Book Review: “Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith” — Living His Own Personal Surrealism

By Gerald Peary

Biographer John Szwed proves masterly at decoding even Harry Smith’s zaniest works and he’s excellent at offering us the narrative of Smith’s raggedy and colorful life. The Life and Times is a very good read.

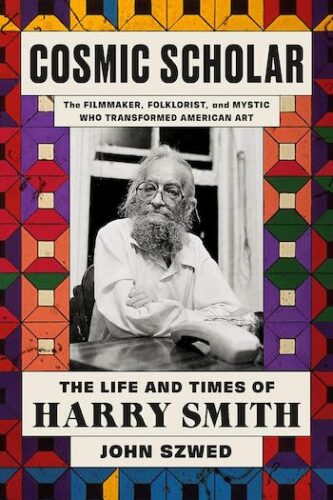

Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith by John Szwed. FSG, 416 pages.

It’s tempting to begin to explain Harry Smith (1923-1991) by using the catch-all, “He’s on the spectrum.” He didn’t notice what he ate or what he wore, didn’t care where he lived, had difficulties in human relationships, bragged that he never in his life had a sexual encounter. But whereas many “spectrum” people have one obsession that drives them, Smith was triggered by so many disparate fields. Here are a few of his intense loves: anthropology, painting, filmmaking, jazz, folk music, necromancy, ET, ESP. And collecting — cramming the dark tiny rooms which he occupied with floor-to-ceiling stuff, from rare 78s and arcane books to Seminole dresses and Ukrainian painted Easter eggs.

It’s tempting to begin to explain Harry Smith (1923-1991) by using the catch-all, “He’s on the spectrum.” He didn’t notice what he ate or what he wore, didn’t care where he lived, had difficulties in human relationships, bragged that he never in his life had a sexual encounter. But whereas many “spectrum” people have one obsession that drives them, Smith was triggered by so many disparate fields. Here are a few of his intense loves: anthropology, painting, filmmaking, jazz, folk music, necromancy, ET, ESP. And collecting — cramming the dark tiny rooms which he occupied with floor-to-ceiling stuff, from rare 78s and arcane books to Seminole dresses and Ukrainian painted Easter eggs.

If Smith is renowned for anything it’s as the compiler of the 6-LP The Anthology of American Folk Music, released by Folkway Records in 1952 and an influence on the ’60s generation of folk singers and rockers, most directly Bob Dylan. He’s also known by a smaller coterie for his abstract “non-objective” films, embraced by Jonas Mekas and the American underground. Perhaps Smith would be toasted for his myriad drawings and paintings, but only a few of them are not MIA, “lost.” The bulk of his art, also some of his films and countless invaluable possessions, ended up on the streets of NYC, thrust there by irate landlords because Smith did not believe in paying rent.

Smith didn’t seem to care that he was his own enemy. He would alienate potential art patrons by taking their money then purposefully producing nothing, or show up at his film screenings inebriated and insult the audience. And when he spoke about his art, his explanations were both madly incoherent and wildly esoteric, explained in a language beyond most earthbound mortals. Smith on one of his films: “The first part depicts the heroine’s toothache consequent to the loss of a very valuable watermelon, her dentistry and transportation to heaven.” Was he also just plain crazy? Smith himself thought he was. In the world’s oddest grant application, Smith declared, “I have always used my God-given gift of mental disease as perhaps the most valuable component of my work.”

So who could write credibly about such a strange and lunatic man, and both be sympathetic to Smith and actually grasp what he was trying to accomplish? Smith described the ideal chronicler of his work as a person who has “the consciousness to unravel its cryptograms.” Welcome ideal biographer John Szwed and his Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith. Unlike Smith, the autodidact dropout, Szwed has operated successfully within an academic frame. For 26 years, he taught anthropology, African-American Studies, and film studies at Yale, and he was chair of the Department of Folklore and Folklife at the University of Pennsylvania. These are great qualifications for getting at Smith. Just as important, Szwed is a veteran biographer of the most inscrutable of artists, having books out on both Miles Davis and Sun Ra.

