August Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Film

There is nothing in the least Marxist or counterculture cuddly in this brilliantly choreographed exercise in class manipulation.

Dirk Bogarde in The Servant.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of The Servant, the first collaboration between director Joseph Losey and playwright Harold Pinter. To mark the occasion, Criterion Collection has released a Blu-ray Special Edition that does right (via such extras as a revealing 1976 interview with the director) by this superbly sinister study in class parasitism, a darkly humorous battle for dominance that ends with an appropriately squalid reversal of fortunes.

There is nothing in the least Marxist or counterculture cuddly in this brilliantly choreographed exercise in class manipulation. A pair of opportunistic hedonists (Dirk Bogarde as Hugo Barrett and Sarah Miles as Vera) sink their claws into a young, weak-minded upper-class alcoholic (James Fox as Tony) who has the bad judgment to hire the pair on as butler and maid to take care of him and his classy London townhouse. The resulting soul-sucking psychosexual dynamics — engineered with playful panache by Barrett — owe as much to Jean Genet as they do to Ben Jonson and August Strindberg.

Pinter’s clipped dialogue resonates with flickers of hostility as Barrett slowly gains the whip hand through a series of cat-and-mouse games that, step by step, degrade Tony, separating him from his girlfriend and eventually his self-respect. Pinter’s inexperience writing for film is only evident when, on occasion, the narrative steps outside of the townhouse. These scenes tend to be broadly satiric — fuzzy rather than sharp. (Though Pinter supplies an amusing micro-cameo in a restaurant as a “society man.”) Other than that, the sneakily combative dialogue gives us the dramatist at his brusque prime. Visually, Losey transforms the elegant habitat — festooned with paintings that celebrate empire — into a claustrophobic cage, dramatizing Tony’s slow but sure fragmentation through funhouse mirror reflections, distorted images that convey how a psyche — and an antiquated social order — is being toppled topsy-turvy. The performances are first-rate, subtly stylized, with a feral Bogarde memorably sending up his leading man rep.

Pinter and Losey’s sardonic point is not that the hapless aristo is snobbish or cruel. It is that his comfortable position has separated him from reality. He is not so much innocent as oblivious, to the point that he seems to demand that others shape his desires/expectations. These are initially dictated by his conventional lover, then by his servants who, as Hegel informs us, know their master better than he knows himself. Pinter’s Social Darwinism is ironically pitiless: a man born to lead a genially hapless existence (his occupation amounts to talking about a fantasy investment in Brazil and visiting his solicitor) is trapped by wily predators serving in positions that themselves have become anachronistic.

The screenplay was adapted from Robin Maugham’s 1949 novel, which was wholly on the side of Tony, who is sympathetically depicted as a figure of privilege undercut by the machinations of the emboldened underclass. One of my favorite moments on the Blu-ray edition is a 1996 interview with Pinter about his screenplays with Losey. He talks (far too little) about writing The Servant, but when asked about where he stood in the conflict, Pinter barks out his answer with a smile — he was on the side of Barrett’s anarchy.

— Bill Marx

Jazz

Singer Nina Simone’s stunning performance at the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival has only now been released.

How’s this for a lineup: the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival featured, among others, Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Count Basie.

How’s this for a lineup: the 1966 Newport Jazz Festival featured, among others, Dave Brubeck, Stan Getz, John Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis, and Count Basie.

Oh, and Nina Simone, whose stunning performance at the festival has only now been released as You’ve Got to Learn. All in the span of a too short 30-minute set, Simone presents her audience with classical piano flourishes (throughout, naturally, but especially on the title track), American folk opera (on a rendition of her breakthrough song, “I Loves You Porgy”), gutbucket blues (Simone’s description of “Blues for Mama”), and protest (a “Mississippi Goddam” that swings).

With “Be My Husband,” Simone also gives, to quote Shana L. Redmond’s liner notes, “a ring shout,” that “throws into crisis [Simone’s] musical categorization as well as the distinction between the two iconic Newport gatherings, folk and jazz.” The performance is all voice with the barest bit of percussion, but that’s all that’s needed to create the song’s glorious groove.

Simone never required much backing for her voice anyway, as shown by her final selection, an encore of “Music for Lovers.” She sheds her band, who had supported her so sublimely throughout the set. (Check Lisle Atkinson’s bass on “I Loves You Porgy” and Rudy Stevenson’s and Bobby Hamilton’s guitar and drums, respectively, on “Blues for Mama.”) Accompanied only by her own piano, she hushes the crowd with her first-verse delivery of “There is music for lovers/In the hush-a-bye dreams/Of a child.” She builds the song upward from there, crossing a baroque bridge, before reaching the thunderous finale:

When the whole world discovers

That love is the only thing worthwhile

There’ll be music for everyone

And the whole world will smile.

