of each class. In one especially powerful moment in one of the essays, one of the poets discusses how a student accused her of using something he told her in confidence in one of her poems. The shame she feels provokes her to stop writing poems, at least for a time.

Beyond those specific issues, there’s the inevitable pain and sadness teachers feel when they come to know as friends and fellow learners men and women who live in cages and endure humiliations and deprivations wildly disproportionate to whatever crimes they may have committed decades earlier. To know in the abstract that prisons are dangerous, unhealthy, and destructive places is one thing; to know people you respect, admire, and like are forced to live under those conditions is something else entirely.

At several points in this collection, a line or an image brilliantly illuminates some truth about incarceration, such as when Zeke Caligiuer, one of Caits Meissner’s students, says of his daily life in prison, “Anything can be deemed threatening.” At another point, the same student argues against the automatic designation of “prison writing,” arguing that “the incarcerated are just as nuanced and different from each other as artists and personalities as the spectrum that exists in free literary circles.”

Some of the poems by the people who run workshops for incarcerated writers are especially worthy of attention. Idra Novey closes a poem titled “Parole” with this line: “To be quiet in a prison, Janet said, is to admit that you’re there.” It’s jarring to encounter the suggestion that the screaming and shouting and banging that goes on in some prisons might be understood as healthy protest rather than a terrible and constant, monstrous irritation.

In a poem titled “Growing Apples,” Nancy Miller Gomez describes the “big excitement in C block” when the incarcerated men discover a tiny plant that has grown through a crack in the concrete of one of the cells. They are “tipsy with this miracle” and they nurse the plant along, gathering “to stand over the seedling and whisper.”

These essays and poems present incarcerated men and women as nothing more or less than our fellow humans. Given the opportunity to embrace that humble yet radical assertion, most readers are likely to reject much of what characterizes incarceration in this country, and perhaps incarceration itself. Prisons are built to separate the incarcerated from the rest of the community, to silence their voices. Jails are an essential part of a system built to make them disappear. Works like That’s a Pretty Thing to Call It expose the cruelty and absurdity of that intention.

Bill Littlefield works with the Emerson Prison Initiative. His most recent novel is Mercy (2022), from Black Rose Writing.

Tagged: Leigh Sugar, New Village Press, prison writing, That’s a Pretty Thing to Call It