Szwed proves masterly at decoding even Harry Smith’s zaniest works, and he’s excellent offering us the narrative of Smith’s raggedy and colorful life. The Life and Times is a very good read. Where it falters is understandable and forgivable: Szwed can’t quite get into Smith’s head. Could anybody?

Smith was born in Portland, Oregon, before his family moved to a rural area in the state of Washington. Living near Native people of the American Northwest, he got feverishly excited young about cultural anthropology. He was a teenage Franz Boas. A technology wiz, Smith taught himself how to tape record via a 78 rpm disc-cutting machine. At 18, he journeyed to the Lummi and Swinomish reservations to record their languages and songs. He taught himself to speak rudimentary Samish and Swinomish, studying nouns one year, verbs the next. The Native people seemed to appreciate him. Harry was invited to secret Lummi “spirit dances.”

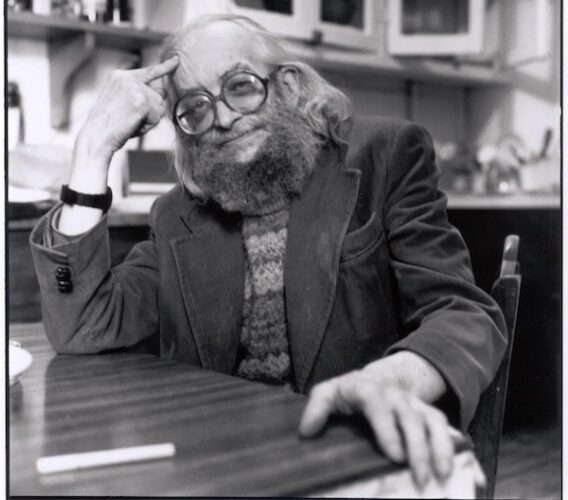

Harry Smith — he didn’t seem to care that he was his own enemy. Photo: Britannia

Short, stooped, with thick glasses, Smith was a loner at school. He only graduated high school at 20. He registered at the University of Washington as an anthropology major. Mostly a “C” student, he dropped out as a sophomore, never to return. He moved to San Francisco. A new addiction: modern jazz. He took up painting with a fervor, his task to capture on canvas the movement of his favorite jazz tunes. For five years he was consumed with painting Charlie Parker’s ultra-complicated “Koko,” a bebop tune played by Bird at 13 notes a second. Smith also devoted five years to watching avant-garde cinema at the San Francisco Museum of Art. When he finally made his own films, improvisatory jazz was the model for the rapid-fire barrage of images. Smith: “Some people who see my movies for the first time say they move too fast, but this is because they are using the wrong parts of their brains.” Several of his films were visual correlatives of the trumpeting of Dizzy Gillespie; later on, he incorporated into his cinema new musical loves — the Beatles, reggae.

By the end of the ’40s, his beloved jazz was not enough music to contain Harry Smith. Szwed claims (a little hyperbole?) that Smith was “trying to hear everything that had ever been recorded.” Among his delights: “Mexican police bands, Italian bagpipes, Asturian bagpipes and street organs.” But Americana too: country blues and C&W. In 1951, Smith moved across the US into the New York home of Lionel Ziprin, an expert on Jewish mysticism and the Kabbalah, which led Smith to another exploration: subterranean spirituality. Smith “copied magical engravings onto parchment paper, translating … texts from Latin, Hebrew, German, or medieval French.” Also, he built a landing pad for spaceships in a backyard. Who knew when extraterrestrials might appear?

Smith had transported from SF a priceless collection of Americana, rare 78 records produced between 1927 and 1932. He brought them to an enthralled Moses Asch at Folkways Records, who transferred them to 33-½ rpm. Folkways didn’t have musical rights, so these tunes became the bootlegged basis of The Anthology of American Folk Music. What songs were picked for the six volumes? “I determined what the norms were,” said Smith. Folk music in 1952 was understood by Americans as the melodic, politically minded, optimistic sounds of Pete Seeger and the Weavers, as well as Burl Ives. But Smith chose raw songs performed by Black and white recording artists, untamed tunes about killings, whoring, betrayals. Szwed said, “…the scratchy thinness of these old records seemed like the sound of history, the voices of the dead.”