The show ends there, as it must. What else is there for Simone to say?

— Adam Ellsworth

Public Art

Leo Villarreal and his team’s light installation in the Lindemann Performing Arts Center. Photo: Nick Dentamaro/Brown University

Brown University’s soon-to-open Lindemann Performing Arts Center is installing its first piece of public art. A compelling LED light sculpture, Infinite Composition is a site-specific, three-dimensional light work created by the internationally renowned artist Leo Villareal. He is responsible for several iconic pieces: they include The Bay Lights, which illuminated the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge for 10 years; Illuminated River, which uses light to visually unite nine bridges across the River Thames in London; and Stars, a series of animated light pieces adorning the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

This installation generates an endless variety of visual patterns, lighting up all 30 structural columns inside the lobby on the east end of The Lindemann Performing Arts Center, which was designed by Joshua Ramus/REX. Framed by a transparent glass clerestory that slices through the middle of the building, the installation can be seen from the street and adjacent campus spaces. It will serve as a beacon in the campus, an invitation to visitors that this is a space for new modes of art-making as well as innovative collaborations across “knowledge domains” and the creative imaginations of artistic communities.

Most of this artist’s other art and technology pieces have been environmental and thus, huge. In contrast, Infinite Composition‘s visually vibrant structural columns are on a much more human scale. In fact, they are literally in your face. And the impact is somewhat ambiguous: is this a science museum display? Or the interior of a casino? Digital art installations are proliferating, and that raises other uncomfortable questions: will these types of light art pieces devolve into visual totems, like the products of Pop Art and Op Art? Even worse, will these dynamic yet elegant columns — after a few years — become updated versions of Edwardian wallpaper? Just a fussy background?

But Infinite Composition may play a more positive role. Villareal has said, “Artists always talk about wanting to break down barriers and bring communities together with their work, and to see that happen in real time is always thrilling. Public art is powerful because it’s accessible to everyone, which means it can create a sense of identity in a community.” Hopefully!

— Mark Favermann

Classical Music

These are delightful pieces, showing Rossini’s precocious mastery of the syntax and gestures of High Classic style.

Rossini is not often thought of as a composer who started young, but his earliest operas are performed rather regularly, including his first, La cambiale di matrimonio, written when he was 18. Well, here are his six string sonatas, composed when he was a mere 12. He was living in the home of a wealthy man who played the double-bass, and so the works are for the unusual combination of two violins, cello, and bass (no viola). They are thus sometimes known as sonate a quattro and have been published in versions for standard string quartet, for wind quartet (basically a wind quintet minus the oboe), and for flute, violin, viola, and cello. The original instrumentation became widely known when the composer’s autograph manuscript surfaced at the Library of Congress in 1954.

Rossini is not often thought of as a composer who started young, but his earliest operas are performed rather regularly, including his first, La cambiale di matrimonio, written when he was 18. Well, here are his six string sonatas, composed when he was a mere 12. He was living in the home of a wealthy man who played the double-bass, and so the works are for the unusual combination of two violins, cello, and bass (no viola). They are thus sometimes known as sonate a quattro and have been published in versions for standard string quartet, for wind quartet (basically a wind quintet minus the oboe), and for flute, violin, viola, and cello. The original instrumentation became widely known when the composer’s autograph manuscript surfaced at the Library of Congress in 1954.

In whatever arrangement, these are delightful pieces, showing Rossini’s precocious mastery of the syntax and gestures of High Classic style, as seen in the works of Haydn, Mozart, Cimarosa, and many other composers who were prominent at the time.

Classical-music lovers may be more familiar with some of them from recordings by string orchestras. But hearing them as originally composed, with one instrument on a part, helps each voice come through clearly — there is not the comforting aural bath that tends to set in with a string orchestra. I am happy to draw attention here to a major recording of all six sonatas, released on the small Canadian label Leaf Music. (The CD seems to have flown under the radar of most critics. You can purchase it here, and/or download the brief booklet for free.) The performers use the 2014 critical edition published by the Fondazione Rossini Pesaro. The recording sessions stretched over five days in 2017.

I always loved these pieces, and love them even more now in this recording, which features two renowned Canadian musicians, Mark Fewer (who was a member of the Smithsonian Chamber Players for 15 years) and Joel Quarrington (who has been principal double-bassist of the Toronto Symphony Orchestra and the London Symphony Orchestra). Younger players Yolanda Bruno and Julian Schwarz match these two in accuracy and zest. I particularly enjoyed hearing each instrument step forth in soloistic manner at times and then gracefully rejoin the ensemble. Quarrington is remarkably precise in pitch; I often tense up when a bassist takes a solo, but not here!

The recording was made at the Lunenburg Academy of Music Performance (Nova Scotia) and sounds marvelous. Rossini later made fun of these pieces, calling them “dreadful.” (Though he admitted that he, despite being young, was the least bad of the four players that first performed them.) I think he’d change his mind about the works’ merits if he heard Fewer, Bruno, Schwarz, and Quarrington.

For those who prefer a fuller sonority, previous critics have sung the praises of a recording with string orchestra, in this same (original) scoring, and led by Salvatore Accardo. So now there’s a surfeit of good choices for hearing these most pleasurable pieces by a pre-adolescent Rossini.

— Ralph P. Locke

There is no question that these gentlemen love what they are doing — touring, recording, and singing. Every piece is approached with evident joy, and this infectious enthusiasm may well be the secret to Chanticleer’s very successful long run.

Chanticleer performing in Rockport. Photo: Shannon Adam

Founded in San Francisco in 1978, Chanticleer is known around the world as “an orchestra of voices.” The group’s seamless blend of (usually) a dozen male voices — ranging from countertenor to bass — tackles original interpretations of vocal literature, from Renaissance to jazz, from gospel to cutting-edge new music. This impressive range was on sumptuous display at their recent concert in Rockport.

Chanticleer has a devoted fan base, many of whom make the trek to hear this group at every opportunity. They were treated to a typically wide-ranging Chanticleer program. The concert began with a brief piece by Tinctoris (c. 1435-1511) followed by pieces by Josquin des Prez (c. 1450- 1521) and the ever-popular Anonymous (c. 1404). This piece, as well as much of the rest of the evening’s program, was inspired by the theme of labyrinths. Each singer would preface an individual selection with a serving of music history, humor, and charm.

There is no question these popular gentlemen love what they are doing — touring, recording, and singing. Every piece is approached with evident joy, and this infectious enthusiasm may well be the secret to their very successful long run. There is hardly a shortage these days of very good a cappella groups; many are much in vogue on both sides of the Atlantic. But this long-lasting ensemble offers not only a perfect blend of voices, but charisma galore. And most of its members are significant soloists — there were no weak links.

For this listener, the musical highlight was the group’s inventive use of harmony, which refreshed old favorites and invigorated new songs The most beautiful harmonies could be heard in composer Steven Paulus’s “The Road Home,” part of a selection of home-related songs. A running joke during the concert was how frequently we were reminded that Chanticleer had a brand-new CD out, On a Clear Day. Joking aside, it’s most probably well worth having.

— Susan Miron

Mercury Orchestra is made up of seriously committed players, and they did a phenomenal job of bringing Mahler’s death-haunted work to life.

Channing Yu conducting the Mercury Orchestra. Photo: Robert Torres/Mercury Orchestra

One of the best concerts this summer took place recently at Sanders Theatre in Cambridge. The experience was surprising because I attended with low expectations. I wanted to hear the Mahler Ninth live, even if it was being performed by an all-volunteer orchestra. It turns out that I had missed the consistently rave reviews for the Mercury Orchestra. The ensemble appeared on the Boston scene 15 years ago under the gifted conductor Channing Yu. Their mission is to gather excellent freelancers to play major symphonic pieces over the summer as well as to educate new audiences about the rich traditions of classical music. During the summer, the troupe has two rehearsals a week and two concerts. All the players are volunteers, and they are darn good. Channing Yu is amazing. He has been an award-winning pianist, a professional violinist, and a lyric baritone. The impressively diverse audience at the performance I attended included 100 well-behaved high schoolers.

A challenging meditation on mortality, the Mahler Ninth has acted as a Rorschach test for conductors, commentators, and audiences. It hardly qualifies as easy listening; still, the two long outer movements are deeply emotional — a complex mix of deep pain, grief, and serenity. Mahler’s tempo markings are revelatory: Movement 2: ländler, rather clumsy and very rough. Movement 3: very defiant. Movement 4: slowly and cautiously. Conductor Bruno Walter deftly described the last movement as “a peaceful farewell. At the conclusion, the clouds dissolve in the blue of heaven.”