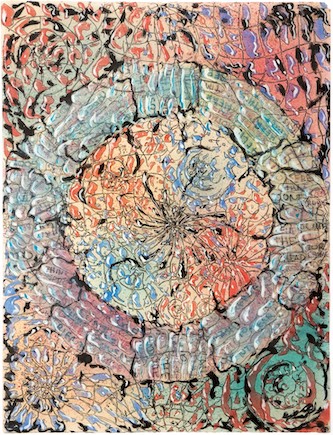

Harry Smith, untitled drawing, October 19, 1951, ink, watercolor, and tempera on paper, 34 × 27 ½ inches (86 × 70 cm), Private collection. Photo: courtesy Harry Smith Archives

Given its enormous 1952 cost of $25, only 47 sets of The Anthology sold the first year, mostly to libraries. However, Szwed observes that “Bob Dylan, the Byrds, Bruce Springsteen, Sonic Youth, Wilco, Nick Cave, Beck, and many others would come to claim Harry’s records as their Bible.” Dylan recorded at least 15 songs that were prompted by Smith’s Anthology. And the set also inspired rock critic Greil Marcus to coin the now well-oiled phrase “old weird America.” But Smith brought more to Folkways than his famous anthology. In the ’60s, he returned to anthropology, traveling to Oklahoma to record the Peyote-inspired music of the Kiowa Indians. Their songs were anthologized in a boxed set of three LPS with the unwieldy title The Kiowa Peyote Meeting: Songs and Narratives by Members of a Tribe That Was Fundamental in Popularizing the Native American Church.

While studying the culture of peyote, Smith freely partook of it. He also liked amphetamines, marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. His favorite lunch: soup and a Black Russian. Doing his projects, he was often high or drunk. He was usually in terrible physical shape, eating junk, not taking care of himself at all. He moved about like a vagrant, carrying what he could of his massive collections from place to place. No surprise, he spent some years at the Chelsea Hotel, befriending there Patti Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe. Then he skipped out into the night, owing management $7,000. Szwed: “One of the mysteries of Harry’s life is how he was able to live in New York for thirty-six years, never held a job, almost never paid rent.”

Although Smith was a royal pain in the ass, cranky and obnoxious, he got by with the aid of his friends. Jonas Mekas regularly lent him money and gave him an office to store his things, and Mekas repeatedly wrote Village Voice articles proclaiming Smith’s filmic genius. Allen Ginsberg was especially heroic in his support, allowing Smith to live for many months in his squat flat, though Harry drove him positively crazy. Ginsberg even arranged a sinecure for Smith to reside at the Buddhist Naropa Institute in Boulder, Colorado, where he had free house and board, surely Smith’s best arrangement ever. There he was anointed Shaman-in-Residence and treated with respect. But Smith, incurably self-destructive, abandoned Boulder for a return to New York supposedly for a dentist who could pull his rotten teeth. The dangerously rotten teeth remained and Smith died of heart failure at the Chelsea. Szwed’s epithet: “Harry … devoted his life completely to art, in some ways turned his life into a work of art, his own personal surrealism.”

A final Smith anecdote: He was said to be proud that Bob Dylan loved his Folkways recordings. But he screwed up their one chance to actually meet. Dylan came to visit Allen Ginsberg one night and Smith was asleep in the next room. Ginsberg went to fetch him, but he wouldn’t leave the bedroom. When Dylan and Ginsberg resumed their living-room conversation, Smith shouted at them through the wall that there was just too much noise.

P.S. — There are beautiful color illustrations in the book of some of Smith’s paintings and they seem astonishing visionary works. A sampling of Smith’s “non-objective” films can be found on YouTube with appropriate jazz and pop soundtracks.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque; and the general editor of the “Conversations with Filmmakers” series from the University Press of Mississippi. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world.

Tagged: Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith, Harry Smith, John Szwed