There is plenty of praise to go around. The program notes by Roger Hecht were superb. I sat near the harps and had the time of my life watching and listening to the wonderful first harp, Angelina Savoia, who played her huge part in the first and final movements with grace and elegant precision. The strings were very good. I especially enjoyed the bubbly vibrancy of the second violin section. The winds and brass were outstanding, particularly the horns and bassoons. Mercury Orchestra is made up of seriously committed players, and they did a phenomenal job of bringing Mahler’s death-haunted work to life.

— Susan Miron

If one needed more evidence that this period ensemble can play music from any era, I suppose this is it.

Not every 100th birthday party gets started seven years early. But that’s sort of what happened with Les Siècles’ “new” recording of chamber music by this year’s notable birthday boy, György Ligeti. All three pieces on this shortish release — the Six Bagatelles, Chamber Concerto, and 10 Pieces for Woodwind Quintet — were recorded back in 2016.

Not every 100th birthday party gets started seven years early. But that’s sort of what happened with Les Siècles’ “new” recording of chamber music by this year’s notable birthday boy, György Ligeti. All three pieces on this shortish release — the Six Bagatelles, Chamber Concerto, and 10 Pieces for Woodwind Quintet — were recorded back in 2016.

No matter: they’re played with Les Siècles’ typical brilliance. To be sure, if one needed more evidence that this period ensemble can play music from any era, I suppose this is it.

At any rate, in the Bagatelles, which is a piece for woodwinds adapted from Ligeti’s 1953 piano collection Musica ricercata, we’ve got no shortage of spirit and character. The opening Allegro con spirito is dry and droll as ever; the Rubato sings plangently; and the Presto ruvido’s taut and bright.

The 10 Pieces date from 1968 and inhabit a completely different sonic world. And yet … the music’s aphoristic gestures (see the clarinet solos in the Prestissimo minaccioso e burlesco) and keening moments clearly hail from a related pen. All of it is played here with the same incisive energy and attention to coloristic detail that marked Les Siècles’ enlivening reading of the earlier work.

In between comes the obsessively virtuosic Chamber Concerto in a performance that ranks right up there with the best on disc (in my book that’s the Schönberg Ensemble’s with Reinbert de Leeuw). Yes, the earlier rendering is a bit more biting and, especially in the third movement, playful.

But this one boasts a finale that’s marvelously shaped, not to mention winning linear clarity throughout. What’s more, conductor François-Xavier Roth teases out melodic lines in this Concerto that are clear enough on paper but rarely enough emerge as such in performance. Taken together, then, this is something special.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

One could hardly ask for a more devoted advocate for this fare than pianist Michelle Cann. She knows this music deeply and clearly loves it.

The word “revival” has artistic as well as religious applications. On Michelle Cann’s eponymous album, the term seems to be applied both ways.

On the one hand, here Cann is advocating for the music of Florence Price and Margaret Bonds. The two were personally close: Bonds studied with Price and premiered her teacher’s Fantasie nègre No. 1 in 1930. That piece (along with Fantasie’s Nos. 2 and 4) are here. So is Price’s sprawling Piano Sonata in E minor and Bonds’s Spiritual Suite.

At the same time, there’s a strongly devotional aspect to much of this music. Sometimes the spiritual (or Spiritual) connection is explicit: Bonds’s virtuosic Suite adapts three of them (most strikingly “Wade in the Water”) as does, in the first Fantasie, Price (she utilized “Sinners, Please Don’t Let This Harvest Pass”).

More often with Price, though, it’s a syntactical thing: the cadences, phrasings, and techniques of Black sacred music informed her style. In these pieces, that connection is utterly compelling.

The Sonata, for instance, hasn’t got a dry moment: it’s shapely, reflective, and fluent, a refreshing antidote to the peripatetic meanderings of her symphonic output. Much the same goes for the Fantasies, with their soulful contrasts of mood and tone, and ingratiatingly idiomatic keyboard writing.

One could hardly ask for a more devoted advocate for this fare than Cann. She knows this music deeply and clearly loves it. Voicings are ever on-point, tempos flow, and balances emerge pristinely.

Indeed, not once in these busy keyboard textures — and more than a few of them are fully worthy of Rachmaninoff for density and harmonic interest — is the line lost or does the music’s overarching goal get muddied. Rather, Cann’s is dynamic, sensitive pianism, the ideal vehicle for this music, which truly and invigoratingly comes to life in her hands.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Visual Art

Given the show’s excessive amount of verbiage, you wish that the art had been left to speak for itself.

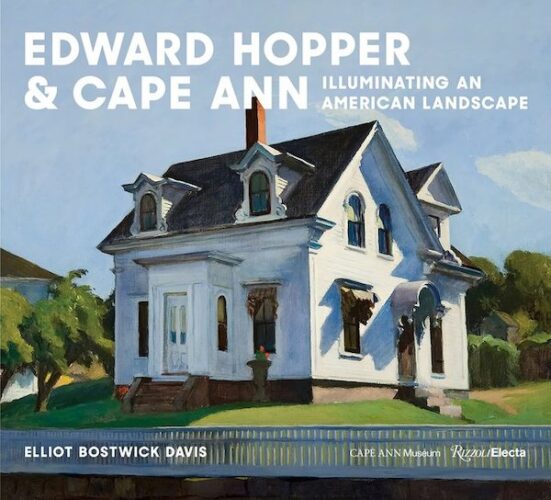

What made the latest Edward Hopper blockbuster at the Cape Ann Museum a meh-xibition? There are a few reasons.

I know that Hopper’s a semi-hometown hero and, as a Gloucester resident, I got a kick out of looking at a Hopper canvas and saying, “That’s the street where I park my car.” But the curatorial emphasis on his Gloucester connection, heavily underlined by the copious signage concerning his comings and goings, is over the top. Given the show’s excessive amount of verbiage, you wish that art had been left to speak for itself.

And that argument does not hold when the art is not convincing. A number of charcoal or pencil sketches and studies are included here, and they are not particularly instructive or compelling. There are only a handful of large oil canvases and many watercolors. The oils are stunning and sustain the mystique of the Hopper we know through Automat, Hotel Room, and, of course, Nighthawks. Some of the watercolors reflect Hopper’s unusual and often surprising framing approach — aerial street views, off angle views of yards, fences, or houses. And, of course, many of them are very skillfully rendered. But if one evaluates the watercolors on their own terms — without applying a retroactive interpretation that comes of knowing the later Hopper — most of these watercolors don’t have the gravitas and mystique imputed to them.

And then there’s the way the exhibition is lit. To evaluate the quality of the art, it is necessary to be able to see it. I know that the request for lower level of lighting was imposed by those who lent the artwork. But one person’s “hushed” is another person’s indiscernible.

I like this museum and I’m there a lot. They’re doing an efficient job of managing the large crowds, but the scale of the Hopper show was a miscalculation. More was less. The same curatorial end could have been accomplished with a more modest exhibition, which would probably have supplied a more satisfying aesthetic experience.

— Steve Provizer

Books

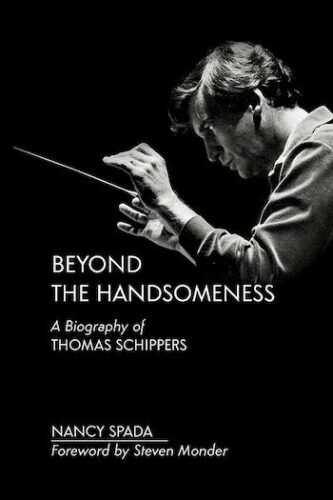

Beyond the Handsomeness is a worthy memorial to a major performing artist who belonged to America and to the whole musical world. Also a reminder of what we all lost.

The commercial recordings made by American conductor Thomas Schippers (1930-1977) have been prized by record collectors since they first came out. Fortunately, these were made for major labels and therefore have remained available in rerelease. Readers here may know Schippers’s Carmen (with Regina Resnik), Macbeth (with Birgit Nilsson), Lucia (with Beverly Sills), the premiere recording of Amahl and the Night Visitors, or a vividly rendered disc of orchestral pieces by Samuel Barber.

The commercial recordings made by American conductor Thomas Schippers (1930-1977) have been prized by record collectors since they first came out. Fortunately, these were made for major labels and therefore have remained available in rerelease. Readers here may know Schippers’s Carmen (with Regina Resnik), Macbeth (with Birgit Nilsson), Lucia (with Beverly Sills), the premiere recording of Amahl and the Night Visitors, or a vividly rendered disc of orchestral pieces by Samuel Barber.

What many of us never knew, or no longer remember — because he died so young and so long ago — is that “Tommy,” as friends called him, was once one of the leading conductors in the world. He frequently led the New York Philharmonic and Chicago Symphony Orchestras, and he helped found Gian Carlo Menotti’s “Festival of Two Worlds” in Spoleto (Italy). From 1970 until his death at 47 (from lung cancer), he served as Music Director at the Cincinnati Symphony, forging a strong bond with the orchestra’s players and with the city’s music-loving audience.

True opera mavens, looking beyond the commercial releases mentioned above, cherish Schippers’s pirate recordings, such as Cherubini’s Medea at La Scala, 1961, with Maria Callas. (Not to be confused with Leonard Bernstein’s intense recording, likewise noncommercial, of the same opera, made eight years earlier with the same soprano in the same opera house.) Video excerpts from the 1961 production, which also featured tenor Jon Vickers, can be seen on YouTube.

How extensive and wide-ranging Schippers’s repertory was can be sensed from the discography that ends this new book, Beyond the Handsomeness the first-ever English-language biography of this remarkable musician (available at $34.95, or, as an e-book, at $29; an audiobook version exists, though read by a computerized voice).

The author, Nancy Spada, is a musician and writer who has spent much of her adult life in Italy; her late husband Pietro Spada was a renowned pianist and scholar who spearheaded modern critical editions of works by Clementi and other important composers.

In this book, Spada shares, for the most part indirectly, her own impressions of “Tommy.” Also, impressive: over a number of years she has done an enormous amount of legwork, gathering reviews of Schippers’s performances and interviewing dozens of musicians and theater people who worked with him or knew him well, such as sopranos Martina Arroyo and Jane Marsh, pianist Earl Wild, conductors Carmon DeLeone and Peter Stafford Wilson, composer Ned Rorem, stage designer Tony Walton, and Schippers’s brother Henry and personal assistant Margot Melniker. Steven Monder, the Cincinnati orchestra’s former president and CEO, provides an informative and insightful 12-page foreword.

Spada’s writing is clear and straightforward, and she provides dozens of photos, beautifully reproduced on bright white paper. The book is a worthy memorial to a major performing artist who belonged to America and to the whole musical world. Also a reminder of what we all lost. May more of Schippers’s recordings be made widely available!

— Ralph P. Locke

Popular Music

The Clientele will play their first stateside show since 2017 at Somerville’s Crystal Ballroom on August 9.

The Clientele reliably delivered an LP or EP’s worth of their instantly identifiable material every year or so between 2000 and 2010.

Then, after five years of silence, the 2015 arrival of Alone & Unreal: The Best of The Clientele seemed to indicate that the band had run its course. This made 2017’s Music for the Age of Miracles — about which I wrote, “The band’s dedication to writing the soundtrack of autumn days in all their overcast and colorful glory hasn’t wavered” — an all the more pleasant surprise.

This time, the Alasdair MacLean-led trio (which also includes bassist James Hornsey and drummer Mark Keen) made its fans wait six years for new material, and rewarded their patience with the 19-track, 63-minute I Am Not There Anymore, the reviews of which might literally be the best that the highly acclaimed band has ever gotten.

Most of the songs run the standard pop song length of two to five minutes. However, “Fables of the Silverlink,” is an 8-1/2-minute epic of an opener, “Segue 4 (IV)” runs for 28 seconds, and four tracks that are identified as “Radial B,” Radial C,” “Radial E,” and “Radial H” are brief inclusions that MacLean compares to “the spokes from the center of the wheel” that “change the focus in between songs.”

For an idea of how I’m Not There Anymore differs from previous entries in The Clientele’s catalog, consider these quotes form the bandleader: “What happened with this record was that we bought a computer” and “I’d been listening to On the Corner by Miles Davis.” Moreover, a significant portion of the lyrical content was inspired by MacLean’s memories of his mother, who died in 1997.

While this might (though probably not) make some longtime listeners circumspect, I assure them that they need not worry. Songs like “Blue Over Blue,” “Dying in May,” “Claire’s Not Real,” and “Lady Grey” will have them feeling right at home in the audial atmosphere that only The Clientele can create.

— Blake Maddux

Tagged: 6 sonate a quattro, Adam Ellsworth, Bill-Marx, Blake Maddox, Brown University, Cape Ann Museum, Edward Hopper, Edward Hopper & Cape Ann, Harold-Pinter, Infinite Composition, I’m Not There Anymore, Joseph Losey, Leaf Music, Leo Villarreal, Lindemann Performing Arts Center, Mark Favermann, Mercury Orchestra, Nancy Spada, Nina Simone, Nina Simone: You’ve Got to Learn, Ralph P. Locke, Rossini, Susan Miron, The Clientele, The Servant